While the White House and lawmakers haggle over the terms of an emergency economic-stabilization package, Denmark has gone big—very, very big—to defeat the unprecedented challenge of the coronavirus.

This week, the Danish government told private companies hit by the effects of the pandemic that it would pay 75 percent of their employees’ salaries to avoid mass layoffs. The plan could require the government to spend as much as 13 percent of the national economy in three months. That is roughly the equivalent of a $2.5 trillion stimulus in the United States spread out over just 13 weeks. Like I said: very, very big.

This response might strike some as a catastrophically ruinous overreaction. Perhaps for Denmark, it will be. But we are at a fragile moment in American history. The U.S. faces the sharpest economic downturn in a century, and statistics that seem impossibly pessimistic one moment look positively optimistic hours later. In weeks—even days—Denmark’s aggressive response could be a blueprint for how the world can avoid another Great Depression.

To find out more, I corresponded with Flemming Larsen, a professor at the Center for Labor Market Research at Denmark’s Aalborg University, over two days of emails and an hour-long Skype call. The following interview blends those conversations, which have been edited for length and clarity.

Derek Thompson: Could you first give me a sense of what’s happening on the ground in Denmark? What do the streets look like?

Flemming Larsen: Denmark has nearly entirely closed down universities, schools, public institutions, restaurants, museums, cinemas. No assembly of more than 10 persons is allowed. The borders have been closed too.

Thompson: Denmark’s government has announced a very aggressive plan to help workers in the next few months. Tell me what it’s doing.

Larsen: Denmark’s government agreed to cover the cost of employees’ salaries at private companies as long as those companies do not fire people. If a company makes a notice saying that it has to either lay off 30 percent of their workers or fire at least 50 people, the state has agreed to take on 75 percent of workers’ salaries, up to $3,288 per month. (This would preserve the income for all employees earning up to $52,400 per year.)

The philosophy here is that the government wants companies to preserve their relationship with their workers. It’s going to be harder to have a strong recovery if companies have to spend time hiring back workers that have been fired. The plan will last for three months, after which point they hope things come back to normal.

Thompson: So the government is offering to pick up the tab for workers whose employment is threatened by the downturn. Couldn’t companies easily defraud the government and collect the money anyway?

Larsen: Maybe, but the workers compensated are not allowed to work in the period. Workers staying with the company do not receive the 75 percent compensation.

Thompson: Some American economists say the U.S. should copy Germany’s work-sharing plan, Kurzarbeit, in which workers’ hours are reduced and then the government takes on part of workers’ salaries. Is Denmark’s plan like that?

Larsen: Not exactly. In the German plan, the government and the employer share the cost of paying for work . Here, the government is paying companies for employees who are going home and not working . These workers are being paid a wage to do nothing. The government is saying: Lots of people are suddenly in danger of being fired. But if we have firing rounds, it will be very difficult to adapt later. This way, the company maintains their workforce under the crisis and people maintain their salaries. You are compensating people even though they have to go home.

Thompson: I think I understand you, and I’m going to try to summarize, but tell me if this summary is wrong: Denmark is putting the economy into the freezer for three months. You’re saying: We know that all these people won’t be able to work for the next few months. It’s inevitable. Rather than do rounds of firing followed by rounds of hiring, which will delay the recovery, let’s throw the whole economy into a deep freezer, and when the virus winds down we can thaw it out and almost everybody will still be with the company they worked for in January.

Larsen: That’s exactly it. We are freezing the economy. Because otherwise the government is afraid of the long-term damage that this will do to the entire system. The hope is that this will be over in three or four months, and then we can start up society again.

Thompson: What else is Denmark’s government proposing?

Larsen: There are a few things. To prevent the financial sector from shutting down, the state will guarantee 70 percent of new bank loans to companies. This will encourage more lending even in the case of more bankruptcies.

Also, people on unemployment benefits are put on pause. Typically, people have to go to meetings at job centers and make a certain number of job applications to receive jobless benefits. There are a lot of rules. But those rules are suspended for now. There are no requirements. The other part of the pause is that, while you can only be on unemployment benefits for two years in Denmark, people who pass that threshold will still receive benefits. Again, we are freezing everything.

Also, the state agreed to compensate companies for their fixed expenses, like rent and contract obligations, depending on their level of income loss. If they typically sell $1 million in a period, but now they can only sell $100,000, they lose 90 percent of their income. That will qualify them to receive large government help to cover fixed expenses.

Also, the spring payment of taxes for companies have been postponed until autumn, and all public employees will keep their salaries when sent home.

Thompson: This sounds incredibly bold and incredibly expensive. How much does the government expect this is going to cost?

Larsen: The cost is 287 billon DKK. [ Over email, we worked out that this is the equivalent of approximately 13 percent of the country’s GDP. In the U.S., that would be about $2.5 trillion. ]

Thompson: How does this response compare with what Denmark did during the global financial crisis in 2008?

Larsen: Back then, there was nothing at all at this scale. There was no huge amount of spending. The government was worried about public debt. There was a huge, long debate about whether Denmark should spend a lot of money at all. And Denmark had one of the highest increases in unemployment during the last crisis.

But today, the Danish economy is extremely strong. We have a huge surplus. We have a negative interest rate. There is a lot of public savings. So there is a lot of room to do this now. Also, the political environment has changed. We’ve tried to make higher investments in welfare spending in the last few years.

Thompson: It sounds like 10 years ago, there was a debate about stimulus. But today, everybody agrees that you just have to save the economy.

Larsen: Yes. They just want to save the economy. The philosophy is, if we don’t do it now, it will be more expensive to save the economy later. We’ve seen what the virus can do in Italy, in Spain. So I think people are very concerned. We are facing a huge, huge crisis.

Thompson: I have to admit that it’s rather jarring to hear about a country agreeing in a matter of days to do something this big. Your government could spend more than 10 percent of your GDP before July. Meanwhile, in the U.S., we’re still debating the size of government-signed checks that citizens might not receive for several months. There is a profound difference in both the speed and size of the government response.

Larsen: I have to say that the decision-making process in Denmark has been very extraordinary. We have 10 parties in Parliament. From the very left-wing to the really, really right-wing. And they all agree. There is nearly 100 percent consensus about this. And that’s really amazing. People are convinced that it’s wise to do this now.

Many of these policies are made as tripartite agreements between unions, employers’ associations, and the state. That’s because, in Denmark, most labor-market regulation is done by the unions and the employers’ associations. They regulate the labor market mainly through their own collective agreements. To make all this possible, you need the unions and employers’ associations to be a part of these agreements. That is very difficult. But they succeeded rapidly. In a matter of days, this was a signed agreement.

Thompson: Do you think it’s a good idea?

Larsen: I don’t know. Nobody knows for sure. This is unknown territory. I think it’s a good attempt. If you ruin people’s private lives and companies go bankrupt, it will take years to build this up again. So I think it’s a wise decision.

move on T’s part. And it is a complete shame.

move on T’s part. And it is a complete shame.

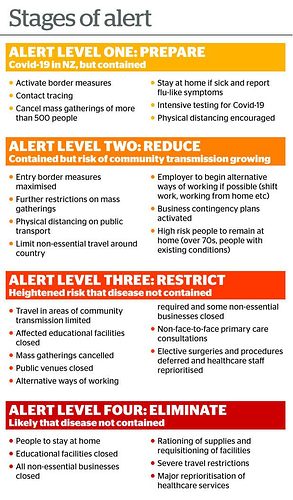

) said that a number of measures will also be taken to make sure people can cope, including no rent increases, and support for mortgage holders.

) said that a number of measures will also be taken to make sure people can cope, including no rent increases, and support for mortgage holders.