The virulent germ we now call the Spanish flu happened to strike at a diabolical moment in the history of politics and propaganda. The previous spring, in April of 1917, the United States entered the First World War, and President Woodrow Wilson launched a dubious campaign to shore up popular support and suppress criticism. He established the Committee on Public Information, whose chairman, George Creel, set out to promote what he called “propaganda in the true sense of the word, meaning the ‘propagation of faith.’ ” Wilson also signed the Sedition Act, which criminalized “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government” or anything else that might impede the war effort. The government put up posters around the country urging citizens to report anyone “who spreads pessimistic stories.”

In early 1918, the virus—which would eventually kill more people than all the military deaths of both World Wars combined—infected a large number of men at Camp Funston, an Army base in Kansas, and spread rapidly to other bases. As it slipped into the civilian world, public-health officials “lied for the war effort, for the propaganda machine that Wilson had created,” John M. Barry writes, in his detailed history of the pandemic, “The Great Influenza.” A Navy ship carried the virus to Philadelphia, and sailors started dying, but the city’s public-health director, a political appointee named Wilmer Krusen, dismissed it as “old-fashioned influenza or grip.” As the toll grew, Krusen assured the public that the city was on track to “nip the epidemic in the bud,” and some news organizations became allies in maintaining the façade. A headline in the Inquirer declared, “Scientific Nursing Halting Epidemic,” when, in fact, local hospitals were collapsing under a crush of new cases. The week of that headline, forty-five hundred and ninety-seven people in Philadelphia died of the flu.

In New York and Los Angeles, officials gave similarly false assurances, until the reality became inescapable. Cities and towns were running out of coffins. The clergy started patrolling the streets with carts, Barry writes, calling on the public to bring out their dead. Eventually, it was named the Spanish flu not because it originated in Spain but because when the king, Alfonso XIII, fell ill, the Spanish press was not bound by restrictions against reporting it.

Throughout history, diseases have posed an unsparing test of political leaders and their fidelity to the facts. According to Howard Markel, a medical historian at the University of Michigan, “From the political to the purely mercenary, secrecy has almost always contributed to the further spread of a pandemic and hindered public health management.” In 1892, the German government hid, and thus exacerbated, a cholera epidemic out of fear that sealing the port of Hamburg would be an economic disaster. In 1982, as AIDS was increasingly identified among communities of gay men, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention declared it an epidemic, but, when President Ronald Reagan’s spokesman, Larry Speakes, was asked to comment about it during press briefings, he made jokes. (Reagan finally spoke publicly about the disease in September of 1985.)

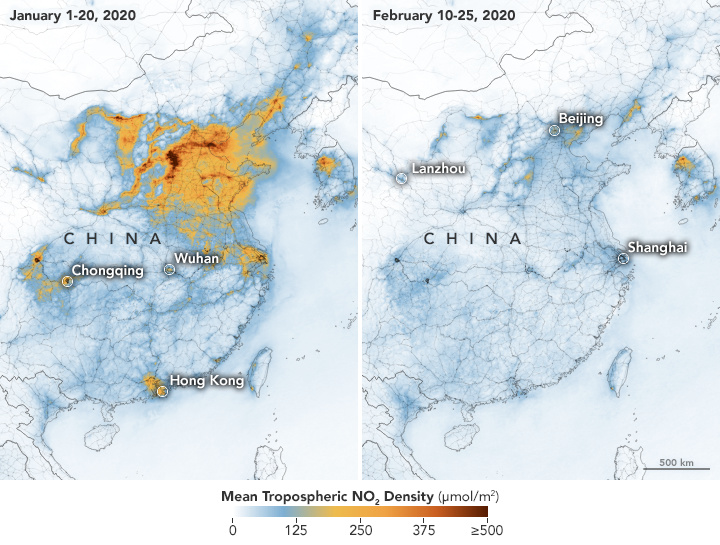

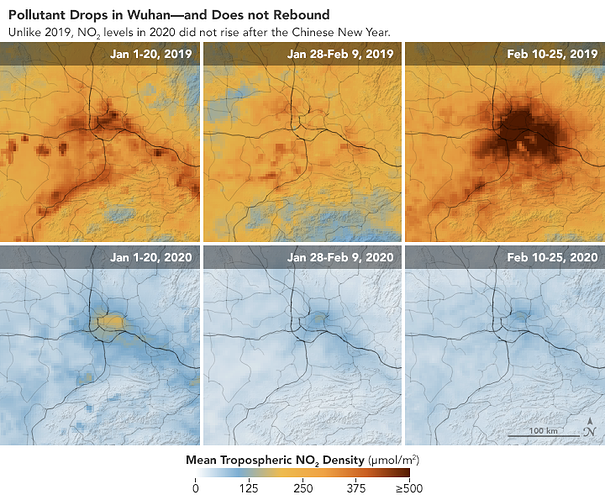

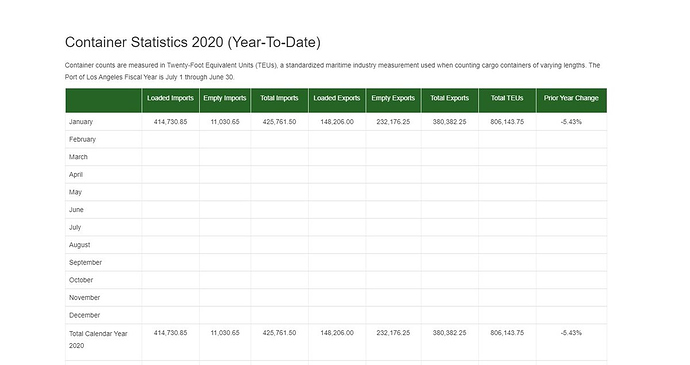

This year, in the first months of the coronavirus epidemic, governments in multiple countries have tried to shape the truth in order to maintain control and deflect criticism. In China, after Li Wenliang, a doctor in Wuhan, drew attention to the new disease, police criticized him for spreading “rumors.” When he died from the virus, the government censored online posts demanding free speech. Even weeks after the virus emerged and started to spread, the local government in Wuhan ordered news organizations to suppress the information and allowed an estimated five million people to leave the city before it was placed under quarantine, on January 22nd.

In Iran, the national government maintained as recently as Tuesday that only twelve people had died of the virus, even though a local health official from Qom had told reporters that, in his city alone, fifty people had died from it. In a moment of cruel farce, on Monday, Iran’s deputy health minister, Iraj Harirchi, appeared on television to downplay the risks, even as he coughed and wiped his brow with a towel. That evening, he learned that he had tested positive for the virus.

When the coronavirus reached the United States in earnest, this month, it became entangled, almost instantly, in political posturing and manipulation. On Monday, Rush Limbaugh, on whom President Trump recently bestowed the Presidential Medal of Freedom, told his audience, “It looks like the coronavirus is being weaponized as yet another element to bring down Donald Trump. Now, I want to tell you the truth about the coronavirus. . . . The coronavirus is the common cold, folks.” On Tuesday, as stock markets collapsed around the world, Larry Kudlow, the White House National Economic Council director, told CNBC, “We have contained this. I won’t say airtight, but it’s pretty close to airtight.” Investors were not reassured; stock markets continued to fall, especially after Kudlow’s optimism was undercut by comments from Nancy Messonnier, the head of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, who warned Americans to prepare for a period of working remotely, teleschooling, and other measures to prevent the spread of the disease.

By midweek, the Administration was straining to rebut warnings from public-health experts. Trump tweeted, “Low Ratings Fake News MSDNC (Comcast) & @CNN are doing everything possible to make the Caronavirus [sic] look as bad as possible, including panicking markets, if possible. Likewise their incompetent Do Nothing Democrat comrades are all talk, no action. USA in great shape!” But the concern was coming not only from Democrats. On Tuesday, when Chad Wolf, the acting Homeland Security Secretary, testified at a Senate budget hearing, he described the death rate from the coronavirus as similar to that of the flu, although, in fact, the coronavirus appears to be more lethal. Senator John Kennedy, a Louisiana Republican, rebuked him. “You’re supposed to keep us safe, and the American people deserve some straight answers on the coronavirus, and I’m not getting them from you,” Kennedy said. Facing bipartisan criticism, the Administration asked Congress for an emergency $2.5 billion to fight the coronavirus.

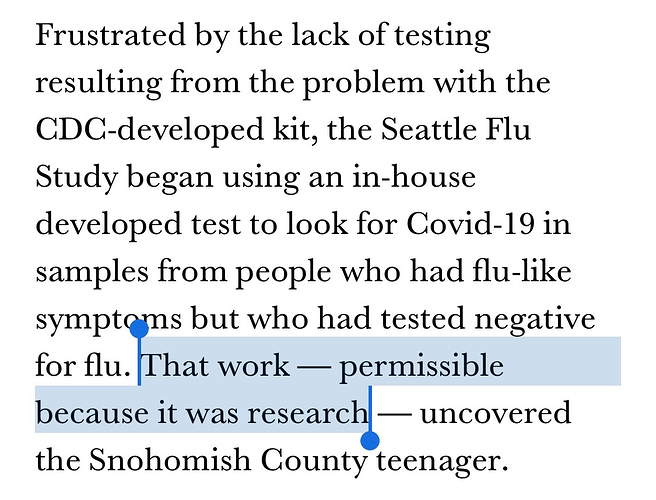

The Administration is also under pressure to fill vacancies that it had created in the government institutions capable of handling such an emergency. During the past two years, it cut the federal ranks of experts involved with infectious-disease emergencies. In February of 2018, the C.D.C. announced plans to stop epidemic-prevention work in thirty-nine out of forty-nine countries that it was monitoring and supporting, leaving ten “priority countries.” China was not one of them. In May, 2018, John Bolton, then the national-security adviser, disbanded the global-health-security team at the National Security Council. Top officials left, and the posts were never refilled.

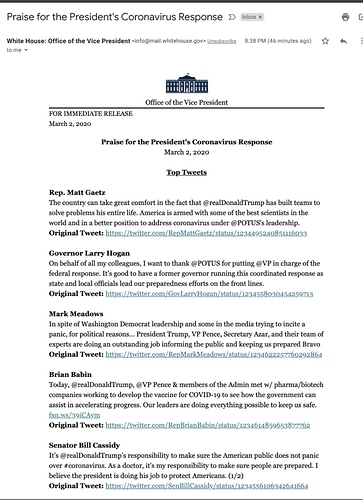

Chuck Schumer, the Senate Minority Leader, called on Trump to appoint a “czar” for the federal response—“an independent, non-partisan, global-health expert, with real expertise.” Instead, on Wednesday, Trump appointed the Vice-President, Mike Pence, to oversee the effort. One of Pence’s first moves, according to the Times , was to “tighten control of coronavirus messaging by government health officials and scientists, directing them to coordinate all statements and public appearances” with his office. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the respected director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who has advised six Presidents, told associates that the White House “had instructed him not to say anything else without clearance,” the Times said. (A spokesperson for the Institute denied that report.)

In 2017, approaching the hundredth anniversary of the Spanish-flu pandemic, John M. Barry wrote that “the most important lesson from 1918 is to tell the truth. Though that idea is incorporated into every preparedness plan I know of, its actual implementation will depend on the character and leadership of the people in charge when a crisis erupts.” By the end of February, as the virus reached farther into the United States, Trump was squaring off against an unfamiliar kind of problem, one that is largely immune to the willful disregard for the facts. A germ is insensitive to the powers of spin. It is a problem that can’t be fudged by scribbling with a Sharpie on a map. How the Administration performs is likely to be a historic test of not only its capacity to function but also of the government’s resilience after three years of Trump’s leadership. Regardless of political orientation, every American should be rooting for the Trump Administration to get this right.