The World Health Organization said Monday the trajectory of the coronavirus pandemic is now “growing exponentially” at more than 4.4 million new Covid-19 cases a week over the last two months.

Maria Van Kerkhove, the agency’s technical lead for Covid-19, said “we’re in a critical point of the pandemic,” as some countries ease restrictions even as new cases per week are more than eight times higher than a year ago.

“This is not the situation we want to be in 16 months into a pandemic where we have proven control measures. It is the time right now where everyone has to take stock and have a reality check of what we need to be doing,” she said during a press briefing. “Vaccines and vaccinations are coming online, but they aren’t here yet in every part of the world.”

Covid-19 cases climbed by 9% across the globe last week — the seventh-consecutive weekly increase — and deaths jumped 5%, she said, asking governments to support their citizens in implementing pandemic safety measures.

Last month, WHO officials warned of a steady rise in Covid-19 cases and deaths in recent weeks, urging people to stick with mask mandates and social distancing rules as the world enters a critical phase of the pandemic.

The virus is “stronger, it’s faster” with the emergence of new variants that spread more easily and are more deadly than the original wild strain of the virus, Dr. Mike Ryan, the head of the WHO’s emergencies program, said March 31. “We’re all struggling” with and sick of restrictive lockdowns, he said.

This is a developing story. Please check back for updates

Not good.

Not sure if they will ever be viable…how much convincing could people believe that it is safe?

Dr. Kavita Patel told CNBC on Tuesday she believes the Food and Drug Administration’s recommendation that states pause the use of Johnson & Johnson’s single-shot Covid vaccine is likely to have lasting impacts on the nation’s efforts to combat the pandemic.

“This is a devastating blow to this J&J vaccine effort in the United States,” said Patel, a primary care physician in Washington who worked on health-care initiatives in the Obama administration while serving as director of policy for the Office of Intergovernmental Affairs and Public Engagement.

In an interview on “Squawk Box,” Patel said the supply of the two-shot vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna won’t be able to quickly make up the demand created by the J&J pause. This will delay U.S. vaccination efforts, she added.

The FDA’s recommendation, issued earlier Tuesday, came after six J&J vaccine recipients in the U.S. developed rare and severe blood-clotting issues.

Pt 2

NYTimes: How Safe Are You From Covid When You Fly?

How Safe Are You From Covid When You Fly?@matt Can u move to coronavirus spot plz. I maxxed my 10 inputs tthere. Thx.

Millions Are Skipping Their Second Doses of Covid-19 Vaccines - The New York Times

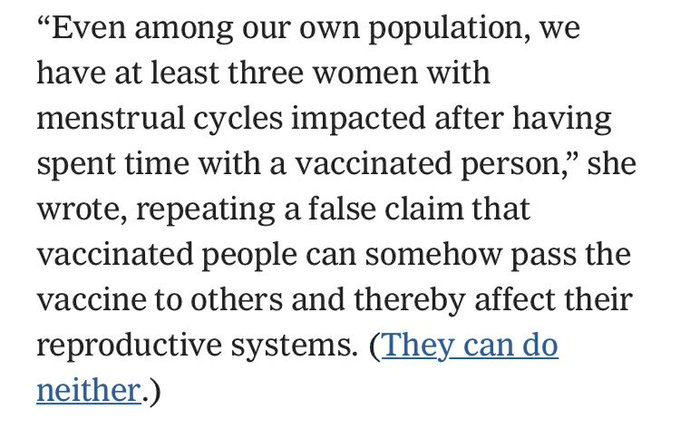

This might be the single stupidest thing since, well, we had “plant-based beer” just yesterday. But still.

The Centner Academy, a private school in Miami, citing false claims, has barred VACCINATED teachers from contact with students.

Damn it, Florida!

Perhaps the craziest part from the article above:

In the middle of a global pandemic killing tens of millions, Russia is using its vaccine, Sputnik V, to spread propaganda against the Pfizer vaccine.

One of the best lines from my college Stats teacher was “how to lie with statistics”. She was great.

This is an awful period in US history - targeting and mistreating black men to study syphilis.

Takes a lot of courage to move beyond this fear about what ‘science’ would bring to anyone black.

Eighty-four-year-old Florine Edwards was thrilled to receive her coronavirus vaccination in Memphis in March. “When I hear people say, ‘Well, I’m not sure,’ I say, ‘You be sure, because this is important,’ ” she explains. The same goes for Lillie Tyson Head, 76, who received her second dose in March as well, near Roanoke: “I had no doubts about whether I was going to get it.” And if someone asks Leo Ware, 82, who was vaccinated the same month near Orlando, whether to get a vaccine, he’d say: “Definitely. Without hesitation.”

What Edwards, Head and Ware share — besides their enthusiasm for getting vaccinated — is that they are descendants of Black men who were unwitting subjects of the notoriously unethical federal syphilis study in Tuskegee, Ala. Edwards’s father, Head’s father and both of Ware’s grandfathers were lured into the study without knowing they were being studied. Today, the deceit they suffered at the hands of public health officials is a common reason cited for vaccine hesitancy in communities of color. Yet, as I learned recently when I spoke with Tuskegee descendants, many are — in part because of their family histories — making a point of getting vaccinated and encouraging others to do the same.

The disgraced U.S. Public Health Service research project, formally titled the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male,” started in 1932 and lasted until 1972, when it was exposed by the Associated Press and quickly shut down. The study enrolled 623 Black men, about 400 of whom had the disease, with the rest serving as a control group. They were told they were being treated for “bad blood,” a term used at the time for a number of ailments. In the mid-1940s, when penicillin was discovered to be an effective treatment for syphilis, it was withheld from the men, as doctors continued to chart the course of the untreated disease.

Now more woke…thanks Joe for coming around.

Ex head of CDC…saying this today.

Scientists are worried about the Indian and Brazilian and British variants…WTFery.

The final legacy of the former guy: a never-ending cycle of vaccines and outbreaks because of his botched response and outright lies and selfishness.

Reaching ‘Herd Immunity’ Is Unlikely in the U.S., Experts Now Believe

Widely circulating coronavirus variants and persistent hesitancy about vaccines will keep the goal out of reach. The virus is here to stay, but vaccinating the most vulnerable may be enough to restore normalcy.

Early in the pandemic, when vaccines for the coronavirus were still just a glimmer on the horizon, the term “herd immunity” came to signify the endgame: the point when enough Americans would be protected from the virus so we could be rid of the pathogen and reclaim our lives.

Now, more than half of adults in the United States have been inoculated with at least one dose of a vaccine. But daily vaccination rates are slipping, and there is widespread consensus among scientists and public health experts that the herd immunity threshold is not attainable — at least not in the foreseeable future, and perhaps not ever.

Instead, they are coming to the conclusion that rather than making a long-promised exit, the virus will most likely become a manageable threat that will continue to circulate in the United States for years to come, still causing hospitalizations and deaths but in much smaller numbers.

How much smaller is uncertain and depends in part on how much of the nation, and the world, becomes vaccinated and how the coronavirus evolves. It is already clear, however, that the virus is changing too quickly, new variants are spreading too easily and vaccination is proceeding too slowly for herd immunity to be within reach anytime soon.

Continued immunizations, especially for people at highest risk because of age, exposure or health status, will be crucial to limiting the severity of outbreaks, if not their frequency, experts believe.

“The virus is unlikely to go away,” said Rustom Antia, an evolutionary biologist at Emory University in Atlanta. “But we want to do all we can to check that it’s likely to become a mild infection.”

The shift in outlook presents a new challenge for public health authorities. The drive for herd immunity — by the summer, some experts once thought possible — captured the imagination of large segments of the public. To say the goal will not be attained adds another “why bother” to the list of reasons that vaccine skeptics use to avoid being inoculated.

Yet vaccinations remain the key to transforming the virus into a controllable threat, experts said.

Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, the Biden administration’s top adviser on Covid-19, acknowledged the shift in experts’ thinking.

“People were getting confused and thinking you’re never going to get the infections down until you reach this mystical level of herd immunity, whatever that number is,” he said.

“That’s why we stopped using herd immunity in the classic sense,” he added. “I’m saying: Forget that for a second. You vaccinate enough people, the infections are going to go down.”

Why reaching the threshold is tough

Once the novel coronavirus began to spread across the globe in early 2020, it became increasingly clear that the only way out of the pandemic would be for so many people to gain immunity — whether through natural infection or vaccination — that the virus would run out of people to infect. The concept of reaching herd immunity became the implicit goal in many countries, including the United States.

Early on, the target herd immunity threshold was estimated to be about 60 to 70 percent of the population. Most experts, including Dr. Fauci, expected that the United States would be able to reach it once vaccines were available.

But as vaccines were developed and distribution ramped up through the winter and into the spring, estimates of the threshold began to rise. That is because the initial calculations were based on the contagiousness of the original version of the virus. The predominant variant now circulating in the United States, called B.1.1.7 and first identified in Britain, is about 60 percent more transmissible.

As a result, experts now calculate the herd immunity threshold to be at least 80 percent. If even more contagious variants develop, or if scientists find that immunized people can still transmit the virus, the calculation will have to be revised upward again.

Polls show that about 30 percent of the U.S. population is still reluctant to be vaccinated. That number is expected to improve but probably not enough. “It is theoretically possible that we could get to about 90 percent vaccination coverage, but not super likely, I would say,” said Marc Lipsitch, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Though resistance to the vaccines is a main reason the United States is unlikely to reach herd immunity, it is not the only one.

Herd immunity is often described as a national target. But that is a hazy concept in a country this large.

“Disease transmission is local,” Dr. Lipsitch noted.

“If the coverage is 95 percent in the United States as a whole, but 70 percent in some small town, the virus doesn’t care,” he explained. “It will make its way around the small town.”

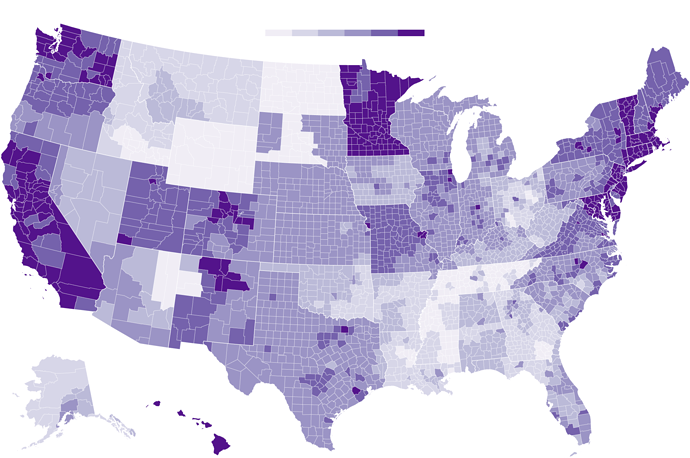

Uneven Willingness to Get Vaccinated Could Affect Herd Immunity

In some parts of the United States, inoculation rates may not reach the threshold needed to prevent the coronavirus from spreading easily.

How insulated a particular region is from the coronavirus depends on a dizzying array of factors.

Herd immunity can fluctuate with “population crowding, human behavior, sanitation and all sorts of other things,” said Dr. David M. Morens, a virologist and senior adviser to Dr. Fauci. “The herd immunity for a wealthy neighborhood might be X, then you go into a crowded neighborhood one block away and it’s 10X.”

Given the degree of movement among regions, a small virus wave in a region with a low vaccination level can easily spill over into an area where a majority of the population is protected.

At the same time, the connectivity between countries, particularly as travel restrictions ease, emphasizes the urgency of protecting not just Americans but everyone in the world, said Natalie E. Dean, a biostatistician at the University of Florida in Gainesville. Any variants that arise in the world will eventually reach the United States, she noted.

Many parts of the world lag far behind the United States on vaccinations. Less than 2 percent of the people in India have been fully vaccinated, for example, and less than 1 percent in South Africa, according to data compiled by The New York Times.

“We will not achieve herd immunity as a country or a state or even as a city until we have enough immunity in the population as a whole,” said Lauren Ancel Meyers, the director of the Covid-19 Modeling Consortium at the University of Texas at Austin.

What the future may hold

If the herd immunity threshold is not attainable, what matters most is the rate of hospitalizations and deaths after pandemic restrictions are relaxed, experts believe.

By focusing on vaccinating the most vulnerable, the United States has already brought those numbers down sharply. If the vaccination levels of that group continue to rise, the expectation is that over time the coronavirus may become seasonal, like the flu, and affect mostly the young and healthy.

“What we want to do at the very least is get to a point where we have just really sporadic little flare-ups,” said Carl Bergstrom, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Washington in Seattle. “That would be a very sensible target in this country where we have an excellent vaccine and the ability to deliver it.”

Over the long term — a generation or two — the goal is to transition the new coronavirus to become more like its cousins that cause common colds. That would mean the first infection is early in childhood, and subsequent infections are mild because of partial protection, even if immunity wanes.

Some unknown proportion of people with mild cases may go on to experience debilitating symptoms for weeks or months — a syndrome called “long Covid” — but they are unlikely to overwhelm the health care system.

“The vast majority of the mortality and of the stress on the health care system comes from people with a few particular conditions, and especially people who are over 60,” Dr. Lipsitch said. “If we can protect those people against severe illness and death, then we will have turned Covid from a society disrupter to a regular infectious disease.”

If communities maintain vigilant testing and tracking, it may be possible to bring the number of new cases so low that health officials can identify any new introduction of the virus and immediately stifle a potential outbreak, said Bary Pradelski, an economist at the National Center for Scientific Research in Grenoble, France. He and his colleagues described this strategy in a paper published on Thursday in the scientific journal The Lancet.

“Eradication is, I think, impossible at this stage,” Dr. Pradelski said. “But you want local elimination.”

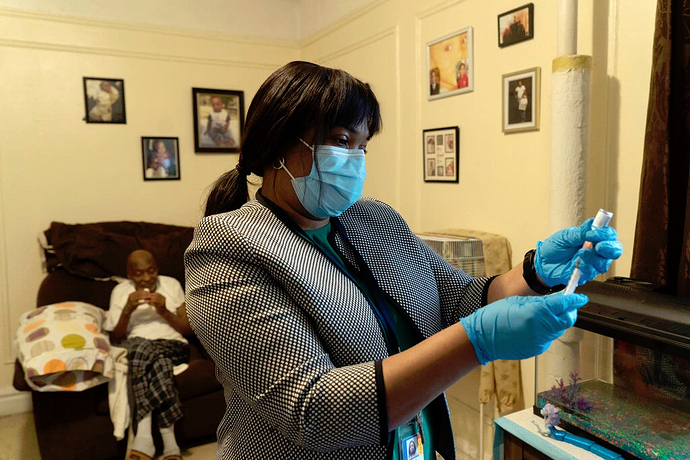

Darcia Bryden-Currie, a nurse, preparing a vaccine for Stephen Elliot at his home in the Bronx, part of an inoculation program for homebound people.

Vaccination is still the key

The endpoint has changed, but the most pressing challenge remains the same: persuading as many people as possible to get the shot.

Reaching a high level of immunity in the population “is not like winning a race,” Dr. Lipsitch said. “You have to then feed it. You have to keep vaccinating to stay above that threshold.”

Skepticism about the vaccines among many Americans and lack of access in some groups — homeless populations, migrant workers or some communities of color — make it a challenge to achieve that goal. Vaccine mandates would only make that stance worse, some experts believe.

A better approach would be for a trusted figure to address the root cause of the hesitancy — fear, mistrust, misconceptions, ease of access or a desire for more information, said Mary Politi, an expert in health decision making and health communication at Washington University in St. Louis.

People often need to see others in their social circle embracing something before they are willing to try it, Dr. Politi said. Emphasizing the benefits of vaccination to their lives, like seeing a family member or sending their children to school, might be more motivating than the nebulous idea of herd immunity.

“That would resonate with people more than this somewhat elusive concept that experts are still trying to figure out,” she added.

Though children spread the virus less efficiently than adults do, the experts all agreed that vaccinating children would also be important for keeping the number of Covid cases low. In the long term, the public health system will also need to account for babies, and for children and adults who age into a group with higher risk.

Unnerving scenarios remain on the path to this long-term vision.

Over time, if not enough people are protected, highly contagious variants may develop that can break through vaccine protection, land people in the hospital and put them at risk of death.

“That’s the nightmare scenario,” said Jeffrey Shaman, an epidemiologist at Columbia University.

How frequent and how severe those breakthrough infections are have the potential to determine whether the United States can keep hospitalizations and deaths low or if the country will find itself in a “mad scramble” every couple of years, he said.

“I think we’re going to be looking over our shoulders — or at least public health officials and infectious disease epidemiologists are going to be looking over their shoulders going: ‘All right, the variants out there — what are they doing? What are they capable of?” he said. “Maybe the general public can go back to not worrying about it so much, but we will have to.”

This.

Uneasy on those variant fronts…there will be no ‘normal’ for a long while.

Indeed. We had a solid chance to lead the world in shutting this down. America was perfectly positioned to do so, with our once-universally-trusted CDC and leadership. And he utterly destroyed all of that. This is 100% on him, at every level.

Yes.

Here’s another damning illustration of how off the course T forced it…with all the made-up nonsense that it is ‘going away.’

Much has been written about how the pandemic came to be, but not so well known are the details about how it was able to spread so quickly in the United States.

Author Michael Lewis has written a new book, The Premonition , that fills in those blanks. And it is a sweeping indictment of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Lewis, also author of Liar’s Poker, Moneyball, The Blind Side and The Big Short, says a public health doctor in California named Charity Dean is one of the people who saw the real danger of the virus before the rest of the country did.

“No one should have to be as brave as Charity Dean was as a local public health officer. To do her job, she had to be brave in a way that brought tears to my eyes,” Lewis tell NPR. “And when I first met her, I realized I had a character because all over her house were like these Post-it notes reminding her to be brave, like … ‘courage is a muscle memory’ or ‘the tallest oak in the forest was once just a little nut.’ She had all these kind of inspirational things. And when you get into the story of what Charity Dean … had to do on the ground, your hair stands up on the back of your neck.”

Lewis writes about how Dean tried and tried to get the state officials around her to look at the data and act to make sure the virus didn’t spread. She put it all on the line, her reputation, her job. And across the country, there was another group of doctors led by Carter Mescher trying to do the same thing at the federal level.

“It was incredible to me that there was this kind of secret group of seven doctors — they called themselves the Wolverines — who were positioned in interesting places in and around the federal government, who had been together for the better part of 15 years and who had come together whenever there was a threat of a disease outbreak to help organize the country’s response,” Lewis says.

But by 2020, the Trump administration had disbanded the pandemic response unit and these doctors were forced to go rogue. A mutual acquaintance put Charity Dean in touch with Carter Mescher.

“And Charity picked up all of Carter Mescher’s analysis. And she said it was like pouring water on a dying plant, that it was the first person she met who was thinking about this threat the way she was thinking about it,” Lewis says. “And so she’s very soon on the private calls. … Think of her as an actual battlefield commander. She’s in the war, in the trenches, as if she’s figured out in the course of her career in public health that there are no generals or the generals don’t understand how the, how the battle’s fought. And she’s going to have to kind of organize the strategy on the field.”

In January and February of 2020, hundreds of Americans in Wuhan, China, were flown back to the U.S. Considering how many people had died of COVID-19 in China at that point, it would have made sense to test those Americans who were coming back. But according to Lewis and his sources, then-CDC Director Robert Redfield refused to test them, saying it would amount to doing research on imprisoned persons.

“Redfield is a particularly egregious example, but he’s an expression of a much bigger problem. And if you just say, ‘oh, it’s the Trump administration’ or ‘oh, it’s Robert Redfield,’ you’re missing the bigger picture,” Lewis says. “And the bigger picture is we as a society have allowed institutions like the CDC to become very politicized. And this is a larger pattern in the U.S. government. More and more jobs being politicized, more and more people in these jobs being on shorter, tighter leashes. More the kind of person who ends up in the job being someone who is politically pleasing to whoever happens to be in the White House. And so … the conditions for Robert Redfield being in that job were created long ago.”

Lewis says he reached out to the CDC for comment, but the CDC wouldn’t speak to him.

“So what I did was guerilla journalism,” he says. “I interviewed individuals who were willing to talk to me either on background or off the record. And a couple people were on the record. But the CDC itself, I was told would not — didn’t want to talk to me.”

According to Lewis’ reporting, the CDC basically had two positions on the pandemic early on. Early on it was that there was nothing to see here — that this is not a big deal. It’s being overblown. And then there was this very quick pivot when it started spreading in the U.S. and the position became it’s too late and there’s nothing we can do.

“Charity Dean said the great shame of their behavior was they waited so long that we were never in a position to contain it,” Lewis says. “They pretended it wasn’t important until it was too late. That it could have been contained the way it was contained, say, by Australia. There were things we could do, many, many. And [if] they’d been more aggressive right up front. Many, many thousands of Americans would be alive today who are not.”

According to Lewis, the tragedy that became the American coronavirus pandemic was a perfect storm of the reaction of the president at the time, Donald Trump, the long history of politicization of the CDC and the lack of a public health care system all coming together.

“I think all my characters would say that because of the way we fail to govern ourselves, the way we fail to create a system, this would have been pretty bad under almost any administration and that it would have exposed the holes in the system and the weaknesses in the system, the absence of the system,” Lewis says.

Lewis followed these doctors inside and outside the federal government for many months as they tried to raise alarm bells and demand the kind of interventions that would have saved lives. But for him, Charity Dean stands apart for what she was willing to risk.

“You can’t believe what we are requiring of these people,” Lewis says. “And to me, there was something just unbelievably moving about this woman who had decided that even though she herself was full of fears for all kinds of good reasons, had willed herself to be brave for the sake of other people’s lives. And that had saved all these lives because she’d insisted on this trait in herself.”

It’s a trait that the system not only didn’t reward, it punished.

“In the pandemic, you saw this. Charity would tell you — and I think it’s true — that the pandemic has created a kind of selective pressure on our public health officers,” Lewis says. “And it’s removed the brave ones. The brave ones have all got their heads chopped off. So it’s sort of institutionalized a cowardice that we’re going to need to face up to so that this business of punishing people who are doing their damnedest to try to save us from ourselves has got to stop.”

New Study Estimates More Than 900,000 People Have Died Of COVID-19 In U.S.

A new study estimates that the number of people who have died of COVID-19 in the U.S. is more than 900,000, a number 57% higher than official figures.

Worldwide, the study’s authors say, the COVID-19 death count is nearing 7 million, more than double the reported number of 3.24 million.

The analysis comes from researchers at the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, who looked at excess mortality from March 2020 through May 3, 2021, compared it with what would be expected in a typical nonpandemic year, then adjusted those figures to account for a handful of other pandemic-related factors.

The final count only estimates deaths “caused directly by the SARS-CoV-2 virus,” according to the study’s authors. SARS-CoV-2 is the virus that causes COVID-19.

Researchers estimated dramatic undercounts in countries such as India, Mexico and Russia, where they said the official death counts are some 400,000 too low in each country. In some countries — including Japan, Egypt and several Central Asian nations — the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation’s death toll estimate is more than 10 times higher than reported totals.

“The analysis just shows how challenging it has been during the pandemic to accurately track the deaths — and actually, transmission — of COVID. And by focusing in on the total COVID death rate, I think we bring to light just how much greater the impact of COVID has been already and may be in the future,” said Dr. Christopher Murray, who heads the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

The group reached its estimates by calculating excess mortality based on a variety of sources, including official death statistics from various countries, as well as academic studies of other locations.

Then, it examined other mortality factors influenced by the pandemic. For example, some of the extra deaths were caused by increased opioid overdoses or deferred health care. On the other hand, the dramatic reduction in flu cases last winter and a modest drop in deaths caused by injury resulted in lower mortality in those categories than usual.

Researchers at UW ultimately concluded that the extra deaths not directly caused by COVID-19 were effectively offset by the other reductions in death rates, leaving them to attribute all of the net excess deaths to the coronavirus.

“When you put all that together, we conclude that the best way, the closest estimate, for the true COVID death is still excess mortality, because some of those things are on the positive side, other factors are on the negative side,” Murray said.

Experts are in agreement that official reports of COVID-19 deaths undercount the true death toll of the virus. Some countries only report deaths that take place in hospitals, or only when patients are confirmed to have been infected; others have poor health care access altogether.

“We see, for example, that when health systems get hit hard with individuals with COVID, understandably they devote their time to trying to take care of patients,” Murray said.

Because of that, many academics have sought to estimate a true COVID-19 death rate to understand better how the disease spreads.

The revised statistical model used by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation team produced numbers larger than many other analyses, raising some eyebrows in the scientific community.

“I think that the overall message of this (that deaths have been substantially undercounted and in some places more than others) is likely sound, but the absolute numbers are less so for a lot of reasons,” said William Hanage, an epidemiologist at Harvard University, in an email to NPR.

Last month, a group of researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University published a study in the medical journal JAMA that examined excess mortality rates in the U.S. through December.

While that team similarly found the number of excess deaths far exceeded the official COVID-19 death toll, it disagreed that the gap could be blamed entirely on COVID-19 and not other causes.

“Their estimate of excess deaths is enormous and inconsistent with our research and others,” said Dr. Steven Woolf, who led the Virginia Commonwealth team. “There are a lot of assumptions and educated guesses built into their model.”

Other researchers applauded the UW study, calling the researchers’ effort to produce a global model important, especially in identifying countries with small reported outbreaks but larger estimates of a true death toll, which could indicate the virus is spreading more widely than previously thought.

“We need to better understand the impact of COVID across the globe so that countries can understand the trajectory of the pandemic and figure out where to deploy additional resources, like testing supplies and vaccines to stop the spread,” said Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins.

Researchers at UW also released an updated forecast for the COVID-19 death count worldwide, estimating that roughly 2.5 million more people will die of COVID-19 between now and Sept. 1, driven in part by the dramatic surge of cases in India.

In the United States, researchers estimated roughly 44,000 more people will die of COVID-19 by September.

What we know for US so far…averted 4th wave.

Only problem, all those eager to get vaccinated, in the US, already have!

Now are left, the young, not very motivated, and people that might (or not) change their mind.

Am in Georgia.