By mid November, we should have results for the Presidency. The things that a sitting president might have going for him are now off the table, aside from incumbency. T’s solid with his base

yet his unfavorables are about 51%.

Aside from the 6 battleground states, and even with FL in a dead heat, the conditions within which T could win would include - a better economy, and no pandemic. But these two items are not going away anytime soon. One of the Republican strategiest Stuart Stevens, thought that if T could give an ‘apology’ for his handling of the pandemic, then people might feel better towards him. Here we have the rock and hard place and VERY FAVORABLE to the Dems, despite the circumstances…T will NEVER APOLOGIZE.

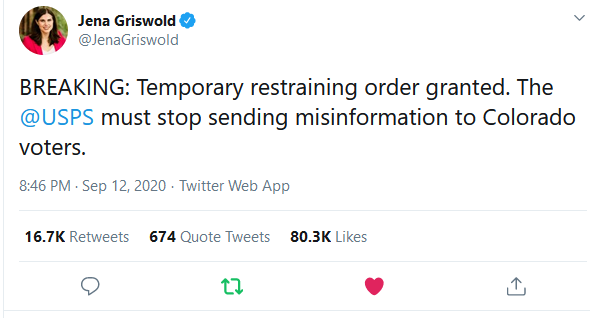

So the other factors that T could harness - scare and fearmonger the country, divide and conquer, prevent voting, have social media and servers upended by Russia and friends, and invasive cheating at the polls which T and his people (if T wins) will try to make stick.

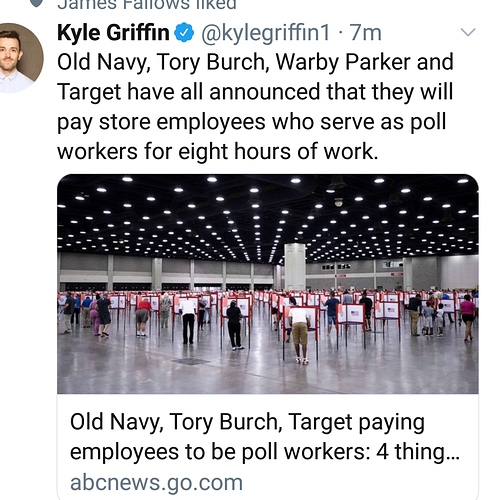

So no sure path to victory for anyone. But we do have an energized pack of voters out there to get out the vote.

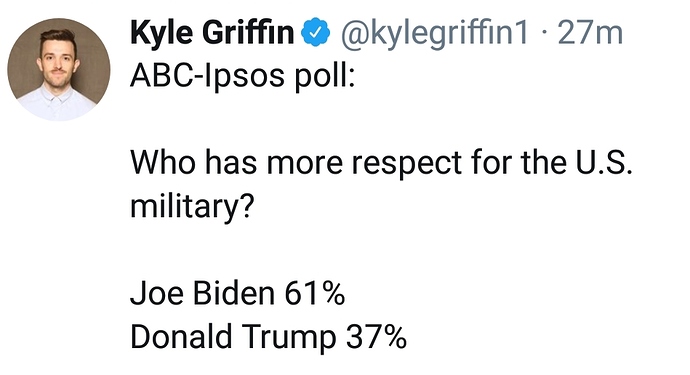

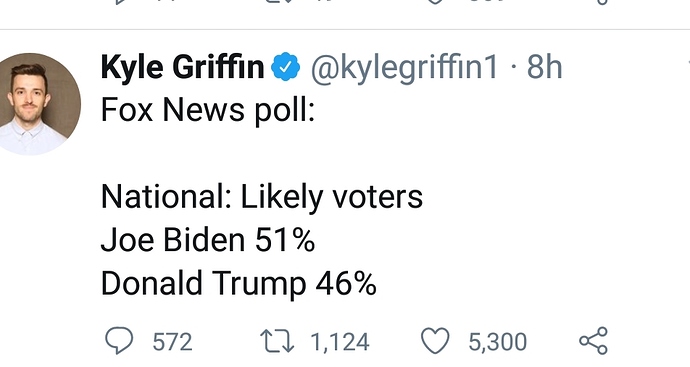

The professionals who remain at Trump reëlection headquarters are, with fewer than sixty days until the election, faced with a challenging set of statistics. For months, Joe Biden has led in national polls by at least seven percentage points. In order to win the Electoral College, Trump would need to beat Biden in about half of six swing states: Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, North Carolina, Florida, and Arizona. He trails Biden in all of them, though the margin in North Carolina and Florida is under two per cent. About forty-two per cent of Americans approve of the job he has done as President, a number that has remained fairly constant throughout his Presidency, but fifty-four per cent now disapprove, which puts him behind the ratings of Barack Obama, George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and Ronald Reagan at similar points in their reëlection campaigns—though well ahead of George H. W. Bush and Jimmy Carter. In other words, Trump looks likely to be either the least popular incumbent to win reëlection in the modern polling era or the most popular one to lose it.

To a younger generation of Republican consultants—those who have made their careers in the rancorous twenty-first century, when there have been sharp partisan divisions and few swing voters—those numbers don’t look so bad. The President, they point out, has consolidated his support among Republicans, roughly ninety per cent of whom say they support him. Nearly every poll that has asked voters whom they trust to manage the economy has found a preference for Trump over Biden, even polls that have Biden up by ten points—which suggests that any skeptical Republicans and independents might be persuaded to vote for Trump because of their perceived self-interest. Then, too, almost all of Trump’s decline has taken place among white voters. Among Latinos—a crucial electoral coalition in the swing states of Florida and Arizona—Trump’s position has held steady and may even have strengthened. Last month, a Public Religion Research Institute poll put his approval rating among Latinos in 2020 at thirty-six per cent, eight points ahead of the percentage of Latino voters that exit polls found he won in 2016. More ominously for Democrats, a recent survey of Florida Hispanic voters found Biden polling eleven points behind Hillary Clinton’s exit-poll results in 2016.

But even these strengths look more suspect on closer examination. They do not, for one thing, account for the immense suffering of the coronavirus pandemic, in which more than a hundred and ninety thousand Americans, many of them elderly, have died, and nearly thirty million people have begun receiving unemployment benefits. In 2016, Trump beat Clinton by about twenty points among senior citizens; now poll after poll finds that he leads Biden among seniors by only a few points. His strength on the economy may have been buoyed by the temporary unemployment benefits that Democrats demanded this spring, but those benefits have begun to expire, and Republicans have declined to renew them. The Census Bureau has been surveying households this summer and has asked families whether they expect to make their next month’s rent or mortgage payment. The responses put a lump in your throat. Worse numbers came midway through the summer, when in Florida, a state the President has to win, thirty-two per cent of respondents said that they had either missed their last housing payment or did not feel more than slightly confident that they would meet the next one.

Such numbers are almost unimaginably bleak. So it surprised me a little to notice, in poll after poll, that the public’s view of Trump’s handling of the virus isn’t so bad—it tends to track with his over-all approval ratings and to run five or ten points ahead of the public’s view of his response to the Black Lives Matter protests that followed George Floyd’s death. Most Republicans think that Trump is doing a fine job handling the pandemic, the universal crisis that he often seemed to want to minimize, but millions of Republicans disliked his response to demands for racial equity—an issue that he has deliberately sought to weaponize because he thought it might give him an advantage.

I mentioned this discrepancy to Charles Franklin, who runs the highly regarded Marquette Law School poll of Wisconsin voters. Franklin said that he had been looking into that issue: “Race is by far his worst evaluation, both in our data but, more importantly, in national data, and it has been for years.” Franklin found that most Trump voters in Wisconsin don’t support his message on race—not even close. “It is really a rural and a non-college phenomenon,” he said. In the suburbs of Milwaukee, as well as smaller cities, such as Green Bay and Appleton, “you have a Republican constituency that has never really wanted to embrace the negative messages on race that he focusses on and who are reluctant to see themselves as racist.” This pattern held true even after the violence in Portland and Kenosha. Trump spent days tweeting about “LAW & ORDER!” and claiming that liberal cities needed a strong hand. But the following week, polls suggested that this gambit hadn’t worked. Trump remained behind in every swing state, and an ABC poll found that fifty-five per cent of voters thought that Trump’s response to the protests made the situation worse, while only thirteen per cent thought that it made the situation better.

The raw statistical material is unpromising, but politics, at the highest level, is just talk. Is there a story that Trump could tell that would change something important about the election? Is there a way, in other words, that he might alchemize a likely loss into a win? Just before the Conventions, I called political consultants of every stripe—devoted and dissident Republicans, Democrats, progressives, and independents—to see whether they could imagine a winning path for the President. I found that, because of the pandemic, a striking number of them seemed to have spent the spring and summer far from Washington, holed up in their ski houses. (“Scout, no,” one former Presidential adviser instructed his dog, when I reached him in the Rockies. “No bark.”) But I also found that the isolation, and maybe the vistas, and maybe, too, the nearing possibility of a post-strategist politics, had caused them to focus on a single, pivotal question. Spin is such a weak, twentieth-century term for hard twenty-first-century realities: the pandemic, with more than a hundred and ninety thousand dead; the mass unemployment; the continuing patterns of unrest; the climate-catastrophe wildfires that have menaced Silicon Valley, the center of America’s twenty-first-century economy. Nevertheless, the consultants wondered, can all of this somehow be spun?

“I actually have a strong opinion about that,” Stuart Stevens, the Republican strategist who ran Mitt Romney’s Presidential campaign, said, when I reached him in Stowe, Vermont. “If you are thinking about what it takes for an unpopular incumbent to come back and win, there actually is a significant history. And I don’t know of any process that didn’t involve a mea culpa—an apology.”

In general, this is a losing tide for Republicans—the Party washing out from growing metro areas, leaving the suburbs open for Democrats. But Thompson and other Republicans working on congressional elections in 2020 believe that with the right message and a strong enough economy the demographic tide could be slowed. Maybe enough suburban Republicans could be persuaded to vote for their party’s candidate one last time, even though they dislike Trump. Thompson pointed to a couple of clear demographic opportunities. One was non-college-educated Latino men under fifty, who often have socially conservative views and low levels of social attachment—very similar characteristics to the white voters who had followed Trump into his coalition. “And when you ask them in polls, a lot of Hispanics describe themselves as white, even though political professionals say they are Hispanic,” Thompson said. A second, even bigger group is traditional suburban Republicans who do not regularly attend church; many are women in households attached to small businesses, whose social conservatism has helped them resist the general turn toward Democrats.

“And Trump doesn’t disgust them?” I asked.

Pollsters don’t ask about disgust, Thompson said. But those voters didn’t much like him.

One question that political consultants ask themselves a lot now is whether they should think about political talent differently than they have in the past. Biden’s ascendence suggests that not much has changed—that it is still important to channel the center of the country, that elections are still decided by the middle. But Trump’s triumphs make the opposite case, that elections now are just base versus base—trench warfare—and that they require a politician with more of a talent for incitement. This has been the story of much of American politics since the rise of the Tea Party, in 2010—of Trump but also of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, and of Scott Walker and Ted Cruz, all of whom evoke strong positive reactions within their own party and strong negative ones within the other, and who do not spend much time competing for a diminishing center.

…

Less than sixty days out from the election, Trump, unburdened by official campaign themes or facts, seems to be chasing a surprisingly large and protean coalition. At a Florida rally on Tuesday, Trump, who has long publicly doubted the science of climate change and championed coal mining and fracking, called himself “the great environmentalist” and called on Congress to expand protections against offshore drilling. Roe said that Trump might still be the Party’s best bet to reach conservative Latino and Black voters. He also pointed out that Trump has had more success at bringing white working-class voters into the Party than anyone since Reagan. Even in a pandemic, Trump’s crowds fill stadiums and overflow into parking lots. Roe said, “It’s a startling thing to say, but he’s the best crossover politician Republicans have.”