Two months before the presidential election, the US intelligence agencies are under increasing pressure from the Trump administration to provide only the information it wants to hear.

After installing loyalist John Ratcliffe at the pinnacle of the intelligence community, the administration is seeking to limit congressional oversight, and has removed a veteran official from a sensitive national security role in the justice department

One former senior intelligence officer has suggested Donald Trump is seeking to create the very thing he was repeatedly complained about: a “deep state”. Another official has compared it to the intelligence fiasco that preceded the 2003 Iraq invasion.

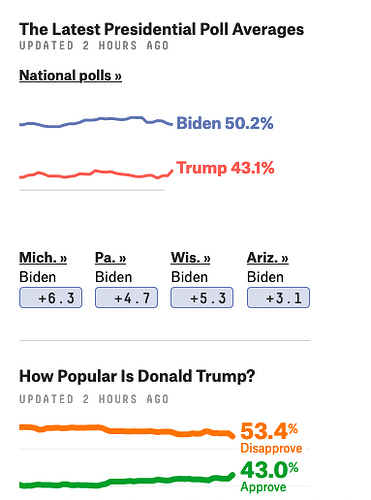

The intense focus of the current struggle is the covert Russian role in the election campaign. The intelligence community has assessed that Moscow is taking an active role, as it did in 2016, to damage Joe Biden and boost Trump, largely through spreading disinformation. But administration officials have sought to stop public discussion of such interference.

ABC News reported this week that an aide to the homeland security secretary, Chad Wolf, blocked a bulletin in July warning about Russian efforts to create doubts about Joe Biden’s mental health.

Ratcliffe, the new director of national intelligence (DNI), informed Congress at the end of last week that his office would no longer provide in-person briefings on election security, but would instead deliver written reports that could not be subjected to cross-examination by sceptical legislators.

He justified his action by accusing Congress of leaking classified material but did not explain why the same risk did not apply to written reports. John McLaughlin, former deputy CIA director, said the fears of leaks should not outweigh the need for transparency.

“Frankly, having briefed the Congress many times, it’s possible to talk about sensitive things without giving away sources and methods,” McLaughlin told the Guardian.

“In my view the American voter needs to know as much about this as can be revealed. They need to know if someone is attempting to influence their vote or manipulate them.”

Ratcliffe’s predecessor as acting DNI, Richard Grenell, another highly partisan figure, had sought to consolidate responsibility for election security under that office, taking the highly charged issue out of the hands of career intelligence professionals.

And on Monday it emerged that the attorney general, William Barr, had abruptly removed a veteran official running the law and policy office in the justice department’s national security division.

The official, Brad Wiegmann, was a widely respected career professional, part of whose job was to advise on public disclosure of evidence of election interference. He was replaced by a much younger prosecutor, Kellen Dwyer, a conservative cyber-security specialist with very limited national security experience.

Katrina Mulligan, a former national security official who helped draft the policy by which the law and policy office could raise the alarm on meddling, said: “It remains the only avenue the [justice department] has to disclose foreign interference in the absence of criminal charges.

“As you can imagine, when it comes to foreign interference we may have things going on that the public should know, and we don’t want to wait to have all our ducks in a row for an indictment, before we disclose that to the public,” Mulligan argued.

Is China really the biggest meddler?

As more voices on the issue have been muted, senior Trump officials have been putting out a different message on election interference – that it is China, not Russia, that is the biggest meddler.

“It simply isn’t true that somehow Russia is a greater national security threat than China,” Ratcliffe told Fox News. “China is the greatest threat that we face.”

On Wednesday evening, Barr echoed the claim. “I believe it’s China,” he told CNN, “because I’ve seen the intelligence, that’s what I’ve concluded.”

He would not say who China was backing, but he did not need to. In early August, William Evanina, director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, issued a statement in which he said Russia and China were backing different sides in the election.

“Russia is using a range of measures to primarily denigrate former vice-president Biden,” Evanina said, adding: “We assess that China prefers that President Trump – whom Beijing sees as unpredictable – does not win re-election.”

He gave details of concrete actions that Moscow was taking to damage Biden but was much more vague about Beijing, saying it was “expanding its influence efforts ahead of November 2020 to shape the policy environment” to “deflect and counter criticism of China”.

Democrats and intelligence professionals have complained a false equivalence is being made between the two threats when it comes to direct election interference.

“The documentary evidence on Russia is massive and the documentary evidence – in public at least – on China is minuscule,” McLaughlin said.

John Sipher, a CIA veteran who once ran the agency’s Russia operations, argued in a New York Times commentary on Tuesday that the pattern of the Trump administration’s actions “smacks of the very thing that Mr Trump has used to stoke outrage in his followers – the formation of a politicised national security apparatus that can serve as a personal weapon for the president. A ‘deep state’.”

David Rohde, journalist and author of a book published in April on the issue – In Deep: The FBI, the CIA, and the Truth about America’s “Deep State” – agreed with Sipher’s assessment.

“If a ‘deep state’ is a group of officials who secretly wield government power with little accountability or transparency, Trump and his loyalists increasingly fit that definition,” Rohde said. “Under the guise of stopping a ‘coup’ that does not exist, Trump is politicising the intelligence community and the justice department and using them to boost his re-election effort.”

The battle over intelligence is set to intensify as the election approaches. Barr has picked a prosecutor, John Durham, to investigate the FBI and special counsellor investigators who looked into Russian interference in the 2016 election. The attorney general has said he would not observe normal protocol and wait until after the election to publish Durham’s findings, or at least a version of those findings, with the likely aim of creating the impression that Trump was the victim of a conspiracy to undermine his presidency.

“The Durham investigation presents the opportunity for bad actors to make a lot of mischief, but the lack of clarity makes it difficult for observers to criticise,” said Susan Hennessey, a former National Security Agency attorney.

She added that the Trump tactics in manipulating US intelligence represented a historic threat, potentially overshadowing the fiasco that led to the 2003 Iraq invasion.

“What we are seeing now is, in some respects, even worse than the intelligence failures surrounding weapons of mass destruction,” said Hennessey, now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and executive editor of the Lawfare blog. “Iraq was obviously immensely consequential and illustrates why it is imperative to guard against even subtle political influence in intelligence reporting. But the politicisation here is brazen and explicitly partisan in nature.

“It’s all these little things and so it’s often hard to pin down the precise place where the line has been crossed,” she added. “Lots of lines have been crossed. At this point, the cumulative picture of where we are at is not that there is a risk of politicisation of intelligence, but that we’ve already crossed the Rubicon.”