Whatever happens, McConnell is once again showing that all of the GOP’s screaming about bipartisanship is just noise, as they steamroll ahead to a sham trial.

McConnell’s win on impeachment trial procedure was months in the making

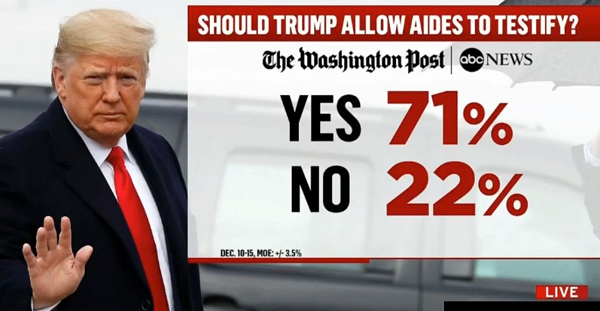

Chuck Schumer demanded Tuesday morning that Republicans allow witnesses to testify during President Donald Trump’s impeachment trial. But Mitch McConnell already knew he had the votes to roll over his adversary.

It took just a few hours for McConnell and Senate GOP leaders to clinch a final whip count in support of moving forward with a trial framework that ignores Democratic requests. And all 53 Republicans — even moderates such as Susan Collins of Maine, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, and Mitt Romney of Utah — have agreed to the majority leader’s proposal, according to senators involved in the process.

McConnell had spent months cultivating his caucus to get to this point. And after McConnell told his colleagues of his plans at the GOP’s weekly lunch, he went out and told a media horde the same.

“We have the votes,” McConnell declared, meaning Republicans can start the Trump trial with no Democratic input once Speaker Nancy Pelosi sends over the articles of impeachment.

Under the tentative rules package, which is the same as those used in President Bill Clinton’s 1999 Senate trial, the House will be allowed to present its case against Trump and then the president’s defense team will respond. At that point, McConnell or any GOP senator could move to end the trial and call for a final vote on the charges against Trump. Or Democrats could try to seek witness testimony or the introduction of new documentary evidence. It will be up to a majority of the Senate to decide.

Yet for McConnell and Trump, the victory is securing a path to getting the trial started. For both the Senate majority leader, whose majority is endangered, and a president facing reelection in nearly 10 months, the overwhelming concern is kicking off the proceeding so they can hurry up and acquit Trump.

McConnell’s raw exercise of power is also a setback for Schumer, who had pressured Republicans for weeks to allow witnesses and new evidence to be introduced but ultimately had little leverage if McConnell could keep his caucus together. The minority leader warned that the decision would come back to haunt Republicans, especially those who go before voters in November with Trump on the top of the ballot.

“Make no mistake: On the question of witnesses and documents, Republicans may run, but they can’t hide,” Schumer said on the Senate floor. “There will be votes at the beginning [of the trial] on whether to call the four witnesses we’ve proposed and subpoena the documents we’ve identified. America, and the eyes of history, will be watching what my Republican colleagues do.”

As with much of what McConnell does, he laid the groundwork for Tuesday’s maneuver over several months. Using a series of presentations starting in the fall, McConnell began gently guiding his members toward the Clinton impeachment rules, with special attention given to his members up for reelection this cycle.

Collins wouldn’t delve into the details, but she said she’d had several conversations with McConnell. And while she had hoped Schumer and McConnell could reach an agreement to establish trial parameters like past Senate leaders, “it doesn’t appear that’s going to happen.”

While Schumer may get the last laugh if McConnell’s impeachment strategy costs the GOP the Senate, in the short term, his unceasing demand to hear from key administration witnesses and subpoena administration documents appears to have annoyed Collins and helped drive the Republican Conference together.

“I don’t think Chuck Schumer is very interested in my opinion since he’s just launched a website in Maine and just committed an additional $700,000 in additional negative advertising from the Majority Forward PAC,” Collins groused about Democrats’ drive to deny her a fifth term in November. “I don’t think he’s really very interested in doing anything but trying to defeat me by telling lies to the people of Maine. And you can quote me on that.”

For her part, Murkowski had gone radio silent over the holiday break to spend time with her family. On Monday evening, she met privately with McConnell to discuss impeachment and the potential U.S. military conflict with Iran.

“It was not an effort to ‘get my vote.’ The leader and I had exchanged phone calls over the Christmas holiday and I know this is going to shock you, but I took family time. I did!” Murkowski said in an interview. On Monday “he was checking in with me and I needed to check in with him too. … I was able to share with him some of my views.”

Winning over Collins and Murkowski is particularly notable because both senators had expressed discomfort with McConnell’s vows to coordinate closely with the White House on the impeachment trial .

Romney also hadn’t talked to McConnell since December — but the Utah Republican had already studied the Clinton impeachment trial with his staff and come to the conclusion it showed the best way forward.

However, unlike other Republicans, Romney is open to supporting motions to hear from witnesses, including former national security adviser John Bolton, indicating McConnell still has work to do to keep Trump’s acquittal on the fast track.

“There’s been no lobbying towards me in that regard. The Clinton process — I met with my team and gave it consideration,” Romney said. It “allows for a vote to determine whether or not we have witnesses after we have opening arguments. And that pathway will be available to us.”

Throughout his tenure running the Senate — which began two years before Trump’s presidency — McConnell has operated with a razor-thin majority and overwhelming Democratic opposition to everything he’s tried to do. So McConnell appeals only to Republicans on most issues, figuring that getting 51 votes, rather than 60, is his goal.

McConnell’s attempts to overturn Obamacare failed by the narrowest of margins in 2017, yet he was able to push through Trump’s tax cut in 2017 using parliamentary procedures that allowed the Senate to approve the measure on a party-line vote.

McConnell used the “nuclear option” to allow Republicans to unilaterally change Senate rules on nominations so Trump could put Neil Gorsuch on the Supreme Court that year as well. And that was followed by the intensely bitter struggle over Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the high court in 2018, a battle that remains seared in the minds of senators from both parties, especially those like Collins up for reelection this year.

Democrats claim Pelosi’s decision to withhold the impeachment articles for several weeks increased scrutiny on the question of whether the Senate would conduct a fair trial on charges that Trump abused his power and obstructed Congress in the Ukraine saga.

But it also appeared to backfire with Republicans. With Trump and McConnell both repeatedly bashing Pelosi and Schumer for the tactic, Republicans said it made it easier to persuade their vulnerable members to unify and endorse the Clinton impeachment trial rules.

“I think as the last few weeks have developed, it made the impeachment process from the House look more and more partisan all the time,” said Sen. Roy Blunt of Missouri, the No. 4 Senate Republican.

“We have a lot of people who weren’t here in ’99,” Senate Majority Whip John Thune added. “Making sure it’s an open and fair process is what’s important to our folks. A lot of our members just don’t want to get the label that the House members had about it being a rigged sham partisan process.”

Story Continued Below

Trump and White House officials were pleased by McConnell’s announcement Tuesday.

“We are heartened that we have a process now in place that allows us to begin as quickly as possible that allows us to make a full explanation of the facts against the false charges from the House,” said Eric Ueland, White House legislative affairs director, who sat in on the Senate Republican Conference meeting.

Democrats decried McConnell’s decision to move ahead without really seeking a bipartisan deal, accusing him of hurting the Senate as an institution over the long run to achieve short-term political goals.

“That’s what he’s done his whole career. He’s been an opportunist,” Sen. Sherrod Brown of Ohio fumed. “I’m not surprised he says anything. I’m not surprised he acts this way.”