Unfortunate news…last seen at the Tulsa MAGA Rally, not wearing a mask.

Going on today NOW on CSpan - July 31 7AM PST

Irregularities In COVID Reporting Contract Award Process Raises New Questions

An NPR investigation has found irregularities in the process by which the Trump administration awarded a multi-million dollar contract to a Pittsburgh company to collect key data about COVID-19 from the country’s hospitals.

The contract is at the center of a controversy over the administration’s decision to move that data reporting function from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — which has tracked infection information for a range of illnesses for years — to the Department of Health and Human Services.

TeleTracking Technologies, the company that won the contract, has traditionally focused on creating software for hospitals to track patient status. And there are questions about how it came to be responsible for gathering data in the midst of a pandemic.

Among the findings of the NPR investigation:

The Department of Health and Human Services initially characterized the contract with TeleTracking as a no-bid contract. When asked about that, HHS said there was a "coding error" and that the contract was actually competitively bid. The process by which HHS awarded the contract is normally used for innovative scientific research, not the building of government databases. HHS had directly phoned the company about the contract, according to a company spokesperson. TeleTracking CEO Michael Zamagias had links to the New York real estate world — and in particular, a firm that financed billions of dollars in projects with the Trump Organization.An abrupt change during the pandemic

When the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees the CDC, sent out a directive to the nation’s hospitals in April announcing it would be using TeleTracking as an option to collect COVID data, Carrie Kroll didn’t give it a second thought.

It just seemed like one more form hospitals might need to fill out.

Kroll is with the Texas Hospital Association, and balked only after the HHS suddenly announced in July that hospitals could no longer report COVID data through the CDC, but would instead be required to do so through the HHS-TeleTracking system or their state health departments.

This is the sort of data that has been closely watched since the outbreak of the pandemic: from beds, to personal protective equipment (PPE), to detailed demographic information on suspected and confirmed COVID patients.

“Up until the switch, we were reporting about 70 elements and we’re now at 129,” Kroll said, scrolling through a five-page list of the information now required. “I mean, clearly we’re in the middle of a pandemic, right? I mean this isn’t the type of stuff you try to do in the middle of a pandemic.”

Hospitals were only given days to start sending all this information to TeleTracking. The HHS explained the sudden change by claiming the new database would streamline information gathering and help in the allocation of therapeutic pharmaceuticals like remdesivir.

But thousands of hospitals had used the CDC system for years to report infection control data. So it raised questions: Why the change? Why now?

The CDC has been tracking these numbers for some 15 years. And while its system isn’t perfect — it requires all the information to be entered manually, for example — it is unclear why the government, already underwater with the spread of COVID, didn’t decide instead to tinker with the existing system.

Robert Redfield, the CDC’s director, said the reason HHS chose TeleTracking was because it provided “rapid ways to update the type of data that we’re collecting” and that it “reduces the reporting burden,” none of which, given the duplication of Kroll’s experience around the country, seems to be happening.

The TeleTracking software, for example, requires all the data to be keyed in manually, just like the CDC once did.

An HHS spokesperson said that the COVID response required that they move quickly to implement a new system, “even when more time might be desired. We acknowledge that hospitals were not given significant lead time to prepare for these changes.”

TeleTracking’s ties to Trump Organization financiers

The CEO of the company, Michael Zamagias, came from the real estate sector. He founded Zamagias Properties, a real estate investment and development company, in Pittsburgh, Pa., in 1987.

The company went on to develop iconic office buildings, shopping centers and malls in Pittsburgh and Virginia, and its success helped Zamagias become a fixture outside Pittsburgh and, in particular, in the New York real estate scene.

Zamagias is a longtime Republican donor and community philanthropist, giving generously to Pittsburgh schools and youth programs.

One of the young people who came to Zamagias for advice and counsel was a New Yorker named Neal Cooper, though he was hardly new to business or real estate. Zamagias became the young Cooper’s mentor. He gave Cooper an internship.

Neal’s father, Howard, was the named partner in a Manhattan company called Cooper-Horowitz, one of the largest privately held real estate debt and equity firms in the country.

“Cooper did business with Michael in the late 1980s,” Neal Cooper told NPR, referring to his dad’s company. “I don’t know if we ever did big deals with him, but we ran in the same circles. I learned a lot from Michael. He was always one or two steps ahead of the next guy.”

Cooper-Horowitz handles debt and equity in all classes of real estate and specializes in the hospitality industry.

And in that vein, it did billions of dollars of work with the Trump Organization on projects like the Trump International Hotel & Tower in Chicago.

“I didn’t handle Trump’s account, but I’ve been in meetings with Trump,” Cooper said. “We did tons of business with him, billions of dollars of business.”

And there are other suggestions of a close relationship between Cooper-Horowitz and the Trumps.

Ivanka Trump has attended a rather famous holiday party the company holds in New York every year. The firm has given to the Trump Foundation. And Richard Horowitz, one of the company’s principals, is credited with helping connect the Trump Organization with Deutsche Bank, the German bank that has financed over $2 billion in Trump projects over the past two decades.

There’s no evidence that these professional relationships are why Zamagias and TeleTracking received the multi-million dollar contract. Through a spokesperson Zamagias said that he hadn’t talked to anyone at Cooper-Horowitz in years, and all his company’s contact with the administration came through HHS.

But congressional investigators are now eager to find out if that relationship somehow played a role.

The White House did not respond to questions about whether it was involved in the awarding of the TeleTracking contract, or whether White House staff had any relationship with Zamagias.

An unusual contracting process leads to multi-million dollar TeleTracking deal

Initially, there was confusion about the way HHS awarded the contract to TeleTracking. Public records originally displayed it as a sole-source contract — essentially a no-bid deal.

But after a Senate inquiry and controversy over the mandatory shift to the TeleTracking system, HHS said that there had been a “coding error” and that it had in fact been awarded after a competitive process.

“The TeleTracking contract was part of a competitive solicitation process and was not sole source,” an HHS spokesperson said. “One of the websites that tracks federal spending contained an error that incorrectly categorized the award as sole source. That coding error is being corrected.”

That competitive process, HHS said, is known as a Broad Agency Announcement.BAAs are essentially call-outs to private industry to provide innovative solutions to general problems in which a simple straightforward solution may not be available — it isn’t meant for something like a government database that replaces an existing CDC function.

A standard government contract would usually lay out a series of specific requirements or specifications. Not so with BAAs. By their very nature, they are less competitive than other types of government contracting processes because they may generate an array of solutions that may not necessarily be comparable.

In a statement, an HHS spokesperson said that the BAA is a “common mechanism… for areas of research interest,” and asserted that the healthcare system capacity tracking system previously used by the CDC was “fraught with challenges.”

HHS has said that six companies bid for the contract but declines to say who they were or release the evaluations that the department would have done before awarding the contract to TeleTracking.

“Federal acquisition regulations and statutes prohibit us from providing information about other submissions,” an HHS spokesperson said. The spokesperson added that the BAA was released in August 2019, and that the agency promoted it on social media, in newsletters, and in emails.

But NPR reached out to more than 20 of TeleTracking’s competitors in the fields of hospital workflow management and infection control data and was unable to find a single company that said it had bid on this contract.

One major company told NPR that it hadn’t even heard about the HHS announcement.

There is another wrinkle here. A spokesperson for Zamagias told NPR that HHS reached out to the company directly — by phone — because it knew the company from its hurricane and disaster preparedness work.

It is unclear when that phone call was made.

Congressional investigators probe HHS and TeleTracking

The whole process by which TeleTracking got the contract strikes Virginia Canter, chief ethics counsel at Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, as out of the ordinary.

It isn’t just the use of the BAA. It is that HHS “now requires 6,000 hospitals to enter this data” in what looks like proprietary software, which the federal government may need to pay for in the future, Canter said the current contract ends in September. The Zamagias spokesperson told NPR that TeleTracking hopes for a contract extension — and that potentially means millions of dollars more in the future.

“We do anticipate needing to continue this contract,” an HHS spokesperson said.

Congress is also looking into irregularities in the contract process and the decision to shift the data gathering from CDC to HHS. Sen. Patty Murray, a prominent Democrat on health care, first raised questions about the HHS contract in early June.

And Rep. James Clyburn, who chairs a congressional subcommittee overseeing the coronavirus crisis, and House Oversight Committee Chairwoman Carolyn Maloney are both demanding answers about what happened.

While the inquiries were originally focused on HHS, Clyburn sent a letter to Zamagias Tuesday asking for information on the contracts, emails and communication exchanged with HHS in a bid to understand how TeleTracking came to land the $10.2 million six-month contract in the middle of a pandemic.

“Your company has previously been awarded a handful of small contracts with the Department of Veteran’s Affairs, but your contract with HHS is nearly twenty times larger than all of your previous federal contracts combined,” Clyburn wrote in his letter to Zamagias.

The congressional underclass erupts in fury after Gohmert gets Covid-19

The men and women who make Capitol Hill run are anxious and angry about the risks they’ve been forced to take amid the pandemic.

The revelation Wednesday that Texas Republican Louie Gohmert, a renegade lawmaker known for stalking the halls of Congress without a mask, tested positive for Covid-19 has unleashed a fusillade of anger on Capitol Hill — a sudden release of built-up tension over how the institution has dealt with the coronavirus pandemic within the confines of its own workplace.

For months, the leaders of Congress have allowed lawmakers to enter the Capitol without being screened for the deadly virus, rejecting an offer from the White House to provide rapid testing while trusting that the thousands who work across the massive complex of offices, meeting rooms and hallways will behave responsibly.

Now, legislative aides, chiefs of staff, press assistants, members of Congress, career workers and maintenance men and women are venting their fury with an institution that does not have uniform rules or masking requirements, does not mandate testing, is run with minimal oversight and must contend with a gaggle of lawmakers who doubt scientists and hold themselves out as experts on everything from disease hygiene to pharmacology.

Congress is often buffeted by waves of popular discontent from voters, but what’s happened in recent days has the makings of a historical anomaly: The backlash is coming from the anonymous staff and members who make the place run day to day but are typically accustomed to being told to know their place and accepting that without complaint.

In a nation on edge — and with workplace culture undergoing a generational shift — Congress is now getting a small taste of the same type of internal turbulence that can rock the leaders of The New York Times over an offending op-ed or superintendents of local school systems whose teachers are worried about whether it’s safe to return to the classroom.

“There is a general fear that saying anything critical of the current office policy — or lack of policy — will lead to retaliation,” said an aide to a Republican lawmaker who had been infected, one of a slew of staffers who spoke to POLITICO about their anxiety working in the Capitol.

Other lawmakers have come down with Covid-19. But in many ways, Gohmert’s diagnosis has become a tipping point for a sprawling complex where hundreds of people stream in and out daily, with little institutional guidance.

Hours after Gohmert tested positive — the second case among GOP lawmakers in three weeks — Speaker Nancy Pelosi swiftly implemented a mask mandate for House office buildings and the chamber itself. House Republican leaders recirculated a memo to stress guidance from the Capitol physician, such as limiting or rotating staff, encouraging masks, and implementing home temperature checks.

“The reporting on this situation has led to other reports suggesting House staff reporting unsafe work conditions,” the GOP memo, obtained by POLITICO reads.

Rep. Rodney Davis of Illinois, the top Republican on the House Administration Committee, also delivered a brief presentation on office safety at a private GOP Conference meeting on Thursday.

“Follow OAP and AOC guidance. Take advantage of supplies and thermometers every office can get at no cost to MRA. And lastly, don’t be stupid and become the news story of the day,” Davis said afterward, recalling his message to his fellow Republicans.

Reporters’ inboxes have exploded with complaints and tales of lax safety measures, careless bosses and a widespread feeling that their health was viewed as expendable.

Many described feeling uncomfortable taking the very kinds of health steps recommended by public health experts, and feeling pressured to report to work in person despite the risks. Multiple aides said it was common to mock those wearing masks, or brush off concerns among staff members with specific health issues.

Others recalled seeing aides avoid taking elevator rides with certain members out of fear of contracting the virus — an almost unheard-of reversal of the usual dynamics of power in a place teeming with ambition and hierarchy.

“Our office has been required to be fully staffed since session resumed at the end of June (including an intern),” a scheduler for a House Republican member said. “While mask use isn’t banned, it’s also not encouraged, and has been derided on several occasions by the [chief of staff] and the member.”

Another aide to a House GOP member told of how staff were allowed to work from home for several days when an office colleague was thought to have been exposed. “Even then,” this person said, “many of my colleagues kept working in the office. We were told to report to work as normal even before the test came back negative because the results were taking too long. I was left feeling guilty for teleworking even though I have an underlying health condition.”

An administrative staffer who often visits multiple offices estimated that mask wearing was “nearly universal in Democratic offices” but was “probably under 50 percent” among Republicans.

Masking has become a “political minefield” that creates awkward encounters on occasion, this person recounted: “[S]ome GOP offices ask why you are wearing a mask, which puts our staff in an awkward position — do you say because of the pandemic and risk the office taking that as a political stand? Do you take it off to make them feel better?”

Staffers with limited recourse

Since the House began voting regularly again this summer, dozens, if not hundreds, of offices have reopened in some capacity, many with a skeleton crew but others — particularly GOP members — that have required nearly the entire staff to return to work in person.

And the return of hundreds of staffers has resurfaced a decades-old problem for the Capitol: More than 25 years after the Congressional Accountability Act passed in an attempt to reform the culture on Capitol Hill, it’s still an often brutal, unforgiving place to work.

Part of the problem is the scattershot human resources system spread across the Capitol complex. There is no centralized HR department — each of the 535 lawmakers and senators is his or her own employer, with their own set of office policies and protocols.

Staffers who may be uncomfortable with what’s happening in an office sometimes have limited recourse. For example, if a staffer is uncomfortable with the mask policies in an office, that person can reach out to the Office of Employee Advocacy — which provides free legal counsel to House staffers — or the Office of Congressional Workplace Rights.

But there isn’t some centralized database tracking staffer complaints or concerns, just like there isn’t a singular database to track potential coronavirus infections among the more than 20,000 workers who inhabit the Capitol complex, thousands of staffers and hundreds of lawmakers.

At least 86 Capitol workers have tested positive for coronavirus, according to a House aide familiar with the data. That includes 25 Architect of the Capitol employees, 28 Capitol police officers and 33 people working on the renovation of the Cannon building. But reporting is voluntary and doesn’t include data for House staffers or lawmakers who have tested positive.

Other aides note that overall, there appear to be relatively few coronavirus cases on Capitol Hill, suggesting many offices are indeed following public health guidelines.

Despite the swift move to mandate masks in the House earlier this week, Democratic aides say it’s unlikely Congress will start requiring testing for members, despite calls by some Republicans to do so. Republicans, those Democratic aides say, aren’t being fully truthful about the logistics of implementing a regular testing regime for hundreds of lawmakers and the Capitol staff and aides who would also need to be tested.

Instead, Democrats think the best solution is to fully enforce current policies, including the new mask mandate. If a member refuses to wear a mask on the House floor or in the connected office buildings and brushes off several warnings to do so, it is much more likely he or she will be escorted from the area until complying, according to Democratic aides familiar with the policy.

On the Senate side, Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has urged people to wear masks, though he remains skeptical about the need to require them. Asked about the idea recently by Judy Woodruff of PBS, he said the Senate had experienced “good compliance” without a mandate. Pressed further, he said, “It appears not to be necessary since everybody seems to be doing it.”

Also, something overlooked in the previous Politico story:

Asked by a Politico reporter for comment, an aide to Congressmember Gohmert wrote, “Thank you for letting our office know Louie tested positive for the Coronavirus.” The aide added: “When you write your story, can you include the fact that Louie requires full staff to be in the office, including three interns, so that ‘we could be an example to America on how to open up safely.’ When probing the office, you might want to ask how often were people berated for wearing masks.”

This means that the staff found out from the reporter, NOT Gohmert!

Dr. Fauci rebutts this Rep Luetkemeyer’s assertion that a study had been done showing Hydroxycloroquine’s does heal patients. Dr. Fauci for the 1000th time tells him it was not a placebo controlled study, and therefore not effective. Oh, and that the patients had been given steroids, which always helps in healing.

Video -

Jared Kushner did help create a national testing plan, but it was going to help blue states so they decided to scrap it…according to this Vanity Fair Article.

Though Kushner’s outsized role has been widely reported, the procurement of Chinese-made test kits is being disclosed here for the first time. So is an even more extraordinary effort that Kushner oversaw: a secret project to devise a comprehensive plan that would have massively ramped up and coordinated testing for COVID-19 at the federal level.

Six months into the pandemic, the United States continues to suffer the worst outbreak of COVID-19 in the developed world. Considerable blame belongs to a federal response that offloaded responsibility for the crucial task of testing to the states. The irony is that, after assembling the team that came up with an aggressive and ambitious national testing plan, Kushner then appears to have decided, for reasons that remain murky, to scrap its proposal. Today, as governors and mayors scramble to stamp out epidemics plaguing their populations, philanthropists at the Rockefeller Foundation are working to fill the void and organize enough testing to bring the nationwide epidemic under control.

Inside the White House, over much of March and early April, Kushner’s handpicked group of young business associates, which included a former college roommate, teamed up with several top experts from the diagnostic-testing industry. Together, they hammered out the outline of a national testing strategy. The group—working night and day, using the encrypted platform WhatsApp—emerged with a detailed plan obtained by Vanity Fair.

Rather than have states fight each other for scarce diagnostic tests and limited lab capacity, the plan would have set up a system of national oversight and coordination to surge supplies, allocate test kits, lift regulatory and contractual roadblocks, and establish a widespread virus surveillance system by the fall, to help pinpoint subsequent outbreaks.

The solutions it proposed weren’t rocket science—or even comparable to the dauntingly complex undertaking of developing a new vaccine. Any national plan to address testing deficits would likely be more on the level of “replicating UPS for an industry,” said Dr. Mike Pellini, the managing partner of Section 32, a technology and health care venture capital fund. “Imagine if UPS or FedEx didn’t have infrastructure to connect all the dots. It would be complete chaos.”

The plan crafted at the White House, then, set out to connect the dots. Some of those who worked on the plan were told that it would be presented to President Trump and likely announced in the Rose Garden in early April. “I was beyond optimistic,” said one participant. “My understanding was that the final document would make its way to the president over that weekend” and would result in a “significant announcement.”

But no nationally coordinated testing strategy was ever announced. The plan, according to the participant, “just went poof into thin air.”

In a statement, White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany said, “The premise of this article is completely false.”

This summer has illustrated in devastating detail the human and economic cost of not launching a system of national testing, which most every other industrialized nation has done. South Korea serves as the gold standard, with innovative “phone booth” and drive-through testing sites, results that get returned within 24 hours, and supportive isolation for those who test positive, including food drop-offs.

In the U.S., by contrast, cable news and front pages have been dominated by images of miles-long lines of cars in scorching Arizona and Texas heat, their drivers waiting hours for scarce diagnostic tests, and desperate Sunbelt mayors pleading in vain for federal help to expand testing capacity. In short, a “freaking debacle,” as one top public health expert put it.

We are just weeks away from dangerous and controversial school reopenings and the looming fall flu season, which the aborted plan had accounted for as a critical deadline for establishing a national system for quickly identifying new outbreaks and hot spots.

Without systematic testing, “We might as well put duct tape over our eyes, cotton in our ears, and hide under the bed,” said Dr. Margaret Bourdeaux, research director for the Harvard Medical School Program in Global Public Policy.

As it evolved, Kushner’s group called on the help of several top diagnostic-testing experts. Together, they worked around the clock, and through a forest of WhatsApp messages. The effort of the White House team was “apolitical,” said the participant, and undertaken “with the nation’s best interests in mind.”

Kushner’s team hammered out a detailed plan, which Vanity Fair obtained. It stated, “Current challenges that need to be resolved include uneven testing capacity and supplies throughout the US, both between and within regions, significant delays in reporting results (4-11 days), and national supply chain constraints, such as PPE, swabs, and certain testing reagents.”

The plan called for the federal government to coordinate distribution of test kits, so they could be surged to heavily affected areas, and oversee a national contact-tracing infrastructure. It also proposed lifting contract restrictions on where doctors and hospitals send tests, allowing any laboratory with capacity to test any sample. It proposed a massive scale-up of antibody testing to facilitate a return to work. It called for mandating that all COVID-19 test results from any kind of testing, taken anywhere, be reported to a national repository as well as to state and local health departments.

And it proposed establishing “a national Sentinel Surveillance System” with “real-time intelligence capabilities to understand leading indicators where hot spots are arising and where the risks are high vs. where people can get back to work.”

By early April, some who worked on the plan were given the strong impression that it would soon be shared with President Trump and announced by the White House. The plan, though imperfect, was a starting point. Simply working together as a nation on it “would have put us in a fundamentally different place,” said the participant.

But the effort ran headlong into shifting sentiment at the White House. Trusting his vaunted political instincts, President Trump had been downplaying concerns about the virus and spreading misinformation about it—efforts that were soon amplified by Republican elected officials and right-wing media figures. Worried about the stock market and his reelection prospects, Trump also feared that more testing would only lead to higher case counts and more bad publicity. Meanwhile, Dr. Deborah Birx, the White House’s coronavirus response coordinator, was reportedly sharing models with senior staff that optimistically—and erroneously, it would turn out—predicted the virus would soon fade away.

Against that background, the prospect of launching a large-scale national plan was losing favor, said one public health expert in frequent contact with the White House’s official coronavirus task force.

Most troubling of all, perhaps, was a sentiment the expert said a member of Kushner’s team expressed: that because the virus had hit blue states hardest, a national plan was unnecessary and would not make sense politically. “The political folks believed that because it was going to be relegated to Democratic states, that they could blame those governors, and that would be an effective political strategy,” said the expert.That logic may have swayed Kushner. “It was very clear that Jared was ultimately the decision maker as to what [plan] was going to come out,” the expert said.

Exclusive: CDC projects U.S. coronavirus death toll could top 180,000 by Aug. 22

As coronavirus cases have continued to rise in the U.S. throughout the summer, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is forecasting that the total American death toll from COVID-19 could hit 182,000 by the fourth week of August, according to an internal government document obtained by Yahoo News.

More than 150,000 Americans have died due to the coronavirus as of Thursday, according to the latest CDC numbers, which were included in a July 30 senior leadership brief.

Here’s the next level projections…

A new model from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) released Thursday increased the United States’ death projection to over 230,000 by early November.

A IHME forecast released July 22 projected 219,864 deaths in the United States, but the latest model estimates 230,822 deaths by Nov. 1, an increase of nearly 11,000 more deaths.

If individual states ease mask restrictions IHME projected 250,000 deaths due to COVID-19 in the United States.

With citizens universally wearing masks, IHME projected 198,000 COVID-19 deaths, a decrease of 32,000 deaths from the agency’s projected mark.

How Jared Kushner’s Secret Testing Plan “Went Poof Into Thin Air”

This spring, a team working under the president’s son-in-law produced a plan for an aggressive, coordinated national COVID-19 response that could have brought the pandemic under control. So why did the White House spike it in favor of a shambolic 50-state response?

On March 31, three weeks after the World Health Organization designated the coronavirus outbreak a global pandemic, a DHL truck rattled up to the gray stone embassy of the United Arab Emirates in Washington, D.C., delivering precious cargo: 1 million Chinese-made diagnostic tests for COVID-19, ordered at the behest of the Trump administration.

Normally, federal government purchases come with detailed contracts, replete with acronyms and identifying codes. They require sign-off from an authorized contract officer and are typically made public in a U.S. government procurement database, under a system intended as a hedge against waste, fraud, and abuse.

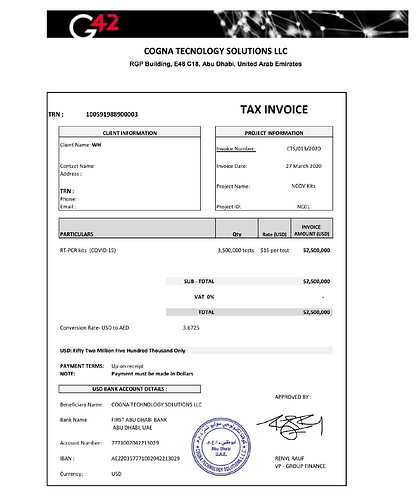

This purchase did not appear in any government database. Nor was there any contract officer involved. Instead, it was documented in an invoice obtained by Vanity Fair, from a company, Cogna Technology Solutions (its own name misspelled as “Tecnology” on the bill), which noted a total order of 3.5 million tests for an amount owed of $52 million. The “client name” simply noted “WH.”

Over the next three months, the tests’ mysterious provenance would spark confusion and finger-pointing. An Abu Dhabi–based artificial intelligence company, Group 42, with close ties to the UAE’s ruling family, identified itself as the seller of 3.5 million tests and demanded payment. Its requests were routed through various divisions within Health and Human Services, whose lawyers sought in vain for a bona fide contracting officer.

During that period, more than 2.4 million Americans contracted COVID-19 and 123,331 of them died of the illness. First in New York, and then in states around the country, governors, public health experts, and frightened citizens sounded the alarm that a critical shortage of tests, and the ballooning time to get results, were crippling the U.S. pandemic response.

But the million tests, some of which were distributed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency to several states, were of no help. According to documents obtained by Vanity Fair, they were examined in two separate government laboratories and found to be “contaminated and unusable.”

Group 42 representatives did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

The invoice for 3.5 million COVID-19 tests listed the client name as "WH."

TEAM JARED

The secret, and legally dubious, acquisition of those test kits was the work of a task force at the White House, where Jared Kushner, President Donald Trump ’s son-in-law and special adviser, has assumed a sprawling role in the pandemic response. That explains the “WH” on the invoice. While it’s unclear whether Kushner himself played a role in the acquisition, improper procurement of supplies “is a serious deal,” said a former White House staffer. “That is appropriations 101. That would be not good .”

Though Kushner’s outsized role has been widely reported, the procurement of Chinese-made test kits is being disclosed here for the first time. So is an even more extraordinary effort that Kushner oversaw: a secret project to devise a comprehensive plan that would have massively ramped up and coordinated testing for COVID-19 at the federal level.

Six months into the pandemic, the United States continues to suffer the worst outbreak of COVID-19 in the developed world. Considerable blame belongs to a federal response that offloaded responsibility for the crucial task of testing to the states. The irony is that, after assembling the team that came up with an aggressive and ambitious national testing plan, Kushner then appears to have decided, for reasons that remain murky, to scrap its proposal. Today, as governors and mayors scramble to stamp out epidemics plaguing their populations, philanthropists at the Rockefeller Foundation are working to fill the void and organize enough testing to bring the nationwide epidemic under control.

Inside the White House, over much of March and early April, Kushner’s handpicked group of young business associates, which included a former college roommate, teamed up with several top experts from the diagnostic-testing industry. Together, they hammered out the outline of a national testing strategy. The group—working night and day, using the encrypted platform WhatsApp—emerged with a detailed plan obtained by Vanity Fair.

Rather than have states fight each other for scarce diagnostic tests and limited lab capacity, the plan would have set up a system of national oversight and coordination to surge supplies, allocate test kits, lift regulatory and contractual roadblocks, and establish a widespread virus surveillance system by the fall, to help pinpoint subsequent outbreaks.

The solutions it proposed weren’t rocket science—or even comparable to the dauntingly complex undertaking of developing a new vaccine. Any national plan to address testing deficits would likely be more on the level of “replicating UPS for an industry,” said Dr. Mike Pellini, the managing partner of Section 32, a technology and health care venture capital fund. “Imagine if UPS or FedEx didn’t have infrastructure to connect all the dots. It would be complete chaos.”

The plan crafted at the White House, then, set out to connect the dots. Some of those who worked on the plan were told that it would be presented to President Trump and likely announced in the Rose Garden in early April. “I was beyond optimistic,” said one participant. “My understanding was that the final document would make its way to the president over that weekend” and would result in a “significant announcement.”

But no nationally coordinated testing strategy was ever announced. The plan, according to the participant, “just went poof into thin air.”

In a statement, White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany said, “The premise of this article is completely false.”

This summer has illustrated in devastating detail the human and economic cost of not launching a system of national testing, which most every other industrialized nation has done. South Korea serves as the gold standard, with innovative “phone booth” and drive-through testing sites, results that get returned within 24 hours, and supportive isolation for those who test positive, including food drop-offs.

In the U.S., by contrast, cable news and front pages have been dominated by images of miles-long lines of cars in scorching Arizona and Texas heat, their drivers waiting hours for scarce diagnostic tests, and desperate Sunbelt mayors pleading in vain for federal help to expand testing capacity. In short, a “freaking debacle,” as one top public health expert put it.

We are just weeks away from dangerous and controversial school reopenings and the looming fall flu season, which the aborted plan had accounted for as a critical deadline for establishing a national system for quickly identifying new outbreaks and hot spots.

Without systematic testing, “We might as well put duct tape over our eyes, cotton in our ears, and hide under the bed,” said Dr. Margaret Bourdeaux, research director for the Harvard Medical School Program in Global Public Policy.

Though President Trump likes to trumpet America’s sheer number of tests, that metric does not account for the speed of results or the response to them, said Dr. June-Ho Kim, a public health researcher at Ariadne Labs, a collaboration between Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who leads a team studying outlier countries with successful COVID-19 responses. “If you’re pedaling really hard and not going anywhere, it’s all for naught.”

With no bankable national plan, the effort to create one has fallen to a network of high-level civilians and nongovernmental organizations. The most visible effort is led by the Rockefeller Foundation and its soft-spoken president, Dr. Rajiv Shah. Focused and determinedly apolitical, Shah, 47, is now steering a widening and bipartisan coalition that includes three former FDA commissioners, a Nobel Prize–winning economist, a movie star, and 27 American cities, states, and tribal nations, all toward the far-reaching goal of getting to 30 million COVID-19 tests a week by autumn, up from the current rate of roughly 5.5 million a week.

“We know what has to be done: broad and ubiquitous testing tied to broad and effective contact tracing,” until a vaccine can be widely administered, Shah told Vanity Fair. “It takes about five minutes for anyone to understand that is the only path forward to reopening and recovering.” Without that, he said, “Our country is going to be stuck facing a series of rebound epidemics that are highly consequential in a really deleterious way.”

AN ABORTED PLAN

Countries that have successfully contained their outbreaks have empowered scientists to lead the response. But when Jared Kushner set out in March to solve the diagnostic-testing crisis, his efforts began not with public health experts but with bankers and billionaires. They saw themselves as the “A-team of people who get shit done,” as one participant proclaimed in a March Politico article.

Kushner’s brain trust included Adam Boehler, his summer college roommate who now serves as chief executive officer of the newly created U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, a government development bank that makes loans overseas. Other group members included Nat Turner, the cofounder and CEO of Flatiron Health, which works to improve cancer treatment and research.

A Morgan Stanley banker with no notable health care experience, Jason Yeung took a leave of absence to join the task force. Along the way, the group reached out for advice to billionaires, such as Silicon Valley investor Marc Andreessen.

The group’s collective lack of relevant experience was far from the only challenge it faced. The obstacles arrayed against any effective national testing effort included: limited laboratory capacity, supply shortages, huge discrepancies in employers’ abilities to cover testing costs for their employees, an enormous number of uninsured Americans, and a fragmented diagnostic-testing marketplace.

According to one participant, the group did not coordinate its work with a diagnostic-testing team at Health and Human Services, working under Admiral Brett Giroir, who was appointed as the nation’s “testing czar” on March 12. Kushner’s group was “in their own bubble,” said the participant. “Other agencies were in their own bubbles. The circles never overlapped.”

In the White House statement, McEnany responded, “Jared and his team worked hand-in-hand with Admiral Giroir. The public-private teams were embedded with Giroir and represented a single and united administration effort that succeeded in rapidly expanding our robust testing regime and making America number one in testing.”

As it evolved, Kushner’s group called on the help of several top diagnostic-testing experts. Together, they worked around the clock, and through a forest of WhatsApp messages. The effort of the White House team was “apolitical,” said the participant, and undertaken “with the nation’s best interests in mind.”

Kushner’s team hammered out a detailed plan, which Vanity Fair obtained. It stated, “Current challenges that need to be resolved include uneven testing capacity and supplies throughout the US, both between and within regions, significant delays in reporting results (4-11 days), and national supply chain constraints, such as PPE, swabs, and certain testing reagents.”

The plan called for the federal government to coordinate distribution of test kits, so they could be surged to heavily affected areas, and oversee a national contact-tracing infrastructure. It also proposed lifting contract restrictions on where doctors and hospitals send tests, allowing any laboratory with capacity to test any sample. It proposed a massive scale-up of antibody testing to facilitate a return to work. It called for mandating that all COVID-19 test results from any kind of testing, taken anywhere, be reported to a national repository as well as to state and local health departments.

And it proposed establishing “a national Sentinel Surveillance System” with “real-time intelligence capabilities to understand leading indicators where hot spots are arising and where the risks are high vs. where people can get back to work.”

By early April, some who worked on the plan were given the strong impression that it would soon be shared with President Trump and announced by the White House. The plan, though imperfect, was a starting point. Simply working together as a nation on it “would have put us in a fundamentally different place,” said the participant.

But the effort ran headlong into shifting sentiment at the White House. Trusting his vaunted political instincts, President Trump had been downplaying concerns about the virus and spreading misinformation about it—efforts that were soon amplified by Republican elected officials and right-wing media figures. Worried about the stock market and his reelection prospects, Trump also feared that more testing would only lead to higher case counts and more bad publicity. Meanwhile, Dr. Deborah Birx, the White House’s coronavirus response coordinator, was reportedly sharing models with senior staff that optimistically—and erroneously, it would turn out—predicted the virus would soon fade away.

Against that background, the prospect of launching a large-scale national plan was losing favor, said one public health expert in frequent contact with the White House’s official coronavirus task force.

Most troubling of all, perhaps, was a sentiment the expert said a member of Kushner’s team expressed: that because the virus had hit blue states hardest, a national plan was unnecessary and would not make sense politically. “The political folks believed that because it was going to be relegated to Democratic states, that they could blame those governors, and that would be an effective political strategy,” said the expert.

That logic may have swayed Kushner. “It was very clear that Jared was ultimately the decision maker as to what [plan] was going to come out,” the expert said.

In her statement, McEnany said, “The article is completely incorrect in its assertion that any plan was stopped for political or other reasons. Our testing strategy has one goal in mind—delivering for the American people—and is being executed and modified daily to incorporate new facts on the ground.”

On April 27, Trump stepped to a podium in the Rose Garden, flanked by members of his coronavirus task force and leaders of America’s big commercial testing laboratories, Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp, and finally announced a testing plan: It bore almost no resemblance to the one that had been forged in late March, and shifted the problem of diagnostic testing almost entirely to individual states.

Under the plan released that day, the federal government would act as a facilitator to help increase needed supplies and rapidly approve new versions of diagnostic-testing kits. But the bulk of the effort to operate testing sites and find available labs fell to the states.

“I had this naive optimism: This is too important to be caught in a partisan filter of how we view truth and the world,” said Rick Klausner, a Rockefeller Foundation adviser and former director of the National Cancer Institute. “But the federal government has decided to abrogate responsibility, and basically throw 50 states onto their own.”

THE SUMMER OF DISASTER

It soon became clear that ceding testing responsibility to the states was a recipe for disaster, not just in Democratic-governed areas but across the country.

In April, Phoenix, Arizona, was struggling just to provide tests to its health care workers and patients with severe symptoms of COVID-19. When Mayor Kate Gallego reached out to the federal government for help, she got an unmistakable message back: America’s fifth-largest city was on its own. “We didn’t have a sufficient number of cases to warrant” the help, Gallego told Vanity Fair.

Phoenix found itself in a catch-22, which the city’s government relations manager explained to lawyers in an April 21 email obtained by Vanity Fair through a public records request: “On a call with the county last week the Mayor was told that the region has [not] received FEMA funds related to testing because we don’t have bad numbers. The problem with that logic is that the Mayor believes we don’t have bad numbers because [of] a lack of testing.”

In June, Phoenix’s case counts began to rise dramatically. At a drive-through testing site near her house, Gallego saw miles-long lines of cars waiting in temperatures above 100 degrees. “We had people waiting 13 hours to get a test,” said Gallego. “These are people who are struggling to breathe, whose bodies ache, who have to sit in a car for hours. One man, his car had run out of gas and he had to refill while struggling to breathe.”

Gallego’s own staff members were waiting two weeks to get back test results, a period in which they could have been unwittingly transmitting the virus. “The turnaround times are way beyond what’s clinically relevant,” said Dr. James Lawler, executive director of international programs and innovation at the Global Center for Health Security at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

By July 5, Gallego was out of patience. She went on ABC News, wearing a neon-pink blouse, and politely blasted the federal response: “We’ve asked FEMA if they could come and do community-based testing here. We were told they’re moving away from that, which feels like they’re declaring victory while we’re still in crisis mode.”

Three days later, at a press conference, the White House’s testing czar, Admiral Giroir, blasted her back by name. Claiming that the federal government was already operating or contributing support for 41 Phoenix testing sites, he said: “Now, two days ago, I heard that Mayor Gallego was unhappy because there was no federal support…. It was clear to me that Phoenix was not in tune with all the things that the state were doing.”

Gallego recounted how her mother “just happened to catch this on CNN. She sent me a text message saying, ‘I don’t think they like you at the White House.’”

Despite Giroir’s defensiveness, however, Gallego ultimately prevailed in her public demand for help: Health and Human Services agreed to set up a surge testing site in Phoenix. “The effect was, we had to be in a massive crisis before they would help,” said Gallego.

And that is where the U.S. finds itself today—in a massive testing crisis. States have been forced to go their own way, amid rising case counts, skyrocketing demand for tests, and dwindling laboratory capacity. By mid-July, Quest Diagnostics announced that the average time to turn around test results was seven days.

It is obvious to experts that 50 individual states cannot effectively deploy testing resources amid vast regulatory, financial, and supply-chain obstacles. The diagnostic-testing industry is a “loosely constructed web,” said Dr. Pellini of Section 32, “and COVID-19 is a stage five hurricane.”

Dr. Lawler likened the nation’s balkanized testing infrastructure to the “early 20th century, when each city had its own electrical grid and they weren’t connected.” If one area lost power, “you couldn’t support it by diverting power from another grid.”

Experts are now warning that the U.S. testing system is on the brink of collapse. “We are at a very bad moment here,” said Margaret Bourdeaux. “We are about to lose visibility on this monster and it’s going to rampage through our whole country. This is a massive emergency.”

THE PLOT TO SAVE AMERICA

In late January, Rajiv Shah, president of the Rockefeller Foundation, went to Davos, Switzerland, and served on a panel at the World Economic Forum with climate activist Greta Thunberg. There, he had coffee with WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, whom he’d known from his years working in global public health, first at the Gates Foundation and then as director of USAID, an international development agency within the U.S. government.

Shah returned to New York, and to the Rockefeller Foundation headquarters, with a clear understanding: SARS-CoV-2 was going to be the big one.

The Rockefeller Foundation, which aims to address global inequality with a $4.4 billion endowment, helped create America’s modern public health system through the early work of the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission to eradicate hookworm disease. Shah immediately began to refocus the foundation on the coming pandemic, and hired a worldwide expert, Dr. Jonathan Quick, to guide its response.

Meanwhile, he kept watching and waiting for what he assumed would be a massive federal mobilization. “The normal [strong] federal emergency response, protocols, guidance, materials, organization, and leadership were not immediately taking form,” he said. “It was pretty obvious the right things weren’t happening.”

As director of USAID from 2009 to 2015, Shah led the U.S. response to both the Haiti earthquake and the West African Ebola outbreak, and knew that the “relentless” collection of real-time metrics in a disaster was essential.

During the Ebola outbreak, which he managed from West Africa, he brought in a world-famous European epidemiologist, Hans Rosling, and President Barack Obama ’s chief information officer to develop a detailed set of metrics, update them continuously in a spreadsheet, and send them daily to 25 top U.S. government officials. When it comes to outbreaks, said Shah, “If you don’t get this thing early, you’re chasing an exponentially steep curve.”

On April 21, the Rockefeller Foundation released a detailed plan for what it described as the “largest public health testing program in American history,” a massive scale-up from roughly 1 million tests a week at the time to 3 million a week by June and 30 million by the fall.

Estimating the cost at $100 billion, it proposed an all-hands-on-deck approach that would unite federal, state, and local governments; academic institutions; and the private and nonprofit sectors. Together, they would rapidly optimize laboratory capacity, create an emergency supply chain, build a 300,000-strong contact-tracing health corps, and create a real-time public data platform to guide the response and prevent reemergence.

The Rockefeller plan sought to do exactly what the federal government had chosen not to: create a national infrastructure in a record-short period of time. “Raj doesn’t do non-huge things,” said Andrew Sweet, the Rockefeller Foundation’s managing director for COVID-19 response and recovery. In a discussion with coalition members, Dr. Anthony Fauci called the Rockefeller plan “music to my ears.”

Reaching out to state and local governments, the foundation and its advisers soon became flooded with calls for help from school districts, hospital systems, and workplaces, all desperate for guidance. In regular video calls, a core advisory team that includes Shah, former FDA commissioner Mark McClellan, former National Cancer Institute director Rick Klausner, and Section 32’s Mike Pellini worked through how best to support members of its growing coalition.

Schools “keep hitting refresh on the CDC website and nothing’s changed in the last two months,” Shah told his colleagues in a video meeting in June. In the absence of trustworthy federal guidance, the Rockefeller team hashed out an array of issues: How should schools handle symptomatic and asymptomatic students? What about legal liability? What about public schools that were too poor to even afford a nurse?

(Last week, the CDC issued new guidelines that enthusiastically endorsed reopening schools and downplayed the risks, after coming under heavy pressure from President Trump to revise guidelines that he said were “very tough and expensive.”)

Through a testing-solutions group, the foundation is collaborating with city, state, and other testing programs, including those on Native American reservations, and helping to bolster them.

“They came on board and turbocharged us,” said Ann Lee, CEO of the humanitarian organization CORE (Community Organized Relief Effort), cofounded by Lee and the actor Sean Penn. CORE now operates 44 testing sites throughout the U.S., including Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles and mobile units within the Navajo Nation, which also offer food and essential supplies.

It may seem impossible for anyone but the federal government to scale up diagnostic testing one hundred-fold through a painstaking and piecemeal approach. But in private conversations, dispirited members of the White House task force urged members of the Rockefeller coalition to persist in their efforts. “Despite what we might be hearing, there is nothing being done in the administration on testing,” one of them was told on a phone call.

“It was a scary and telling moment,” the participant recounted.

A BAD GAMBLE

Despite the Rockefeller Foundation’s round-the-clock work to guide the U.S. to a nationwide testing system essential to reopening, the foundation has not yet been able to bend the most important curve of all: the Trump administration’s determined disinterest in big federal action.

On July 15, in a video call with journalists, Dr. Shah looked visibly frustrated. The next day, the Rockefeller Foundation would be releasing a follow-up report: It called on the federal government to commit $75 billion more to testing and contact tracing, work to break through the testing bottlenecks that had led to days-long delays in the delivery of test results, and vastly increase more rapid point-of-care tests.

Though speaking in a typically mild-mannered tone, Shah delivered a stark warning: “We fear the fall will be worse than the spring.” He added, putting it bluntly: “America is not near the top of countries who have handled COVID-19 effectively.”

Just three days later, news reports revealed that the Trump administration was trying to block any new funding for testing and contact tracing in the new coronavirus relief package being hammered out in Congress. As one member of the Rockefeller coalition said of the administration’s response, “We’re dealing with a schizophrenic organization. Who the hell knows what’s going on? It’s just insanity.”

On Friday, July 31, the U.S. House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus, which is investigating the federal response, will hold a hearing to examine the “urgent need” for a comprehensive national plan, at which Dr. Fauci, CDC director Robert Redfield, and Admiral Brett Giroir will testify. Among other things, the subcommittee is probing whether the Trump administration sought to suppress testing, in part due to Trump’s claim at his Tulsa, Oklahoma, rally in June that he ordered staff to “slow the testing down.”

The gamble that son-in-law real estate developers, or Morgan Stanley bankers liaising with billionaires, could effectively stand in for a well-coordinated federal response has proven to be dead wrong. Even the smallest of Jared Kushner’s solutions to the pandemic have entangled government agencies in confusion and raised concerns about illegality.

In the three months after the mysterious test kits arrived at the UAE embassy, diplomats there had been prodding the U.S. government to make good on the $52 million shipment. Finally, on June 26, lawyers for the Department of Health and Human Services sent a cable to the embassy, directed to the company which had misspelled its own name on the original invoice: Cogna Technology Solutions LLC.

The cable stated, “HHS is unable to remit payment for the test kits in question, as the Department has not identified any warranted United States contracting officer” or any contract documents involved in the procurement. The cable cited relevant federal contract laws that would make it “unlawful for the Government to pay for the test kits in question.”

But perhaps most relevant for Americans counting on the federal government to mount an effective response to the pandemic and safeguard their health, the test kits didn’t work. As the Health and Human Services cable to the UAE embassy noted: “When the kits were delivered they were tested in accordance with standard procedures and were found to be contaminated and unusable.”

An FDA spokesperson told Vanity Fair the tests may have been rendered ineffective because of how they were stored when they were shipped from the Middle East. “The reagents should be kept cold,” the spokesperson said.

Although officials with FEMA and Health and Human Services would not acknowledge that the tests even exist, stating only that there was no official government contract for them, the UAE’s records are clear enough. As a spokesperson for the UAE embassy confirmed, “the US Government made an urgent request for additional COVID-19 test kits from the UAE government. One million test kits were delivered to the US government by April 1. An additional 2.5 million test kits were delivered to the US government by April 20.”

The tests may not have worked, in other words, but Donald Trump would have been pleased at the sheer number of them.

Well shoot, so she did. I somehow missed that post.

You wonder what the end game in terms of T’s campaign is - given that he is losing so much support with his handling of the Coronavirus. These two articles suggest that engineering a vaccine to show up in October 2020 will be the best thing for T’s winning re-election.

The scientists wonder if it will be safe…

We are now learning, via an extraordinary new report in the New York Times, that many scientists fear that Trump will attempt the ultimate “October surprise.” These scientists — which include some inside the government — worry that Trump will thoroughly corrupt the process designed to ensure the safety and efficacy of any new vaccine against the coronavirus.

It is the perfect Trumpian paradox that his long record of just this sort of corruption underscores why this scenario should be entertained with deadly seriousness — but also why it will likely fail.

Article it links to - says that scientists fear of the safety of the virus, since it is geared to come out just before the election.

“DEADLINE: Enable broad access to the public by October 2020 , ” the first slide read, with the date in bold.

Given that it typically takes years to develop a vaccine, the timetable for the initiative, called Operation Warp Speed, was incredibly ambitious. With tens of thousands dying and tens of millions out of work, the crisis demanded an all-out public-private response, with the government supplying billions of dollars to pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, providing logistical support and cutting through red tape.

It escaped no one that the proposed deadline also intersected nicely with President Trump’s need to curb the virus before the election in November.

17-year-old boy loses both parents to COVID-19 within 4 days

Georgia Teen Loses Both Parents to Coronavirus 4 Days Apart: ‘They Were Loving Toward Everybody’

Justin Hunter said his parents, who were married for 35 years, both took proper precautions to prevent themselves from getting COVID-19

Covid-19 check list…graphic presentation

This is America, now buckling under the weight of an unpredictable virus for our own lack of leadership, foresight, and current adminstration which divided the country into multiple factions - at once yelling “Seek liberation” and then murmuring “wear a mask.”

Shameful…and sad.

Deep dive into how we got here…a long time to grapple with the holes in all of our assumptions as we endure this pandemic, which knows no bounds in a country ill prepared to fight and get it right.

Since the pandemic began, I have spoken with more than 100 experts in a variety of fields. I’ve learned that almost everything that went wrong with America’s response to the pandemic was predictable and preventable. A sluggish response by a government denuded of expertise allowed the coronavirus to gain a foothold. Chronic underfunding of public health neutered the nation’s ability to prevent the pathogen’s spread. A bloated, inefficient health-care system left hospitals ill-prepared for the ensuing wave of sickness. Racist policies that have endured since the days of colonization and slavery left Indigenous and Black Americans especially vulnerable to COVID‑19. The decades-long process of shredding the nation’s social safety net forced millions of essential workers in low-paying jobs to risk their life for their livelihood. The same social-media platforms that sowed partisanship and misinformation during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Africa and the 2016 U.S. election became vectors for conspiracy theories during the 2020 pandemic.

The U.S. has little excuse for its inattention. In recent decades, epidemics of SARS, MERS, Ebola, H1N1 flu, Zika, and monkeypox showed the havoc that new and reemergent pathogens could wreak. Health experts, business leaders, and even middle schoolers ran simulated exercises to game out the spread of new diseases. In 2018, I wrote an article for The Atlantic arguing that the U.S. was not ready for a pandemic, and sounded warnings about the fragility of the nation’s health-care system and the slow process of creating a vaccine. But the COVID‑19 debacle has also touched—and implicated—nearly every other facet of American society: its shortsighted leadership, its disregard for expertise, its racial inequities, its social-media culture, and its fealty to a dangerous strain of individualism.

SARS‑CoV‑2 is something of an anti-Goldilocks virus: just bad enough in every way. Its symptoms can be severe enough to kill millions but are often mild enough to allow infections to move undetected through a population. It spreads quickly enough to overload hospitals, but slowly enough that statistics don’t spike until too late. These traits made the virus harder to control, but they also softened the pandemic’s punch. SARS‑CoV‑2 is neither as lethal as some other coronaviruses, such as SARS and MERS, nor as contagious as measles. Deadlier pathogens almost certainly exist. Wild animals harbor an estimated 40,000 unknown viruses, a quarter of which could potentially jump into humans. How will the U.S. fare when “we can’t even deal with a starter pandemic?,” Zeynep Tufekci, a sociologist at the University of North Carolina and an Atlantic contributing writer, asked me.

Despite its epochal effects, COVID‑19 is merely a harbinger of worse plagues to come. The U.S. cannot prepare for these inevitable crises if it returns to normal, as many of its people ache to do. Normal led to this. Normal was a world ever more prone to a pandemic but ever less ready for one. To avert another catastrophe, the U.S. needs to grapple with all the ways normal failed us. It needs a full accounting of every recent misstep and foundational sin, every unattended weakness and unheeded warning, every festering wound and reopened scar.

…

The United States has correctly castigated China for its duplicity and the WHO for its laxity—but the U.S. has also failed the international community. Under President Donald Trump, the U.S. has withdrawn from several international partnerships and antagonized its allies. It has a seat on the WHO’s executive board, but left that position empty for more than two years, only filling it this May, when the pandemic was in full swing. Since 2017, Trump has pulled more than 30 staffers out of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s office in China, who could have warned about the spreading coronavirus. Last July, he defunded an American epidemiologist embedded within China’s CDC. America First was America oblivious.

Nothing like more shocking news affecting kids coming at us…

@Pet_Proletariat @MissJava - Would you move to Coronavirus please? THanks!

The U.S. Is Repeating Its Deadliest Pandemic Mistake

More than 40 percent of all coronavirus deaths in America have been in nursing homes. Here’s how it got so bad, and why there might still be more to come as cases surge in the Sun Belt.

In early April, Melvin Hector, a geriatrician in Tucson, Arizona, went into Sapphire of Tucson Nursing and Rehabilitation to check on one of his patients, who had been sent to the hospital the previous day. Hector found the woman in her room, wearing a surgical mask. She had been tested for COVID-19, but the results had not yet come back. When Hector asked for a mask for himself, he says a nurse responded, “We don’t have any.”

“I say to her, ‘You’re going into the room; the other staff are going in the room. She just went out to the hospital for a respiratory disease. And we don’t have any masks in the building?’” Hector recalled in a recent interview.

“They’re on order,” Hector remembered the nurse replying.

When Hector reported the situation to the Arizona Department of Health Services, he said Sapphire ended their working relationship. (In an email to me, Sapphire claimed that it had never suffered shortages of personal protective equipment, or PPE, and that the nurse said she didn’t know where to find more masks, not that there were none. In response to Sapphire’s statement, Hector said, “They lie.”)

To Hector, the episode was a microcosm of the myriad reasons why the United States has suffered so many COVID-19 deaths among nursing-home staff and residents. “Arizona is just one manifestation of a nationwide policy, an administrative policy to ignore this pandemic until it couldn’t be ignored,” Hector told me.

Few places represent the awful consequences of this neglect more than nursing homes. Of the country’s nearly 130,000 coronavirus deaths, more than 40 percent have been residents or employees of nursing homes and long-term-care facilities. One in five facilities has reported at least one death. In just one New Jersey nursing home, at least 53 residents died after the sick were housed with the healthy and staffers had little more than rudimentary face shields for protection.

Like so many other effects of the pandemic, the U.S.’s nursing-home COVID-19 crisis is hitting communities of color especially hard. According to research by Tamara Konetzka, a health economist at the University of Chicago, nursing homes with more residents of color were more likely to have a coronavirus case or death.

And yet, state and federal officials seem to be doing little to protect the elderly from further devastation. Coronavirus cases are now surging in Sun Belt states. In recent weeks, deaths in nursing homes have continued to climb in Florida, Georgia, Texas, South Carolina, and California, according to data from the COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic .

For now, overall deaths from COVID-19 are on a downward trajectory, potentially because COVID-19 patients are currently younger on average than those who fell ill in the Northeast this spring. However, experts say this doesn’t mean we won’t see more deaths in facilities like Sapphire of Tucson, where at least 58 residents and 36 staffers had tested positive for the coronavirus as of April, right at the time of Hector’s visit. (Arizona DHS has since inspected the facility.) Instead, the disease will likely spill from the young to the old, from bars into nursing homes.

Additional COVID-19 deaths in nursing homes are probable, and they will have been preventable. American nursing homes are chronically short-staffed and, even prior to the pandemic, were doing a poor job of controlling infections. Well into the crisis, authorities kept these facilities strapped for masks, tests, and other desperately needed equipment. And now, with the coronavirus raging across southern states, experts say the elderly will remain in danger in precisely the places so many of them typically go for a peaceful retirement. The tragedy of even more nursing-home deaths will be worsened by the fact that they could have been stopped.

Nursing homes’ COVID-19 deaths may seem inevitable, given that their elderly residents live cooped up together. But according to interviews with nearly a dozen nursing-home experts, it didn’t have to be this way. Worldwide, entire cities and individual nursing homes have remained coronavirus-free.

Take Hong Kong, population 7.5 million, which has reported no deaths from COVID-19 in its care homes. The city was scarred by the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, in 2003, during which it suffered nearly 300 deaths, or almost 40 percent of the global death toll. Nursing-home residents were more likely than the general public to get SARS, and 78 percent of residents who got the virus died from it, according to Terry Lum, the head of the department of social work and social administration at the University of Hong Kong. “We also had a few doctors and nurses get killed by SARS,” Lum told me. “Those are painful to watch. We didn’t want to see that ever again.”

Immediately after the 2003 outbreak, the Hong Kong government launched a revamped policy of infectious-disease control that required nursing homes to have a designated, government-trained infection-control officer, according to Lum. All nursing homes had to maintain at least a month’s supply of face masks and other PPE.

As soon as COVID-19 broke out in Hong Kong, in January of this year, its nursing homes halted nonurgent hospital trips among residents as well as family visitation, Lum said. Nursing-home staffers donned masks as they cared for the residents. Any nursing-home residents who caught COVID-19 were isolated in hospital coronavirus wards—not in nursing homes—until they had tested negative for the virus at least twice.

There was a human cost to the lack of family visits, Lum told me; patients who had dementia deteriorated more quickly without social interaction. But nursing-home administrators were certain that if even one COVID-19 case snuck into a nursing home, it would spark a conflagration with tragic results.

Some American nursing homes have likewise succeeded at keeping out the coronavirus. The Maryland Baptist Aged Home, a 30-resident, 100-year-old facility in Baltimore, avoided having any coronavirus cases. Its director, Derrick DeWitt, told me that in February, when the U.S. had just 15 known cases, he paused family visits and community meals, sent vendors and delivery drivers to a separate entrance, and brought in extra cleaning crews. The staff was trained on social distancing, screened regularly for their temperature and symptoms, and asked about their social activities. DeWitt, following the guidance of Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, said he ordered extra masks early, before they began to run out.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in the U.S., the virtual opposite played out. Nursing homes were ill-equipped, both literally and figuratively, to deal with the pandemic, and federal and state governments took a hands-off approach until it was too late. “I think we really dropped the ball here,” David C. Grabowski, a health-care-policy professor at Harvard Medical School, told me. “We have not done right by older adults who are living in nursing homes and those that care for them.”

Nursing homes were already struggling with infection control before the pandemic hit. A Government Accountability Office report published in May found that more than 80 percent of nursing homes were cited for infection-prevention deficiencies from 2013 to 2017. About half of those homes had “persistent problems and were cited across multiple years.” The report describes, among other incidents, a New York nursing home where a respiratory infection had sickened 38 residents. The home did not isolate or maintain a list of those who were sick, and continued to let residents eat meals together.

Lum said that, like many homes in the U.S., those in Hong Kong don’t tend to have a large number of staffers for each resident. Those staffers were just very, very careful about COVID-19. But in the U.S., some experts say that staffing shortages have made nursing homes unprepared to deal with a pandemic. One recent study that examined nursing-home data in Connecticut found that long-term-care facilities with lower nurse-staffing levels had higher rates of confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths.

Grabowski and other experts have also noted that nursing-home staffers tend to make little money, so many work multiple jobs. That creates an environment in which busy, undertrained personnel are shuffling quickly between patient rooms and nursing homes, taking the virus with them.

Experts generally agree that regular testing of staff and residents in nursing homes is key to halting outbreaks. “In order to keep the virus out of a nursing home, you need to be able to test staff regularly, every time they come in for a shift,” Katie Smith Sloan, the president of LeadingAge, an advocacy group for the elderly, told me. “And you need to get results within minutes, not days.”

But this spring, asymptomatic staffers brought the virus into homes, Konetzka and other experts believe, and these workers weren’t being tested. In Rhode Island—where more than three-quarters of COVID-19 deaths have taken place in nursing homes and assisted-living facilities, according to Kaiser Family Foundation data—one home did not begin testing residents and staff until after an employee had already died of COVID-19, as ProPublica reported. In June, a House subcommittee tasked with overseeing the country’s response to the coronavirus wrote a letter to the largest American nursing-home companies, and to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which regulates nursing homes; nationally, such facilities, the letter pointed out, still lack enough tests to meet the federal government’s recommendation that nursing homes test all residents and staff weekly. (In response to a request for comment, CMS said it was confident that all states had sufficient capacity for testing.)

And then there’s the issue of masks, which are considered another crucial element of stopping the spread of the coronavirus in nursing homes and elsewhere. Guidance on masks from CMS came much too late, Sloan said. According to a recent Reuters investigation, some nursing-home managers initially discouraged staff from wearing masks because they thought they wouldn’t help prevent infections.

Unlike those in Hong Kong, American nursing homes didn’t have months of masks stocked up. When the virus hit, they were tearing through their supplies at hundreds of times the rate they normally would. Hospitals, not nursing homes, were seen as the priority destination for the country’s precious reserves of masks. “We somehow expect individual nursing-home operators to compete against large hospitals and states in trying to get that equipment,” Konetzka said.

FEMA said it would ship supplies to nursing homes in May. But as Kaiser Health News reported, some homes received cloth masks instead of surgical ones or N95s, which are considered the gold standard for treating COVID-19 patients. (“FEMA did not ship N95 respirators or cotton masks as part of the nursing-home deliveries,” an agency spokesperson told me. “[The Health and Human Services Department] is providing cloth facial coverings as part of a separate, multipronged approach.”) Perhaps expectedly, months into the pandemic, many nursing homes ran out of masks and gowns. In early June, federal data showed that more than 250 nursing homes had no surgical masks and 800 more were a week away from running out.

To make matters worse, nursing homes across the U.S. took in COVID-19 patients from hospitals. In Minnesota, 77 percent of COVID-19 deaths have taken place in nursing homes, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Despite this, Minnesota hospitals discharged dozens of COVID-19 patients to nursing homes, the Minneapolis Star Tribune reported in May. “Hospitals were running out of space,” Sloan said. “And so they were transferring people to nursing homes. And our nursing homes were saying, ‘You can’t give us people who have COVID unless you give us PPE.’”