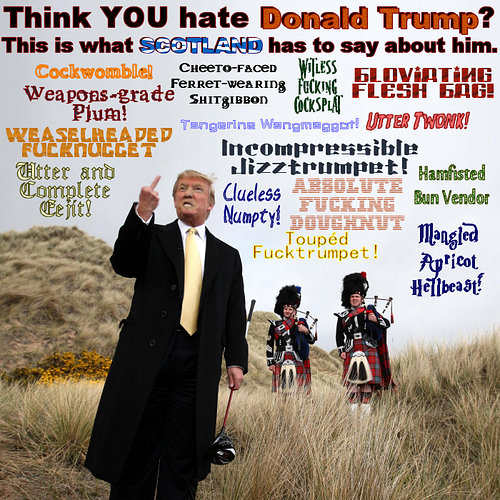

The Scottish have never tolerated Donnie well. I got all of this from 2016, before the election:

Been posted before I think - but still gold.

BTW my folks are from the Western Isles - as was Trump’s g’mother. Stornaway is one of my favourite places to be on earth.

and completely off-topic but one of my fav songs here is Peat and Diesel with their smash hit (at least in Scotland) Lovely Stornaway

That sounds terrifyingly right…

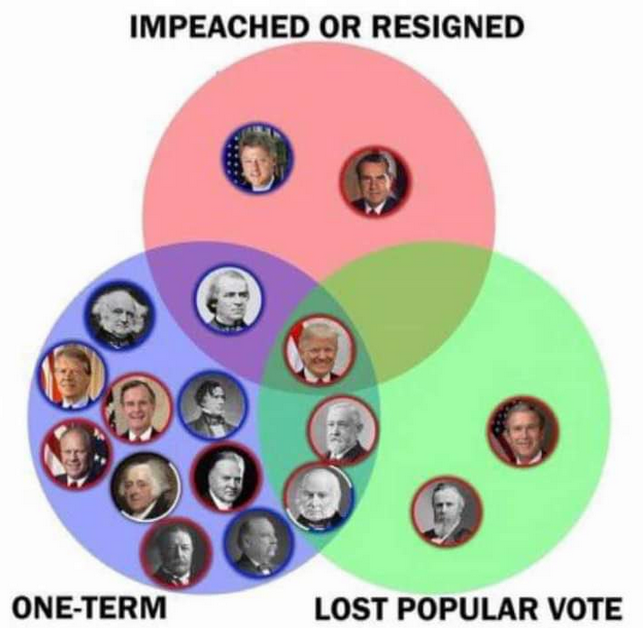

Yet this is reassuring.

I just went to lodge a complaint against the Trump campaign with the Federal Election Commission?

I can’t. Per their website, ALL complaints must be made in writing, & since June 18th the FEC is not able to receive complaints delivered by courier.

PS: I was lodging a complaint because when I tried to unsubscribe from the avalanche of Trump e-mails I keep getting begging for money after I filled out a single survey telling them how bad he is at everything, it instead sent me to another survey, then to WinRed, and did not unsubscribe.

Signs of a narcissist sociopath

Signs and symptoms of narcissistic personality disorder

- Grandiose sense of self-importance. …

- Lives in a fantasy world that supports their delusions of grandeur. …

- Needs constant praise and admiration. …

- Sense of entitlement. …

- Exploits others without guilt or shame. …

- Frequently demeans, intimidates, bullies, or belittles others.

And in other litigation events he is involved in a new up-date.

NYT Magazine section reviews where T is liable and what may happen to him post-Presidency. That NYC State has investigations ongoing right now, and they remain outside of what could be pardonable in advance of T’s leaving office, it remains to be seen what will stick and where these will go.

It would be wrong to think about Trump’s behavior as existing on the same spectrum as that of his post-Watergate predecessors. To see why, you have to first look back on the entire Trump presidency in a different way — one that sees his possibly criminal conduct not as a byproduct of the pursuit of a political agenda but as a central, self-perpetuating feature of his tenure. In this light, Trump’s potential criminality becomes a kind of throughline, the dots that connect his life as a businessman to his entry into politics and then onward across his four years as president. One potentially illegal act led Trump to the next: from his law-bending moves as a businessman, to his questionable campaign-finance practices, to his willingness to interfere with investigations into his conduct, to his acts of public corruption and, finally, to the seemingly illegal abuse of the powers of his office in order to remain in office.

The stakes of prosecuting Donald Trump may be high; but so are the costs of not prosecuting him, which would send a dangerous message, one that transcends even the presidency, about the country’s commitment to the rule of law. Trump has presented Biden — and America, really — with a very difficult dilemma. “This whole presidency has been about someone who thought he was above the law,” Anne Milgram, the former attorney general of New Jersey, told me. “If he isn’t held accountable for possible crimes, then he literally was above the law.”

Financial Crimes

Donald Trump’s singular relationship with the law, which long predated his presidency, was perhaps an inevitable consequence of his relationship with Roy Cohn during his formative years in business. It was Cohn who taught Trump that the law was not a set of inviolable rules but a system to beat and even work to your advantage, the most powerful tool in a businessman’s toolbox. “I decided long ago to make my own rules,” Cohn told Penthouse magazine in 1981. (Trump later passed along one of those rules to his first White House counsel, Donald McGahn, when he told him, “Lawyers don’t take notes.”)

As a businessman with an inherited and growing fortune, Trump engaged in a great deal of litigation — “I’m like a Ph.D. in litigation,” he joked at one campaign rally in 2016 — answering suits with countersuits; wearing down his adversaries with endless rounds of delays, motions and appeals; compelling his employees to sign sweeping nondisclosure agreements. At risk of defaulting on a $640 million loan from Deutsche Bank in 2008, Trump sued the institution for $3 billion, blaming it for helping cause the global financial meltdown that had made him temporarily insolvent. Unhappy with the $15 million property-tax valuation placed on a golf course that he had paid $47.5 million to buy and renovate, Trump sued the town of Ossining, N.Y., claiming that the property was worth only $1.4 million.

Trump had figured out something about the American system: You could solve a lot of problems with money, lawyers and a willingness to double down. This attitude led him, inexorably, toward business practices that tested the line of legality. After Trump’s financial struggles in the early 2000s made it more difficult for him to borrow money from established financial institutions, he sought partnerships with private individuals like the Russian oligarch Aras Agalarov, whom Senate investigators have linked to organized crime. (A spokesman for the Trump Organization challenged the notion that the company was struggling at the time and said that it in fact “enjoyed great success in the 2000s.”) Trump’s real estate training program, Trump University, was essentially a pyramid scheme, encouraging consumers, in particular the elderly, to purchase high-priced seminars for supposedly proprietary investment advice that in fact came from third-party marketing companies. Trump used money raised by his nonprofit foundation to settle lawsuits against his for-profit businesses (as well as to buy a gigantic painting of himself, which he had hung at one of his golf clubs). According to the congressional testimony of Trump’s longtime personal lawyer, Michael Cohen, Trump deliberately inflated the value of his assets by hundreds of millions of dollars in order to secure bank loans and cheaper insurance rates, and deflated their value to lower his tax burden. (A spokesman for the Trump Organization said Cohen’s claims were “completely untrue.”)

Trump’s tax strategy, enabled by a large team of accountants and lawyers, stretched the limits of tax avoidance and may well have crossed the line into tax fraud. Trump has steadfastly refused to disclose his tax returns, but a team of investigative reporters at The Times obtained reams of his tax data; what they revealed was startling. In 2010, Trump took a $72.9 million tax refund for an abandoned Atlantic City casino venture, which would require him to have received absolutely nothing in return for his investment, and he appears to have grossly overstated the value of several properties in order to claim larger deductions known as conservation easements. During Trump’s years on “The Apprentice,” he wrote off $70,000 in haircuts as a business expense. He also wrote off the expenses associated with a family compound in Westchester County by classifying it as an investment property, and he paid his daughter Ivanka more than $740,000 in consulting fees when she was an employee of the Trump Organization.

Most major financial crimes carry a five-year statute of limitations, so any illegal acts committed since 2015 would be chargeable. Both the New York attorney general, Letitia James — who entered office in 2019 vowing to use “every area of the law” to investigate President Trump — and the Manhattan district attorney, Cyrus R. Vance Jr., operate independently of the federal government, and even if Trump were to successfully engineer a pardon for himself, he would not be immune from state charges.

Vance’s inquiry appears to cover a range of possible white-collar crimes; one of his office’s filings made reference to “potentially widespread and protracted criminal conduct” at the Trump Organization. Tax fraud and insurance fraud have been mentioned explicitly in court documents, but some of the prosecutors and white-collar defense lawyers I spoke with suggested other possibilities, too. Given Trump’s history of doing business with foreign actors with a demonstrated need to conceal the sources of their income, another one might be money laundering. If investigators are able to establish that Trump engaged in a pattern of illegal activity, he could also be indicted under New York’s racketeering statute.

But prosecuting Trump under state law poses challenges of its own. New York’s state courts afford defendants far more protections than the federal courts. There are stricter rules governing evidence that can be presented to a grand jury, and even minor procedural errors can result in indictments being thrown out. “If you’re a white-collar defendant, you’d rather be in New York State court than in federal court any day of the week,” Daniel R. Alonso, who served as Vance’s top deputy from 2010 to 2014 and is now in private practice, told me.

You will find no argument here…

Points

President Donald Trump is worried his campaign’s legal team, led by his personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani, is composed of “fools that are making him look bad,” NBC News reported.

Giuliani and other campaign lawyers have so far failed to invalidate votes and reverse an apparent victory for President-elect Joe Biden.

Former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie on Sunday called Trump’s legal team a “national embarrassment.”

President Donald Trump is sweating over his campaign lawyers’ dismal and often outlandish efforts to reverse President-elect Joe Biden’s projected electoral victory.

Trump is worried that his campaign’s legal team, which is being led by his personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani, is composed of “fools that are making him look bad,” NBC News reported Monday.

That group, which has unironically called itself an “elite strike force team,” to date has failed to win any legal victories that would invalidate votes for Biden, the former Democratic vice president, even as they tout wildly broad claims of fraud for which they have offered no convincing evidence.

On Sunday, one of the team’s members, conspiracy theorist Sidney Powell, was effectively fired after suggesting — again without any proof — that the Republican governor and secretary of state of Georgia were part of a plot to rig the election for Biden.

Powell’s ouster came days after she made similarly over-the-top claims at a press conference at the Republican National Committee headquarters in Washington.

Trump has complained to White House aides and outside allies about how Giuliani and Powell conducted themselves at that event, NBC reported.

On Sunday before Powell got the axe, former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, a close Trump ally and former top federal prosecutor, called the president’s legal team a “national embarrassment.”

But when asked why Trump doesn’t fire Giuliani and other attorneys who remain on the team, a person familiar with the president’s thinking gave a profane shoulder shrug of an answer.

“Who the f— knows?” that person said to NBC News.

For now, Giuliani has kept his job as the president’s point man on the election challenge, even after a week in which he gave a widely derided argument in Pennsylvania federal court, only to see a judge on Saturday issue a scathing dismissal of the campaign’s vote challenge lawsuit.

Giuliani, who was once a top federal prosecutor in Manhattan, also presided over the press conference at RNC headquarters, where he stood and watched Powell promote the campaign’s most far-fetched vote fraud allegations to date.

At that event, Giuliani perspired so heavily that sweat apparently blackened from hair dye conspicuously ran down his cheeks as he made baseless allegations of electoral skullduggery.

Trump, who is obsessed with television and the personal appearances of people on it, was not happy with Giuliani’s look at the press conference, a person familiar with the president’s reaction told NBC News.

Also still on the Trump campaign team is senior legal advisor Jenna Ellis.

Within hours of the Trump campaign suffering its major defeat in the Pennsylvania election case Saturday night, Ellis tweeted that respected Republican pollster Frank Luntz had “MicroPenis Syndrome.”

Luntz’s sin was linking to a tweet from Ellis last week that suggested Giuliani, a former New York City mayor, was getting on swimmingly with the judge in the case.

“Best parody account on Twitter,” Luntz had japed.

“You media morons are all laughing at @RudyGiuliani, but he appears to have already established a great rapport with the judge, who is currently offering recommendations on martini bars for Team Trump in open court,” Ellis had written.

A spokesman for Trump’s campaign had no immediate comment on NBC News’ reporting.

Trump’s coup failed – but US democracy has been given a scare

The president pulled every lever to stay in power. It didn’t work, but how would the US handle a closer election?

In the end, the coup did not take place. In the most grudging manner possible, Donald Trump signalled on Monday night that the transition of power could begin.

That, a White House official told reporters, was as close as Trump will probably ever come to concession, but the machinery of transition has gathered momentum. Joe Biden’s incoming administration now has a government internet domain, is being briefed by government agencies and is due to receive federal funding.

The Pentagon quickly announced it would be providing support for the transfer of power. And one by one, senior Republicans – an especially timid category – are recognising the election result.

But there is no doubt US democracy has been given a scare. As the sense of imminent threat begins to fade, the convoluted inner workings of the electoral system are coming under scrutiny to determine whether it was as robust as its advocates had hoped – or whether the nation simply got lucky this time.

“I had long been in the camp of people who believed that the guardrails of democracy were working,” Katrina Mulligan, a former senior official in the justice department’s national security division. “But my view has actually shifted in the last few weeks as I watched some of this stuff play out. Now I actually think that we are depending far too much on fragile parts of our democracy, and expecting individuals, rather than institutions, to do the work the institution should be doing.”

Trump made no secret of his gameplan even before the election, and it has come into sharper focus with every madcap day since: cast doubt on the reliability of postal ballots, claim victory on election night before most of them were counted, and then sow enough confusion with allegations, justice department investigations and street mayhem with far-right militias to delay certification of the results.

Such a delay would create an opportunity for Republican-run state legislatures to step in and select their own electors to send to the electoral college, which formally decides who becomes president. That would produce a constitutional crisis that would ultimately be settled by the supreme court, which has a 6-3 Republican majority and has become increasingly politicised.For the plan to work it required political fealty to trump actual votes but, at several crucial decision points, that did not happen.

The key ingredient for a classic coup – a politically motivated military – was absent from the start, though not for want of Trump’s efforts. He tried to bring active duty troops on to the streets to quell the Black Lives Matter protests in the summer, but the defence secretary, Mark Esper, refused to cooperate.

After Esper was fired in the wake of the election, and Trump loyalists were installed in senior decision-making positions, the chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, General Mark Milley, used a planned public appearance at the dedication of an army museum to send a pointed message.

“We take an oath to the constitution,” Milley said. “We do not take an oath to a king or a queen, a tyrant or a dictator.”

The statement was greeted with some relief – but what was most striking was that it needed to be said at all.

The next lever of power that Trump tried to yank was the justice department and the FBI. The attorney general, William Barr, authorised US attorneys to conduct investigations into alleged voter fraud if there are “clear and apparently-credible allegations of irregularities”.

Can American democracy survive Donald Trump?

The opening of such investigations would have supercharged conspiracy theories and given more cover for state-level Republicans to delay certification of the votes. But justice department prosecutors rebelled. The official in charge of investigating electoral crimes, Richard Pilger, resigned and others made their objections public.

“The justice department, more than most institutions, is staffed by people who have a real healthy understanding of what democracy is and why it’s worth saving,” Mulligan, now national director for national security at the Center for American Progress, said. She added that the clarity of Biden’s win made it even less likely justice department officials would go along with such a dubious enterprise.

The next line of defence was state-level Republican officials involved in the machinery of certifying results. They came under intense pressure, including in a couple of cases a direct call from the president. In some cases, notably in Michigan, they buckled, but in most states they held firm, as in the case of the Georgia secretary of state, Brad Raffensperger, who confirmed Biden’s slim majority of victory and consequently became a pariah in his own party.

“Some folks here deserve medals and some simply met an extremely low bar,” said Rebecca Ingber, a former state department legal counsel, now professor at Cardozo law school. “This is a story about guardrails working, but it’s also a reminder about the fragility of those guardrails. At the end of the day, we are talking about humans, not robots.”

Similarly, even the most conservative judges turned away the fanciful claims of election fraud pursued by the Trump legal team, whose current score in the courts is one win and 35 losses.

It is possible more competent plotters could have done more damage. Trump appears to have left it until after the election to assemble a legal team, and ultimately handed control to his fiercely loyal, but erratic and hapless personal lawyer, Rudy Giuliani.

Ultimately Biden’s margin of victory (over 6 million nationwide and tens of thousands in most of the battlegrounds) was so clear, and evidence of fraud so slight, that even with better lawyers, the legal channel would have been near impossible.

But the 2020 experience has raised concerns about how US democracy would weather a closer election, and a more disciplined group determined to wield the power of the state to steal it. The militias, who were not coordinated enough to emerge as the intimidatory force Trump hoped for, could be stronger on the next occasion.

“President Trump’s rhetoric appealing to these groups has been dangerous from day one of his campaign, giving these groups tacit support for their illegal activities. And the lacklustre law enforcement response to public violence committed by these groups has exacerbated that problem,” said Michael German, a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice and who as an FBI special agent was tasked with infiltrating extremist groups. “Their ability to organise and recruit and test tactics and networks has been strengthened. So once there is an effort to police them, they will be much more difficult a problem.”

The 2020 election has also exposed a rapidly spreading rot in the foundation of the system – public confidence that it is fair. Some 70% of Republicans, despite the clear certified results, believe the vote was rigged.

“I do think we got lucky,” said Susan Hennessey, a former lawyer at the National Security Agency and executive editor of the Lawfare blog. “The dog didn’t bark but this was not for lack of trying and had circumstances been a little bit different, and had the margin been a little bit closer, I think we have a really clear demonstration that normative constraints are not going to prevent people from taking profoundly undemocratic measures.”

Trump’s meltdown over #DiaperDon really gets the Twitterverse going.

For a US president obsessed by size – his hands, his wealth, his crowds – Donald Trump made something of a bold U-turn on Thursday night by addressing the country from a desk seemingly designed for a leprechaun.

Trump said on Thursday he would leave the White House if the electoral college votes for the Democratic president-elect, Joe Biden – the closest he has come to admitting defeat – but his furniture stole the limelight.

While he harangued reporters and repeated unfounded allegations of electoral fraud, the internet zeroed in on his unusually small desk. Some called it symbolic of Trump’s diminished stature, some wondered if it was photoshopped (it wasn’t), most just laughed.

The actor Mark Hamill tweeted: “Maybe if you behave yourself, stop lying to undermine a fair election & start thinking of what’s good for the country instead of whining about how unfairly you are treated, you’ll be invited to sit at the big boy’s table.”

The hashtag #DiaperDon swiftly trended on Twitter, with people mocking the president as an infant banished to the children’s table for Thanksgiving.

Parker Molloy (@ParkerMolloy)May this be how we remember the Trump presidency: a baby at his tiny little desk throwing a tantrum pic.twitter.com/T26DjF1fL4

“Thought this pic was photoshopped, but nope, just hilariously symbolic! Mini desk. Tiny hands. Infinitesimally small soul,” tweeted Adam Lasnik.

Noah Maher (@noahsparc)

I still can’t quite believe this happened today.

Whoever suggested that desk … thank you.#tinydesk #TinyDeskDonald https://twitter.com/parkermolloy/status/1332126446886809602 pic.twitter.com/xKuU0DVjUD

Trump later sent a blizzard of tweets accusing the media of misreporting his comments and Twitter of making up “negative stuff” for its trending section.

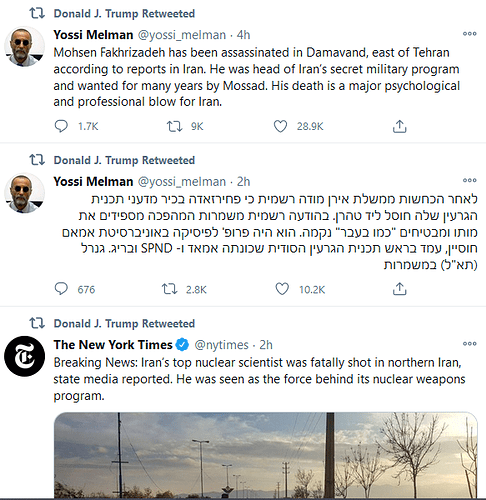

Trump is taking credit for the assassination of a top Iranian nuclear scientist. He has a thing for combining holidays with illegal assassinations.

The whole scheme of how Trump expected to win, steal, set up conspiracies to get the election clearly called for Biden, to go in Trump’s direction. What a farce and the lengths that he went to get his way…

The facts were indisputable: President Trump had lost.

But Trump refused to see it that way. Sequestered in the White House and brooding out of public view after his election defeat, rageful and at times delirious in a torrent of private conversations, Trump was, in the telling of one close adviser, like “Mad King George, muttering, ‘I won. I won. I won.’ ”

However cleareyed Trump’s aides may have been about his loss to President-elect Joe Biden, many of them nonetheless indulged their boss and encouraged him to keep fighting with legal appeals. They were “happy to scratch his itch,” this adviser said. “If he thinks he won, it’s like, ‘Shh . . . we won’t tell him.’ ”

Trump campaign pollster John McLaughlin, for instance, discussed with Trump a poll he had conducted after the election that showed Trump with a positive approval rating, a plurality of the country who thought the media had been “unfair and biased against him” and a majority of voters who believed their lives were better than four years earlier, according to two people familiar with the conversation, who spoke on t

The result was an election aftermath without precedent in U.S. history. With his denial of the outcome, despite a string of courtroom defeats, Trump endangered America’s democracy, threatened to undermine national security and public health, and duped millions of his supporters into believing, perhaps permanently, that Biden was elected illegitimately.he condition of anonymity to discuss private conversations. As expected, Trump lapped it up.

Trump’s allegations and the hostility of his rhetoric — and his singular power to persuade and galvanize his followers — generated extraordinary pressure on state and local election officials to embrace his fraud allegations and take steps to block certification of the results. When some of them refused, they accepted security details for protection from the threats they were receiving.

“It was like a rumor Whac-A-Mole,” said Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger. Despite being a Republican who voted for Trump, Raffensperger said he refused repeated attempts by Trump allies to get him to cross ethical lines. “I don’t think I had a choice. My job is to follow the law. We’re not going to get pushed off the needle on doing that. Integrity still matters.”

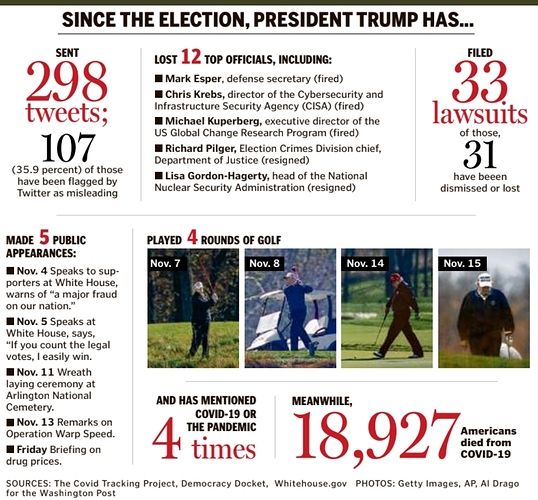

All the while, Trump largely abdicated the responsibilities of the job he was fighting so hard to keep, chief among them managing the coronavirus pandemic as the numbers of infections and deaths soared across the country. In an ironic twist, the Trump adviser tapped to coordinate the post-election legal and communications campaign, David Bossie, tested positive for the virus a few days into his assignment and was sidelined.

Only on Nov. 23 did Trump reluctantly agree to initiate a peaceful transfer of power by permitting the federal government to officially begin Biden’s transition — yet still he protested that he was the true victor.

The 20 days between the election on Nov. 3 and the greenlighting of Biden’s transition exemplified some of the hallmarks of life in Trump’s White House: a government paralyzed by the president’s fragile emotional state; advisers nourishing his fables; expletive-laden feuds between factions of aides and advisers; and a pernicious blurring of truth and fantasy.

Though Trump ultimately failed in his quest to steal the election, his weeks-long jeremiad succeeded in undermining faith in elections and the legitimacy of Biden’s victory.

This account of one of the final chapters in Trump’s presidency is based on interviews with 32 senior administration officials, campaign aides and other advisers to the president, as well as other key figures in his legal fight, many of whom spoke on the condition of anonymity to share details about private discussions and to candidly assess the situation.

In the days after the election, as Trump scrambled for an escape hatch from reality, the president largely ignored his campaign staff and the professional lawyers who had guided him through the Russia investigation and the impeachment trial, as well as the army of attorneys who stood ready to file legitimate court challenges.

Instead, Trump empowered loyalists who were willing to tell him what he wanted to hear — that he would have won in a landslide had the election not been rigged and stolen — and then to sacrifice their reputations by waging a campaign in courtrooms and in the media to convince the public of that delusion.

The effort culminated Nov. 19, when lawyers Rudolph W. Giuliani, Jenna Ellis and Sidney Powell spoke on the president’s behalf at the headquarters of the Republican National Committee to allege a far-reaching and coordinated plot to steal the election for Biden. They argued that Democratic leaders rigged the vote in a number of majority-Black cities, and that voting machines were tampered with by communist forces in Venezuela at the direction of Hugo Chávez, the Venezuelan leader who died seven years ago.

There was no evidence to support any of these claims.

The Venezuelan tale was too fantastical even for Trump, a man predisposed to conspiracy theories who for years has feverishly spread fiction. Advisers described the president as unsure about the latest gambit — made worse by the fact that what looked like black hair dye mixed with sweat had formed a trail dripping down both sides of Giuliani’s face during the news conference. Trump thought the presentation made him “look like a joke,” according to one campaign official who discussed it with him.

“I, like everyone else, have yet to see any evidence of it, but it’s a thriller — you’ve got Chávez, seven years after his death, orchestrating this international conspiracy that politicians in both parties are funding,” a Republican official said facetiously. “It’s an insane story.”

Aides said the president was especially disappointed in Powell when Tucker Carlson, host of Fox News’s most-watched program, assailed her credibility on the air after she declined to provide any evidence to support her fraud claims.

Trump pushed Powell out. And, after days of prodding by advisers, he agreed to permit the General Services Administration to formally initiate the Biden transition — a procedural step that amounted to a surrender. Aides said this was the closest Trump would probably come to conceding the election.

Yet even that incomplete surrender was short-lived. Trump went on to falsely claim that he “won,” that the election was “a total scam” and that his legal challenges would continue “full speed ahead.” He spent part of Thanksgiving calling advisers to ask if they believed he really had lost the election, according to a person familiar with the calls. “Do you think it was stolen?” the person said Trump asked on the holiday.

But, his advisers acknowledged, that was largely noise from a president still coming to terms with losing. As November was coming to a close, Biden rolled out his Cabinet picks, states certified his wins, electors planned to make it official when the electoral college meets Dec. 14 and federal judges spoke out.

A simple and clear refutation of the president came Friday from a Trump appointee, when Judge Stephanos Bibas of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit wrote a unanimous opinion rejecting the president’s request for an emergency injunction to overturn the certification of Pennsylvania’s election results.

“Free, fair elections are the lifeblood of our democracy,” Bibas wrote. “Charges of unfairness are serious. But calling an election unfair does not make it so. Charges require specific allegations and then proof. We have neither here.”

For Trump, it was over.

“Not only did our institutions hold, but the most determined effort by a president to overturn the people’s verdict in American history really didn’t get anywhere,” said William A. Galston, chair of the governance studies program at the Brookings Institution. “It’s not that it fell short. It didn’t get anywhere. This, to me, is remarkable.”

‘There has to be a conspiracy’

Trump’s devolution into disbelief of the results began on election night in the White House, where he joined campaign manager Bill Stepien, senior advisers Jared Kushner and Jason Miller, and other top aides in a makeshift war room to monitor returns.

In the run-up to the election, Trump was aware of the fact — or likelihood, according to polls — that he could lose. He commented a number of times to aides, “Oh, wouldn’t it be embarrassing to lose to this guy?”

But in the final stretch of the campaign, nearly everyone — including the president — believed he was going to win. And early on election night, Trump and his team thought they were witnessing a repeat of 2016, when he defied polls and expectations to build an insurmountable lead in the electoral college.

Then Fox News called Arizona for Biden.

“He was yelling at everyone,” a senior administration official recalled of Trump’s reaction. “He was like, ‘What the hell? We were supposed to be winning Arizona. What’s going on?’ He told Jared to call [News Corp. Executive Chairman Rupert] Murdoch.”

Efforts by Kushner and others on the Trump team to persuade Fox to take back its Arizona call failed.

Trump and his advisers were furious, in part because calling Arizona for Biden undermined Trump’s scattershot plan to declare victory on election night if it looked as though he had sizable leads in enough states.

With Biden now just one state away from clinching a majority 270 votes in the electoral college and the media narrative turned sharply against him, Trump decided to claim fraud. And his team set out to try to prove it.

Throughout the summer and fall, Trump had laid the groundwork for claiming a “rigged” election, as he often termed it, warning of widespread fraud. Former chief of staff John F. Kelly told others that Trump was “getting his excuse ready for when he loses the election,” according to a person who heard his comments.

In June, during an Oval Office meeting with political advisers and outside consultants, Trump raised the prospect of suing state governments for how they administer elections and said he could not believe they were allowed to change the rules. All the states, he said, should follow the same rules. Advisers told him that he did not want the federal government in charge of elections.

Trump also was given several presentations by his campaign advisers about the likely surge in mail-in ballots — in part because many Americans felt safer during the pandemic voting by mail than in person — and was told they would go overwhelmingly against him, according to a former campaign official.

Advisers and allies, including Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), encouraged Trump to try to close the gap in mail-in voting, arguing that he would need some of his voters, primarily seniors, to vote early by mail. But Trump instead exhorted his supporters not to vote by mail, claiming they could not trust that their ballots would be counted.

“It was sort of insane,” the former campaign official said.

Ultimately, it was the late count of mail-in ballots that erased Trump’s early leads in Georgia, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and other battleground states and propelled Biden to victory. As Trump watched his margins shrink and then reverse, he became enraged, and he saw a conspiracy at play.

“You really have to understand Trump’s psychology,” said Anthony Scaramucci, a longtime Trump associate and former White House communications director who is now estranged from the president. “The classic symptoms of an outsider is, there has to be a conspiracy. It’s not my shortcomings, but there’s a cabal against me. That’s why he’s prone to these conspiracy theories.”

This fall, deputy campaign manager Justin Clark, Republican National Committee counsel Justin Riemer and others laid plans for post-election litigation, lining up law firms across the country for possible recounts and ballot challenges, people familiar with the work said. This was the kind of preparatory work presidential campaigns typically do before elections. Giuliani, Ellis and Powell were not involved.

This team had some wins in court against Democrats in a flurry of lawsuits in the months leading up to the election, on issues ranging from absentee ballot deadlines to signature-matching rules.

But Trump’s success rate in court would change considerably after Nov. 3. The arguments that began pouring in from Giuliani and others on Trump’s post-election legal team left federal judges befuddled. In one Pennsylvania case, some lawyers left the Trump team before Giuliani argued the case to a judge. Giuliani had met with the lawyers and wanted to make arguments they were uncomfortable making, campaign advisers said.

For example, the Trump campaign argued in federal court in Philadelphia two days after the election to stop the count because Republican observers had been barred. Under sharp questioning from Judge Paul S. Diamond, however, campaign lawyers conceded that Trump in fact had “a nonzero number of people in the room,” leaving Diamond audibly exasperated.

“I’m sorry, then what’s your problem?” Diamond asked.

‘How do we get to 270?’

In the days following the election, few states drew Trump’s attention like Georgia, a once-reliable bastion of Republican votes that he carried in 2016 but appeared likely to lose narrowly to Biden as late-remaining votes were tallied.

And few people attracted Trump’s anger like Gov. Brian Kemp, the state’s Republican governor, who rode the president’s coattails to his own narrow victory in 2018.

A number of Trump allies tried to pressure Raffensperger, the Republican secretary of state, into putting his thumb on the scale. Republican Sens. David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler — both forced into runoff elections on Jan. 5 — demanded Raffensperger’s resignation. Sen. Lindsey O. Graham (R-S.C.), a Trump friend who chairs the powerful Senate Judiciary Committee, called Raffensperger to seemingly encourage him to find a way to toss legal ballots.

But Kemp, who preceded Raffensperger as secretary of state, would not do Trump’s bidding. “He wouldn’t be governor if it wasn’t for me,” Trump fumed to advisers earlier this month as he plotted out a call to scream at Kemp.

In the call, Trump urged Kemp to do more to fight for him in Georgia, publicly echo his claims of fraud and appear more regularly on television. Kemp was noncommittal, a person familiar with the call said.

Raffensperger said he knew Georgia was going to be thrust into the national spotlight on Election Day, when dramatically fewer people turned out to vote in person than the Trump campaign needed for a clear win following a surge of mail voting dominated by Democratic voters.

But he said it had never occurred to him to go along with Trump’s unproven allegations because of his duty to administer elections. Raffensperger said his strategy was to keep his head down and follow the law.

“People made wild accusations about the voting systems that we have in Georgia,” Raffensperger said. “They were asking, ‘How do we get to 270? How do you get it to Congress so they can make a determination?’ ” But, he added, “I’m not supposed to put my thumb on the Republican side.”

Trump fixated on a false conspiracy theory that the machines manufactured by Dominion Voting Systems and used in Georgia and other states had been programmed to count Trump votes as Biden votes. In myriad private conversations, the president would find a way to come back to Dominion. He was obsessed.

“Do you think there’s really something here? I’m hearing . . . ” Trump would say, according to one senior official who discussed it with him.

Raffensperger said Republicans were only harming themselves by questioning the integrity of the Dominion machines. He warned that these kinds of baseless allegations could discourage Republicans from voting in the Senate runoffs. “People need to get a grip on reality,” he said.

More troubling to Raffensperger were the many threats he and his wife, Tricia, have received over the past few weeks — and a break-in at another family member’s home. All of it has prompted him to accept a state security detail.

“If Republicans don’t start condemning this stuff, then I think they’re really complicit in it,” he said. “It’s time to stand up and be counted. Are you going to stand for righteousness? Are you going to stand for integrity? Or are you going to stand for the wild mob? You wanted to condemn the wild mob when it’s on the left side. What are you going to do when it’s on our side?”

On Nov. 20, after Raffensperger certified the state’s results, Kemp announced that he would make a televised statement, stoking fears that the president might have finally gotten to the governor.

“This can’t be good,” Jordan Fuchs, a Raffensperger deputy, wrote in a text message.

But Kemp held firm and formalized the certification.

“As governor, I have a solemn responsibility to follow the law, and that is what I will continue to do,” Kemp said. “We must all work together to ensure citizens have confidence in future elections in our state.”

‘A hostile takeover’

On Nov. 7, four days after the election, every major news organization projected that Biden would win the presidency. At the same time, Giuliani stood before news cameras in the parking lot of Four Seasons Total Landscaping in Philadelphia, near an adult-video shop and a crematorium, to detail alleged examples of voter fraud.

The contrast that day between Giuliani’s humble, eccentric surroundings and Biden’s and Vice President-elect Kamala D. Harris’s victory speeches on a grand, blue-lit stage in Wilmington, Del., underscored the virtual impossibility of Trump’s quest to overturn the results.

Also that day, Stepien, Clark, Miller and Bossie briefed Trump on a potential legal strategy for the president’s approval. They explained that prevailing would be difficult and involve complicated plays in every state that could stretch into December. They estimated a “5 to 10 percent chance of winning,” one person involved in the meeting said.

Trump signaled that he understood and agreed to the strategy.

Around this time, some lawyers around Trump began to suddenly disappear from the effort in what some aides characterized as an attempt to protect their reputations. Former Florida attorney general Pam Bondi, who had appeared at a news conference with Giuliani right after the election, ceased her involvement after the first week.

“Literally only the fringy of the fringe are willing to do pressers, and that’s when it became clear there was no ‘there’ there,” a senior administration official said.

A turning point for the Trump campaign’s legal efforts came on Nov. 13, when its core team of professional lawyers saw the writing on the wall. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit in Philadelphia delivered a stinging defeat to Trump allies in a lawsuit trying to invalidate all Pennsylvania ballots received after Election Day.

The decision didn’t just reject the claim; it denied the plaintiffs standing in any federal challenge under the Constitution’s electors clause — an outcome that Trump’s legal team recognized as a potentially fatal blow to many of the campaign’s challenges in the state.

That is when a gulf emerged between the outlooks of most lawyers on the team and of Giuliani, who many of the other lawyers thought seemed “deranged” and ill-prepared to litigate, according to a person familiar with the campaign’s legal team. Some of the Trump campaign and Republican Party lawyers sought to even avoid meetings with Giuliani and his team. When asked for evidence internally for their most explosive claims, Giuliani and Powell could not provide it, the other advisers said.

Giuliani and his protegee, Ellis, both striving to please the president, insisted Trump’s fight was not over. Someone familiar with their strategy said they were “performing for an audience of one,” and that Trump held Giuliani in high regard as “a fighter” and as “his peer.”

Tensions within Trump’s team came to a head that weekend, when Giuliani and Ellis staged what the senior administration official called “a hostile takeover” of what remained of the Trump campaign.

On the afternoon of Nov. 13, a Friday, Trump called Giuliani from the Oval Office while other advisers were present, including Vice President Pence; White House counsel Pat Cipollone; Johnny McEntee, the director of presidential personnel; and Clark.

Giuliani, who was on speakerphone, told the president that he could win and that his other advisers were lying to him about his chances. Clark called Giuliani an expletive and said he was feeding the president bad information. The meeting ended without a clear path, according to people familiar with the discussion.

The next day, a Saturday, Trump tweeted out that Giuliani, Ellis, Powell and others were now in charge of his legal strategy. Ellis startled aides by entering the campaign’s Arlington headquarters and instructing staffers that they must now listen to her and Giuliani.

“They came in one day and were like, ‘We have the president’s direct order. Don’t take an order if it doesn’t come from us,’ ” a senior administration official recalled.

Clark and Miller pushed back, the official said. Ellis threatened to call Trump, to which Miller replied, “Sure, let’s do this,” said a campaign adviser.

It was a fiery altercation, not unlike the many that had played out over the past four years in the corridors of the West Wing. The outcome was that Giuliani and Ellis, as well as Powell — the “elite strike force,” as they dubbed themselves — became the faces of the president’s increasingly unrealistic attempts to subvert democracy.

The strategy, according to a second senior administration official, was, “Anyone who is willing to go out and say, ‘They stole it,’ roll them out. Rudy Giuliani, Jenna Ellis, Sidney Powell. Send [former acting director of national intelligence] Ric Grenell out West. Send [American Conservative Union Chairman] Matt Schlapp somewhere. Just roll everybody up who is willing to do it into a clown car, and when it’s time for a press conference, roll them out.”

Trump and his allies made a series of brazen legal challenges, including in Nevada, where conservative activist Sharron Angle asked a court to block certification of the results in Clark County, by far the state’s most populous county, and order a wholesale do-over of the election.

Clark County Judge Gloria Sturman was incredulous.

“How do you get to that’s sufficient to throw out an entire election?” she said. She noted the practical implications of failing to certify the election, including that every official elected on Nov. 3 would be unable to take office in the new year, including herself.

Sturman denied the request. Not only was there no evidence to support the claims of widespread voter fraud, she said, but “as a matter of public policy, this is just a bad idea.”

‘A flavor of the truth’

As Trump’s legal challenges failed in court, he employed another tactic to try to reverse the result: a public pressure campaign on state and local Republican officials to manipulate the electoral system on his behalf.

“As was the case throughout his business career, he viewed the rules as instruments to be manipulated to achieve his chosen ends,” said Galston of the Brookings Institution.

Trump’s highest-profile play came in Michigan, where Biden was the projected winner and led by more than 150,000 votes. On Nov. 17, Trump called a Republican member of the board of canvassers in Wayne County, which is where Detroit is located and is the state’s most populous county. After speaking with the president, the board member, Monica Palmer, attempted to rescind her vote to certify Biden’s win in Wayne.

Then Trump invited the leaders of Michigan’s Republican-controlled state Senate and House to meet him at the White House, apparently hoping to coax them to block certification of the results or perhaps even to ignore Biden’s popular-vote win and seat Trump electors if the state’s canvassing board deadlocked. Such a move was on shaky legal ground, but that didn’t stop the president from trying.

Republican and Democratic leaders, including current and former governors and members of Congress, immediately launched a full-court press to urge the legislative leaders to resist Trump’s entreaties. The nonpartisan Voter Protection Program was so worried that it commissioned a poll to find out how Michiganders felt about his intervention. The survey found that a bipartisan majority did not like Trump intervening and believed that Biden won the state.

House Speaker Lee Chatfield and Senate Majority Leader Mike Shirkey said they accepted the invitation as a courtesy and issued a joint statement immediately after the meeting: “We have not yet been made aware of any information that would change the outcome of the election in Michigan.”

A person familiar with their thinking said they felt they could not decline the president’s invitation — plus they saw an opportunity to deliver to Trump “a flavor of the truth and what he wasn’t hearing in his own echo chamber,” as well as to make a pitch for coronavirus relief for their state.

There was never a moment when the lawmakers contemplated stepping in on Trump’s behalf, because Michigan law does not allow it, this person said. Before the trip, lawyers for the lawmakers told their colleagues in the legislature that there was nothing feasible in what Trump was trying to do, and that it was “absolute crazy talk” for the Michigan officials to contemplate defying the will of the voters, this person added.

Trump was scattered in the meeting, interrupting to talk about the coronavirus when the lawmakers were talking about the election, and then talking about the election when they were talking about the coronavirus, the person said. The lawmakers left with the impression that the president understood little about Michigan law, but also that his blinders had fallen off about his prospects for reversing the outcome, the person added.

No representatives from Trump’s campaign attended the meeting, and advisers talked Trump out of scheduling a similar one with Pennsylvania officials.

The weekend of Nov. 21 and on Monday, Nov. 23, Trump faced mounting pressure from Republican senators and former national security officials — as well as from some of his most trusted advisers — to end his stalemate with Biden and authorize the General Services Administration to initiate the transition. The bureaucratic step would allow Biden and his administration-in-waiting to tap public funds to run their transition, receive security briefings and gain access to federal agencies to prepare for the Jan. 20 takeover.

Trump was reluctant, believing that by authorizing the transition, he would in effect be conceding the election. Over multiple days, White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows, Cipollone and Jay Sekulow, one of the president’s personal attorneys, explained to Trump that the transition had nothing to do with conceding and that legitimate challenges could continue, according to someone familiar with the conversations.

Late on Nov. 23, Trump announced that he had allowed the transition to move forward because it was “in the best interest of our Country,” but he kept up his fight over the election results.

The next day, after a conversation with Giuliani, Trump decided to visit Gettysburg, Pa., on Nov. 25, the day before Thanksgiving, for a news conference at a Wyndham Hotel to highlight alleged voter fraud. The plan caught many close to the president by surprise, including RNC Chairwoman Ronna McDaniel, three officials said. Some tried to talk Trump out of the trip, but he thought it was a good idea to appear with Giuliani.

A few hours before he was scheduled to depart, the trip was scuttled. “Bullet dodged,” said one campaign adviser. “It would have been a total humiliation.”

That afternoon, Trump called in to the meeting of GOP state senators at the Wyndham, where Giuliani and Ellis were addressing attendees. He spoke via a scratchy connection to Ellis’s cellphone, which she played on speaker. At one point, the line beeped to signal another caller.

“If you were a Republican poll watcher, you were treated like a dog,” Trump complained, using one of his favorite put-downs, even though many people treat dogs well, like members of their own families.

“This election was lost by the Democrats,” he said, falsely. “They cheated.”

Trump demanded that state officials overturn the results — but the count had already been certified. Pennsylvania’s 20 electoral votes will be awarded to Biden.

From the conservative National Review:

President Trump said the other day that he’d leave office if he loses the vote of the Electoral College on December 14.

This is not the kind of assurance presidents of the United States typically need to make, but it was noteworthy given Trump’s disgraceful conduct since losing his bid for reelection to Joe Biden on November 3.

Behind in almost all the major polls, Trump stormed within a hair’s breadth in the key battlegrounds of winning reelection, and his unexpectedly robust performance helped put Republicans in a strong position for the post-Trump-presidency era. This is not nothing. But the president can’t stand to admit that he lost and so has insisted since the wee hours of Election Night that he really won — and won “by a lot.”

There are legitimate issues to consider after the 2020 vote about the security of mail-in ballots and the process of counting votes (some jurisdictions, bizarrely, take weeks to complete their initial count), but make no mistake: The chief driver of the post-election contention of the past several weeks is the petulant refusal of one man to accept the verdict of the American people. The Trump team (and much of the GOP) is working backwards, desperately trying to find something, anything to support the president’s aggrieved feelings, rather than objectively considering the evidence and reacting as warranted.

Almost nothing that the Trump team has alleged has withstood the slightest scrutiny. In particular, it’s hard to find much that is remotely true in the president’s Twitter feed these days. It is full of already-debunked claims and crackpot conspiracy theories about Dominion voting systems. Over the weekend, he repeated the charge that 1.8 million mail-in ballots in Pennsylvania were mailed out, yet 2.6 million were ultimately tallied. In a rather elementary error, this compares the number of mail-ballots requested in the primary to the number of ballots counted in the general. A straight apples-to-apples comparison finds that 1.8 million mail-in ballots were requested in the primary and 1.5 million returned, while 3.1 million ballots were requested in the general and 2.6 million returned.

Flawed and dishonest assertions like this pollute the public discourse and mislead good people who make the mistake of believing things said by the president of the United States.

Elected Republicans have generally taken the attitude that the president should be able to have his day in court. It’s his legal right to file suits, of course, but he shouldn’t pursue meritless litigation in Hail Mary attempts to get millions of votes tossed out. This is exactly what he’s been doing, it’s why reputable GOP lawyers have increasingly steered clear, and it’s why Trump has suffered defeat after defeat in court.

In its signature federal suit in Pennsylvania, the Trump team argued that it violated the equal-protection clause of the U.S. Constitution for some Pennsylvania counties to let absentee voters fix or “cure” their ballots if they contained an error while other counties didn’t. It maintained that it was another constitutional violation for Trump election observers not to be allowed in close proximity to the counting of ballots. On this basis, the Trump team sought to disqualify 1.5 million ballots and bar the certification of the Pennsylvania results or have the Pennsylvania General Assembly appoint presidential electors.

By the time the suit reached the Third Circuit, it had been whittled down to a relatively minor procedural issue (whether the Trump complaint could be amended a second time in the district court). The Trump team lost on that question, and the unanimous panel of the Third Circuit (in an opinion written by a Trump appointee) made it clear that the other claims lacked merit as well. It noted that the suit contained no evidence that Trump and Biden ballots or observers were treated differently, let alone evidence of fraud. Within reason, it is permissible for counties to have different procedures for handling ballots, and nothing forced some counties to permit voters to cure flawed absentee ballots and others to decline to do so.

Not that it mattered. The court pointed out that the suit challenged the procedures to fix absentee ballots in seven Democratic counties, which don’t even come close to having enough cured ballots to change the outcome in the state; the counties might have allowed, at most, 10,000 voters to fix their ballots, and even if every single one of them voted for Biden, that’s still far short of Biden’s 80,000-plus margin in the state.

The idea, as the Trump team stalwartly maintains, that the Supreme Court is going to take up this case and issue a game-changing ruling is fantastical. Conservative judges have consistently rejected Trump’s flailing legal appeals, and the justices are unlikely to have a different reaction.

Trump’s most reprehensible tactic has been to attempt, somewhat shamefacedly, to get local Republican officials to block the certification of votes and state legislatures to appoint Trump electors in clear violation of the public will. This has gone nowhere, thanks to the honesty and sense of duty of most of the Republicans involved, but it’s a profoundly undemocratic move that we hope no losing presidential candidate ever even thinks of again.

Getting defeated in a national election is a blow to the ego of even the most thick-skinned politicians and inevitably engenders personal feelings of bitterness and anger. What America has long expected is that losing candidates swallow those feelings and at least pretend to be gracious. If Trump’s not capable of it, he should at least stop waging war on the outcome.

The Reality TV president wants to do a grande finale…we just want him out.

President Trump is considering a made-for-TV grand finale: a White House departure on Marine One and final Air Force One flight to Florida for a political rally opposite Joe Biden’s inauguration, sources familiar with the discussions tell Axios.

Why it matters: The former network star is privately discussing using his waning powers as commander in chief to order up the exit he wants after dissing Biden by refusing to concede the election, welcome him to the White House or commit to attending his inauguration.

The big picture: The Trump talk could create a split-screen moment: the outgoing president addressing a roaring crowd in an airport hangar while the incoming leader is sworn in before a socially distanced audience outside the Capitol, as NBC News first reported.

- Immediately announcing he is running for re-election in 2024 would set up four years of Trump playing Biden’s critic-in-chief.

- The visual also would embody the vast difference in the two leaders’ approaches to the pandemic.

- And flying off from the South Lawn before landing in Florida would let Trump escape protests, the normal pleasantries of welcoming the incoming president to the White House — and sitting there while Biden takes the oath of office.

The Trump campaign declined to comment on his plans.

This is an article from 2016. I never saw it until now. It’s remarkable.

Donald Trump’s made-up coat-of-arms reveals his electoral strategy: Never concede

Donald Trump was certainly not the first American child of immigrants to try to cobble together a more interesting backstory once he got to Europe.

When the real estate developer announced plans for a golf resort in Aberdeen, Scotland, he began promoting the project with a coat-of-arms that someone in the Trump Organization designed: a shield with three chevrons and two stars, with a helmet above the shield and a crest of a lion waving a flag (a remarkable feat for an animal that lacks opposable thumbs). I know how to describe the various parts of the crest because Scotland takes its coats-of-arms very seriously. So seriously that one must register a coat-of-arms (which applies only to an individual, not a family), and the cost of registration increases as you add various elements (like that helmet). Trump was using an unauthorized coat-of-arms, and Scotland got mad.

Let’s note that Trump is not entirely Scottish. As TV host John Oliver made famous last year, Trump’s family name was originally Drumpf, via his paternal grandfather, who immigrated from Germany. Trump’s mother was born in Scotland, but she was a MacLeod by birth. The MacLeods have a crest, but it shows a cow surrounded by a belt or something and, critically, doesn’t include the word Trump.

So Trump made his own coat-of-arms (which is different than a crest) and started using it, and Scotland got upset and demanded he stop using it until it was registered. Trump registered the coat-of-arms, and four years later (such things don’t progress rapidly, it seems) was granted the right to use it.

But we’re not here today to talk about Trump’s fight to use a made-up coat-of-arms to make his golf course seem fancier. We’re here to talk about the etymology of words derived from Latin.

A spokesperson for Trump International described the coat-of-arms to the New York Post when it was approved in 2012.

Three chevronels are used to denote the sky, sand dunes and sea — the essential components of the [golf resort] site — and the double-sided eagle represents the dual nature and nationality of Trump’s heritage. The eagle clutches golf balls, making reference to the great game of golf, and the motto ‘Numquam Concedere’ is Latin for ‘Never Give Up’ — Trump’s philosophy.

It is funny to think of a two-headed eagle trying to hold a golf ball.

It is funnier, though, to realize that the primary focus of the past three weeks of Trump’s presidential campaign – if he loses, it’s probably because the vote is rigged and he won’t accept the results – is right there in that golfing-eagle coat-of-arms. Numquam concedere . Never give up. Or, even better, “never concede.” The verb to concede is derived from concedere . A bit on the nose.

Well, except that “never concede” is not the best translation of numquam concedere . Gareth Williams, who teaches Latin poetry at Columbia University, suggested in an email that the better translation is “never give in.” But, still!

If you go to the website for Trump’s course in Scotland, you can see the coat-of-arms in all of its extravagance at the top-center of the page. The main page for Trump Golf uses a different crest, with a banner at the bottom reading “Trump” and only two chevrons for some reason. (Maybe it left out the sky?) When Trump bought a course in Ireland two years ago, planning to rebrand it as Trump International Golf Links, Ireland, he repurposed his Scottish coat-of-arms, putting “Ireland” under it instead of “Scotland.”

Never give up a good brand logo once you’ve paid the money to get it approved. Never concede.

Trump tells allies he will run in 2024, but hints he may back out

In calls to allies, Trump has been asking how to navigate the next two years and floated a possible trip to the Middle East.

Donald Trump doesn’t need to run for president again. He just needs everyone to think he is.

The president’s recent discussions with those around him reveal that he sees his White House comeback deliberations as a way to earn the commodity he needs most after leaving office: attention.

The president has spent days calling a dozen or more allies to ask what they think he needs to do over the next two years to “stay part of the conversation,” according to two people, including one who spoke to the president. And while Trump has told allies he plans to run for president again, he has also indicated he could back out in two years if he determines he’ll have a tough time winning, said three people familiar with the discussions.

Essentially, at this point, Trump appears just as interested in people talking about a Trump 2024 campaign as he is in actually launching a real campaign, even if he may ultimately turn his flirtation into a serious bid, according to interviews with 11 Republicans who worked for Trump or helped in his two races.

Formally running for president would mean a lot of things aides say Trump doesn’t want to deal with: financial disclosure forms, building campaign infrastructure, the possibility of losing again. But simply teasing a presidential run — without actually filing the paperwork or erecting a campaign — gets Trump the attention he needs for the next two years.

Attention will help sustain his business, parts of which lost millions of dollars while he was in office. Attention will help pay off his debts, which will need to be paid off in the coming years. Attention will help discredit his investigators, who are examining whether Trump illegally inflated his assets.

It’s a strategy Trump has used before. Prior to his 2016 run, Trump expressed interest in at least four different presidential bids spanning all the way to the late 1980s, only to ultimately back out.

“Trump has probably no idea if he will actually run, but because he only cares about himself and his association with the party has only been about his ambitions rather than what it stands for, he will try to freeze the field and keep as many people on the sidelines,” said a former White House aide. “Just for the sake of keeping his options open and, yes, keeping the attention all for himself.”

Trump hasn’t announced his candidacy yet in part because he won’t acknowledge he lost, falsely asserting widespread voter fraud gave the race to President-elect Joe Biden. On Monday, electors will meet in states across the country to officially cast their votes, a move expected to cement Biden’s win and prompt more Republicans to accept the victory.

That vote will train more focus on Trump’s future plans. Many in the MAGA base and even some prospective 2024 Republican presidential hopefuls have already thrown their support behind another Trump White House bid.

“There’s nobody really better than him to carry the torch,” said John Fredericks, a conservative radio host who served on the Trump campaign’s 2020 advisory committee.

In his calls to allies, Trump has been asking them specifically how he can campaign for four years, and soliciting advice on how to navigate the first two years. He has talked about traveling to the Middle East, a region where he would be well-received, according to the two people familiar with the calls. The visit would allow him to promote his policies there, including agreements his administration helped negotiate to normalize relations between Israel and several Arab nations.

Among those he’s called are Fox News host Sean Hannity, former White House communications director Bill Shine, longtime allies Corey Lewandowski and David Bossie and former U.S. Ambassador to Germany Ric Grenell, according to one of people familiar with the calls. None of these people are dissuading him about running, but, according to the person, Trump has already dismissed concerns from those who think it’s a bad idea.

Some allies have privately urged Trump to announce he is running on Inauguration Day – as he did in 2017 — to try to take attention away from Biden and satisfy Trump’s need for attention. But Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law and top aide, and Bill Stepien, Trump’s 2020 campaign manager, are advising him to take his time to announce, according to two people familiar with the discussions.

The Trump campaign declined to comment. The White House and those Trump called didn’t respond to messages.

“He’s going to announce,” according to the person. “It’s not a question of whether he will announce. The question is when he is going to announce.”

Trump’s anticipated announcement is nearly unprecedented. Most recent former presidents have shied away from the limelight after leaving office, in part to allow their successor to govern. Several presidents have tried to secure a second non-consecutive term, but Grover Cleveland is the only one to succeed, mounting a 1892 comeback after being voted out of office in 1888.

“He will be astounded at how irrelevant a president becomes after losing reelection. Ask Jimmy Carter. Ask George H.W. Bush,” said presidential historian Michael Beschloss. “They become aware they are unable to affect things the way they had become accustomed to.”

Hoping to stave off that irrelevancy, Trump is expected to start promoting his candidacy immediately after leaving office, basing his early messaging on the unfounded allegation the last election was stolen from him.

If Trump is just technically exploring a potential candidacy, he doesn’t have to register as a candidate, even if he conducts polling, travels and calls potential supporters, according to the Federal Elections Commission and election lawyers. But if he makes declarative statements about running, purchases campaign ads or spends more than $5,000 on an actual campaign, he would have to register, they added.

“I think it’s important for Trump to boldly telegraph to the public that this election was a sham, that it can never happen again, and that he will lead the opposition for the next four years, including demanding election reforms,” a senior Trump campaign official said.

Meanwhile, Biden has been building up his White House team, largely ignoring Trump’s remarks about the 2020 and 2024 races.

“The oxygen of his life is attention,” said Steve Schale, who ran Unite the Country, a super PAC that supported Biden’s candidacy. “I’m sure that not being on the news every day is a terrifying prospect to him. … I would not be surprised if he announced because he needs it.”

A former Trump aide, who doesn’t want Trump to run a third time, said the early launch would be all about “ego.”

Trump biographer Michael D’Antonio agreed: “He’s not interested in running anything,” D’Antonio said. “He’s just interested in getting the attention.”

Some Republicans fear Trump’s boasts about running again will crowd out the 2024 Republican field, including three people who worked in his administration: Vice President Pence, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and former United Nations Ambassador Nikki Haley, preventing the party from evolving beyond him.

The GOP is torn between conservatives who support Trump and moderates who are eager to distance themselves, but have held back due to fears over backlash from Trump’s base. Fifty three percent of Republicans said they would vote for Trump in a primary in 2024, according to a POLITICO and Morning Consult poll in late November.

In the interviews of the 11 Republicans who worked for Trump or helped in his two races, only three would commit to supporting him this early.

Some Republicans complain that Trump’s early candidacy could take money and attention from other candidates in 2022, 2021 and, more immediately, the pair of Senate runoffs in Georgia next month that will determine which party controls the upper chamber.

“Donald Trump has put himself ahead of the party and the country,” said Dan Eberhart, a major Republican donor. “I am shaking my head. The speed with which Trump has rearmed post the general election makes me blush. There is no off-season anymore.”

If Trump formally files paperwork to run, he could begin raising money for his race immediately. If he announces informally, he could continue to raise money for his new political organization, Save America PAC, which he created days after Biden was projected to win.

Already, he’s raised tens of millions of dollars for the leadership PAC, the type of organization popular with both parties but one long derided by ethics groups because of the few restrictions on how the money they raise can be spent.

A Republican who speaks to the president said Trump and his aides are discussing whether he should delay his official candidacy because of requirements to file financial disclosure reports on his businesses.

The Trump Organization is presumed to have lost millions of dollars during the coronavirus outbreak just before Trump has to pay back $421 million in loans that he guaranteed, much of it to foreign creditors, according to a New York Times examination of Trump’s personal and business tax returns.

Meanwhile, New York investigators are examining whether Trump improperly inflated assets, evaded taxes and paid off women alleging affairs in violation of campaign finance laws.

The Republican who speaks to the president said they would advise Trump to wait to announce any candidacy, not because of his legal troubles but because he might be more desirable as a candidate.

“My advice would be to let time go by,” the person said. “If he allows time to go by, then he will allow people to miss him."

The Biden Transition

- Joe Biden may be the new president-elect — but with President Donald Trump continuing to challenge the results and Senate control up still up for grabs, the story of the election is far from over.

Biden’s plans

- Biden racks up votes as Electoral College meets to formalize 2020 results.

- Biden’s Cabinet rollouts hit bumps in the road.

- Biden’s promised Cuba reset has big tech implications.

- Trump is leaving Biden with a political landmine on human rights.

Trump and the GOP

- Trump tells allies he will run in 2024, but hints he may back out.

- Trump unleashed an army of sore losers.

- The White House is making big changes at the Pentagon — but Biden can reverse them.

- America First super PAC fights for relevance as Trump takes fundraising reins.

Joe Biden is now president and Trump just fired Barr by tweet.

This interim - Lame Duck period would be rocky at best…and good riddance to Barr, who salvaged very little integrity after his shameful performance as AG.

Guess Barr perhaps wants to NOT have to get involved with a bunch of frivolous pardons…who knows?

Buh Bye Felicia