The article itself has a number of pictures, graphs, videos, and interactive graphics.

Two kindergartners in Utah told a Latino boy that President Trump would send him back to Mexico, and teenagers in Maine sneered “Ban Muslims” at a classmate wearing a hijab. In Tennessee, a group of middle-schoolers linked arms, imitating the president’s proposed border wall as they refused to let nonwhite students pass. In Ohio, another group of middle-schoolers surrounded a mixed-race sixth-grader and, as she confided to her mother, told the girl: “This is Trump country.”

Since Trump’s rise to the nation’s highest office, his inflammatory language — often condemned as racist and xenophobic — has seeped into schools across America. Many bullies now target other children differently than they used to, with kids as young as 6 mimicking the president’s insults and the cruel way he delivers them.

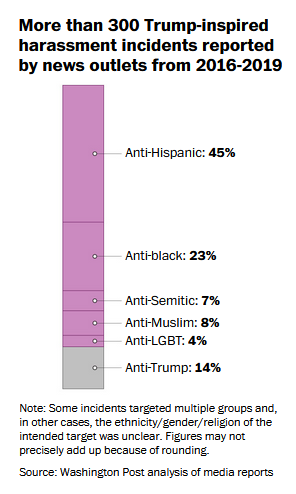

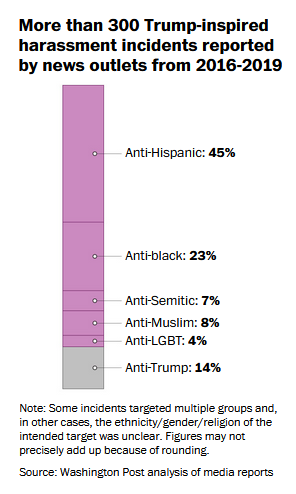

Trump’s words, those chanted by his followers at campaign rallies and even his last name have been wielded by students and school staff members to harass children more than 300 times since the start of 2016, a Washington Post review of 28,000 news stories found. At least three-quarters of the attacks were directed at kids who are Hispanic, black or Muslim, according to the analysis. Students have also been victimized because they support the president — more than 45 times during the same period.

Although many hateful episodes garnered coverage just after the election, The Post found that Trump-connected persecution of children has never stopped. Even without the huge total from November 2016, an average of nearly two incidents per school week have been publicly reported over the past four years. Still, because so much of the bullying never appears in the news, The Post’s figure represents a small fraction of the actual total. It also doesn’t include the thousands of slurs, swastikas and racial epithets that aren’t directly linked to Trump but that the president’s detractors argue his behavior has exacerbated.

“It’s gotten way worse since Trump got elected,” said Ashanty Bonilla, 17, a Mexican American high school junior in Idaho who faced so much ridicule from classmates last year that she transferred. “They hear it. They think it’s okay. The president says it. . . . Why can’t they?”

Asked about Trump’s effect on student behavior, White House press secretary Stephanie Grisham noted that first lady Melania Trump — whose “Be Best” campaign denounces online harassment — had encouraged kids worldwide to treat one another with respect.

“She knows that bullying is a universal problem for children that will be difficult to stop in its entirety,” Grisham wrote in an email, “but Mrs. Trump will continue her work on behalf of the next generation despite the media’s appetite to blame her for actions and situations outside of her control.”

Most schools don’t track the Trump bullying phenomenon, and researchers didn’t ask about it in a federal survey of 6,100 students in 2017, the most recent year with available data. One in five of those children, ages 12 to 18, reported being bullied at school, a rate unchanged since the previous count in 2015.

However, a 2016 online survey of over 10,000 kindergarten through 12th-grade educators by the Southern Poverty Law Center found that more than 2,500 “described specific incidents of bigotry and harassment that can be directly traced to election rhetoric,” although the overwhelming majority never made the news. In 476 cases, offenders used the phrase “build the wall.” In 672, they mentioned deportation.

For Cielo Castor, who is Mexican American, the experience at Kamiakin High in Kennewick, Wash., was searing. The day after the election, a friend told Cielo, then a sophomore, that he was glad Trump won because Mexicans were stealing American jobs. A year later, when the president was mentioned during her American literature course, she said she didn’t support him and a classmate who did refused to sit next to her.

“‘I don’t want to be around her,’ ” Cielo recalled him announcing as he opted for the floor instead.

Then, on “America night” at a football game in October 2018 during Cielo’s senior year, schoolmates in the student section unfurled a “Make America Great Again” flag. Led by the boy who wouldn’t sit beside Cielo, the teenagers began to chant: “Build — the — wall!”

Horrified, she confronted the instigator.

“You can’t be doing that,” Cielo told him.

He ignored her, she recalled, and the teenagers around him booed her. A cheerleading coach was the lone adult who tried to make them stop.

After a photo of the teenagers with the flag appeared on social media, news about what had happened infuriated many of the school’s Latinos, who made up about a quarter of the 1,700-member student body. Cielo, then 17, hoped school officials would address the tension. When they didn’t, she attended that Wednesday’s school board meeting.

“I don’t feel cared for,” she told the members, crying.

A day later, the superintendent consoled her and the principal asked how he could help, recalled Cielo, now a college freshman. Afterward, school staff members addressed every class, but Hispanic students were still so angry that they organized a walkout.

Some students heckled the protesters, waving MAGA caps at them. At the end of the day, Cielo left the school with a white friend who’d attended the protest; they passed an underclassman she didn’t know.

“Look,” the boy said, “it’s one of those f—ing Mexicans.”

She heard that school administrators — who declined to be interviewed for this article — suspended the teenager who had led the chant, but she doubts he has changed.

Reached on Instagram, the teenager refused to talk about what happened, writing in a message that he didn’t want to discuss the incident “because it is in the past and everyone has moved on from it.” At the end, he added a sign-off: “Trump 2020.”

Just as the president has repeatedly targeted Latinos, so, too, have school bullies. Of the incidents The Post tallied, half targeted Hispanics.

In one of the most extreme cases of abuse, a 13-year-old in New Jersey told a Mexican American schoolmate, who was 12, that “all Mexicans should go back behind the wall.” A day later, on June 19, 2019, the 13-year-old assaulted the boy and his mother, Beronica Ruiz, punching him and beating her unconscious, said the family’s attorney, Daniel Santiago. He wonders to what extent Trump’s repeated vilification of certain minorities played a role.

“When the president goes on TV and is saying things like Mexicans are rapists, Mexicans are criminals — these children don’t have the cognitive ability to say, ‘He’s just playing the role of a politician,’ ” Santiago argued. “The language that he’s using matters.”

Ruiz’s son, who is now seeing a therapist, continues to endure nightmares from an experience that may take years to overcome. But experts say that discriminatory language can, on its own, harm children, especially those of color who may already feel marginalized.

“It causes grave damage, as much physical as psychological,” said Elsa Barajas, who has counseled more than 1,000 children in her job at the Los Angeles Department of Mental Health.

As a result, she has seen Hispanic students suffer from sleeplessness, lose interest in school, and experience inexplicable stomach pain and headaches.

For Ashanty Bonilla, the damage began with the response to a single tweet she shared 10 months ago.

“Unpopular opinion,” Ashanty, then 16 and a sophomore at Lewiston High School in rural Idaho, wrote on April 9. “People who support Trump and go to Mexico for vacation really piss me off. Sorry not sorry.”

A schoolmate, who is white, took a screen shot of her tweet and posted it to Snapchat, along with a Confederate flag.

“Unpopular opinion but: people that are from Mexico and come in to America illegally or at all really piss me off,” he added in a message that spread rapidly among students.

The next morning, as Ashanty arrived at school, half a dozen boys, including the one who had written the message, stood nearby.

“You’re illegal. Go back to Mexico,” she heard one of them say. “F— Mexicans.”

Ashanty, shaken but silent, walked past as a friend yelled at the boys to shut up.

In a 33,000-person town that is 94 percent white, Ashanty, whose father is half-black and whose mother is Mexican American, had always worked to fit in. She attended every football game and won a school spirit award as a freshman. She straightened her hair and dyed it blond, hoping to look more like her friends.

She had known those boys who’d heckled her since they were little. For her 15th birthday the year before, some had danced at her quinceañera.

A friend drove her off campus for lunch, but when they pulled back into the parking lot, Ashanty spotted people standing around her car. A rope had been tied from the back of the Honda Pilot to a pickup truck.

“Republican Trump 2020,” someone had written in the dust on her back window.

Hands trembling, Ashanty tried to untie the rope but couldn’t. She heard the laughing, sensed the cellphone cameras pointed at her. She began to weep.

Lewiston’s principal, Kevin Driskill, said he and his staff met with the boys they knew were involved, making clear that “we have zero tolerance for any kind of actions like that.” The incidents, he suspected, stemmed mostly from ignorance.

“Our lack of diversity probably comes with a lack of understanding,” Driskill said, but he added that he’s encouraged by the school district’s recent creation of a community group — following racist incidents on other campuses — meant to address those issues.

That effort came too late for Ashanty.

Some friends supported her, but others told her the boys were just joking. Don’t ruin their lives.

She seldom attended classes the last month of school. That summer, she started having migraines and panic attacks. In August, amid her spiraling despair, Ashanty swallowed 27 pills from a bottle of antidepressants. A helicopter rushed her to a hospital in Spokane, Wash., 100 miles away.

After that, she began seeing a therapist and, along with the friend who defended her, transferred to another school. Sometimes, she imagines how different life might be had she never written that tweet, but Ashanty tries not to blame herself and has learned to take more pride in her heritage. She just wishes the president understood the harm his words inflict.

Even Trump’s last name has become something of a slur to many children of color, whether they’ve heard it shouted at them in hallways or, in her case, seen it written on the back window of a car.

“It means,” she said, “you don’t belong.”

Three weeks into the 2018-19 school year, Miracle Slover’s English teacher, she alleges, ordered black and Hispanic students to sit in the back of the classroom at their Fort Worth high school.

At the time, Miracle was a junior. Georgia Clark, her teacher at Amon Carter-Riverside, often brought up Trump, Miracle said. He was a good person, she told the class, because he wanted to build a wall.

“Every day was something new with immigration,” said Miracle, now 18, who has a black mother and a mixed-race father. “That Trump needs to take [immigrants] away. They do drugs, they bring drugs over here. They cause violence.”

Some students tried to film Clark, and others complained to administrators, but none of it made a difference, Miracle said. Clark, an employee of the Fort Worth system since 1998, kept talking.

Clark, who denies the teenager’s allegations, is one of more than 30 educators across the country accused of using the president’s name or rhetoric to harass students since he announced his candidacy, the Post analysis found.

In Clark’s class, Miracle stayed quiet until late spring 2019. That day, she walked in wearing her hair “puffy,” split into two high buns.

Clark, she said, told her it looked “nappy, like Marge off ‘The Simpsons.’ ” Unable to smother an angry reply, Miracle landed in the principal’s office. An administrator asked her to write a witness statement, and in it, she finally let go, scrawling her frustration across seven pages.

“I just got tired of it,” she said. “I wrote a ton.”

Still, Miracle said, school officials took no action until six weeks later, when Clark, 69, tweeted at Trump — in what she thought were private messages — requesting help deporting undocumented immigrants in Fort Worth schools. The posts went viral, drawing national condemnation. Clark was fired.

Not always, though, are offenders removed from the classroom.

The day after the 2016 election, Donnie Jones Jr.’s daughter was walking down a hallway at her Florida high school when, she says, a teacher warned her and two friends — all sophomores, all black — that Trump would “send you back to Africa.”

The district suspended the teacher for three days and transferred him to another school.

Just a few days later in California, a physical education teacher told a student that he would be deported under Trump. Two years ago in Maine, a substitute teacher referenced the president’s wall and promised a Lebanese American student, “You’re getting kicked out of my country.” More than a year later in Texas, a school employee flashed a coin bearing the word “ICE” at a Hispanic student. “Trump,” he said, “is working on a law where he can deport you.”

Sometimes, Jones said, he doesn’t recognize America.

“People now will say stuff that a couple of years ago they would not dare say,” Jones argued. He fears what his two youngest children, ages 11 and 9, might hear in their school hallways, especially if Trump is reelected.

Now a senior, Miracle doesn’t regret what she wrote about Clark. Although the furor that followed forced Miracle to switch schools and quit her beloved dance team, she would do it again, she said. Clark’s punishment, her public disgrace, was worth it.

About a week before Miracle’s 18th birthday, her mother checked Facebook to find a flurry of notifications. Friends were messaging to say that Clark had appealed her firing, and that the Texas education commissioner had intervened.

Reluctant to spoil the birthday, Jowona Powell waited several days to tell her daughter, who doesn’t use social media.

Citing a minor misstep in the school board’s firing process, the commissioner had ordered Carter-Riverside to pay Clark one year’s salary — or give the former teacher her job back.

Jordyn Covington stood when she heard the jeers.

“Monkeys!” “You don’t belong here.” “Go back to where you came from!”

From atop the bleachers that day in October, Jordyn, 15, could see her Piper High School volleyball teammates on the court in tears. The sobbing varsity players were all black, all from Kansas City, Kan., like her.

Who was yelling? Jordyn wondered.

She peered at the students in the opposing section. Most of them were white.

“It was just sad,” said Jordyn, who plays for Piper’s junior varsity team. “And why? Why did it have to happen to us? We weren’t doing anything. We were simply playing volleyball.”

Go back? To where? Jordyn, her friends and Piper’s nine black players were all born in the United States. “Just like everyone else,” Jordyn said. “Just like white people.”

The game, played at an overwhelmingly white rural high school, came three months after Trump tweeted that four minority congresswomen should “go back” to the “totally broken and crime infested places from which they came.”

It was Jordyn’s first experience with racism, she said. But it was not the first time that fans at a school sports game had used the president to target students of color.

The Post found that players, parents or fans have used his name or words in at least 48 publicly reported cases, hurling hateful slogans at students competing in elementary, middle and high school games in 26 states.

The venom has been shouted on football gridirons and soccer fields, on basketball and volleyball courts. Nearly 90 percent of incidents identified by The Post targeted players and fans of color, or teams fielded by schools with large minority populations. More than half focused on Hispanics.

In one of the earliest examples, students at a Wisconsin high school soccer game in April 2016 chanted “Trump, build a wall!” at black and Hispanic players. A few months later, students at a high school basketball game in Missouri turned their backs and hoisted a Trump/Pence campaign sign as the majority-black opposing team walked onto the court. In 2017, two high school girls in Alabama showed up at a football game pep rally with a sign reading “Put the Panic back in Hispanic” and a “Trump Make America Great Again” banner.

In late 2017, two radio hosts announcing a high school basketball game in Iowa were caught on a hot mic describing Hispanic players as “español people.” “As Trump would say,” one broadcaster suggested, “go back where they came from.”

Both announcers were fired. After the volleyball incident in Kansas, though, the fallout was more muted. The opposing school district, Baldwin City, commissioned an investigation and subsequently asserted that there was “no evidence” of racist jeers. Administrators from Piper’s school system dismissed that claim and countered with a statement supporting their students.

An hour after the game, Jordyn fought to keep her eyes dry as she boarded the team bus home. When white players insisted that everything would be okay, she slipped in ear buds and selected “my mood playlist,” a collection of somber nighttime songs. She wiped her cheeks.

Jordyn had long ago concluded that Trump didn’t want her — or “anyone who is just not white” — in the United States. But hearing other students shout it was different.

Days later, her English teacher assigned an essay asking about “what’s right and what’s wrong.” At first, Jordyn thought she might write about the challenges transgender people face. Then she had another idea.

“The students were making fun of us because we were different, like our hair and skin tone,” Jordyn wrote. “How are you gonna be mad at me and my friends for being black. . . . I love myself and so should all of you.”

She read it aloud to the class. She finished, then looked up. Everyone began to applaud.

It’s not just young Trump supporters who torment classmates because of who they are or what they believe. As one boy in North Carolina has come to understand, kids who oppose the president — kids like him — can be just as vicious.

By Gavin Trump’s estimation, nearly everyone at his middle school in Chapel Hill comes from a Democratic family. So when the kids insist on calling him by his last name — even after he demands that they stop — the 13-year-old knows they want to provoke him, by trying to link the boy to the president they despise.

In fifth grade, classmates would ask if he was related to the president, knowing he wasn’t. They would insinuate that Gavin agreed with the president on immigration and other polarizing issues.

“They saw my last name as Trump, and we all hate Trump, so it was like, ‘We all hate you,’ ” he said. “I was like, ‘Why are you teasing me? I have no relationship to Trump at all. We just ended up with the same last name.’ ”

Beyond kids like Gavin, the Post analysis also identified dozens of children across the country who were bullied, or even assaulted, because of their allegiance to the president.

School staff members in at least 18 states, from Washington to West Virginia, have picked on students for wearing Trump gear or voicing support for him. Among teenagers, the confrontations have at times turned physical. A high school student in Northern California said that after she celebrated the 2016 election results on social media, a classmate accused her of hating Mexicans and attacked her, leaving the girl with a bloodied nose. Last February, a teenager at an Oklahoma high school was caught on video ripping a Trump sign out of a student’s hands and knocking a red MAGA cap off his head.

And in the nation’s capital — where only 4 percent of voters cast ballots for Trump in 2016 — an outspoken conservative teenager said she had to leave her prestigious public school because she felt threatened.

In a YouTube video, Jayne Zirkle, a high school senior, said that the trouble started when classmates at the School Without Walls discovered an online photo of her campaigning for Trump. She said students circulated the photo, harassed her online and called her a white supremacist.

A D.C. school system official said they investigated the allegations and allowed Jayne to study from home to ensure she felt safe.

“A lot of people who I thought were my best friends just all of a sudden totally turned their backs on me,” Jayne said. “People wouldn’t even look at me or talk to me.”

For Gavin, the teasing began in fourth grade, soon after Trump announced his candidacy.

After more than a year of schoolyard taunts, Gavin decided to go by his mother’s last name, Mather, when he started middle school. The teenager has been proactive, requesting that teachers call him by the new name, but it gets trickier, and more stressful, when substitutes fill in. He didn’t legally change his last name, so “Trump” still appears on the roster.

The teasing has subsided, but the switch wasn’t easy. Gavin likes his real last name and feared that changing it would hurt his father’s feelings. His dad understood, but for Gavin, the guilt remains.

“This is my name,” he said. “And I am abandoning my name.”

Maritza Avalos knows what’s coming. It’s 2020. The next presidential election is nine months away. She remembers what happened during the last one, when she was just 11.

“Pack your bags,” kids told her. “You get a free trip to Mexico.”

She’s now a freshman at Kamiakin High, the same Washington state school where her older sister, Cielo, confronted the teenagers who chanted “Build the wall” at a football game in late 2018. Maritza, 14, assumes the taunts that accompanied Trump’s last campaign will intensify with this one, too.

“I try not to think about it,” she said, but for educators nationwide, the ongoing threat of politically charged harassment has been impossible to ignore.

In response, schools have canceled mock elections, banned political gear, trained teachers, increased security, formed student-led mediation groups and created committees to develop anti-discrimination policies.

In California, the staff at Riverside Polytechnic High School has been preparing for this year’s presidential election since the day after the last one. On Nov. 9, 2016, counselors held a workshop in the library for students to share their feelings. Trump supporters feared they would be singled out for their beliefs, while girls who had heard the president brag about sexually assaulting women worried that boys would be emboldened to do the same to them.

“We treated it almost like a crisis,” said Yuri Nava, a counselor who has since helped expand a student club devoted to improving the school’s culture and climate.

Riverside, which is 60 percent Hispanic, also offers three courses — African American, Chicano and ethnic studies — meant to help students better understand one another, Nava said. And instead of punishing students when they use race or politics to bully, counselors first try to bring them together with their victims to talk through what happened. Often, they leave as friends.

In Gambrills, Md., Arundel High School has taken a similar approach. Even before a student was caught scribbling the n-word in his notebook in early 2017, Gina Davenport, the principal, worried about the effect of the election’s rhetoric. At the school, where about half of the 2,200 students are minorities, she heard their concerns every day.

But the racist slur, discovered the same month as Trump’s inauguration, led to a concrete response.

A “Global Community Citizenship” class, now mandatory for all freshmen in the district, pushes students to explore their differences.

A recent lesson delved into Trump’s use of Twitter.

“The focus wasn’t Donald Trump, the focus was listening: How do we convey our ideas in order for someone to listen?” Davenport said. “We teach that we can disagree with each other without walking away being enemies — which we don’t see play out in the press, or in today’s political debates.”

Since the class debuted in fall 2017, disciplinary referrals for disruption and disrespect have decreased by 25 percent each school year, Davenport said. Membership in the school’s speech and debate team has doubled.

The course has eased Davenport’s anxiety heading into the next election. She doesn’t expect an uptick in racist bullying.

“Civil conversation,” she said. “The kids know what that means now.”

Many schools haven’t made such progress, and on those campuses, students are bracing for more abuse.

Maritza’s sister, Cielo, told her to stand up for herself if classmates use Trump’s words to harass her, but Maritza is quieter than her sibling. The freshman doesn’t like confrontation.

She knows, though, that eventually someone will say something — about the wall, maybe, or about how kids who look like her don’t belong in this country — and when that day comes, the girl hopes that she’ll be strong.