I want this in my President.

It’s Hard to Keep a College Safe From Covid, Even With Mass Testing

The University of Illinois had a state-of-the-art reopening, and then the virus cases piled up.

And this is from my city:

UPDATE: NIU has announced that undergraduate classes will move online for two weeks beginning Monday.

Public health officials say large parties since the return of NIU students have pushed DeKalb County into the warning level for COVID-19 activity.

The Illinois Department of Public Health says DeKalb County is one of 30 in Illinois (shown in orange on map) that are now at warning level, which means there is an increased COVID-19 risk locally.

A county reaches warning level when two or more COVID-19 activity indicators increase. For DeKalb County, that’s new cases and positivity rate.

The DeKalb County Health Department says new cases are now at 122 per 100,000 people when the target is 50. Also, the county’s positivity rate is 8.4 percent when eight or less is the target.

Like other university-host counties, public health officials say the return of students to campus has caused a spike in positives cases.

The DeKalb County Health Department says their case investigations have “determined that a large majority of the cases are specifically linked to large gatherings/parties that have taken place on or around campus.”

It’s expected that NIU today will be announcing new mitigation efforts, and the health department says, “it takes all of our community to decrease the number of cases,” by wearing masks watching social distancing and washing hands.

The health department also announced 11 new positive tests on Friday bringing the county’s total to 1,350. Also, 960 people have now recovered, 37 more than last week.

I am staying away from anybody under 30. And maybe older than 50, given how many idiots I saw out today with their masks on below their noses, mostly 50 and up.

Trump heads into flu season amid pandemic mocking masks, holding packed campaign rallies

He’s choreographed scenes experts warn could lead to illness or even death.

New report exposes how Trump used COVID-19 to enact a dangerous right-wing mission

Crucial Testing for Child Lead Poisoning Has Plummeted During Pandemic

We suspected this all along: Trump’s politically appointed HHS spokesperson & his team demanded & received the right to review & alter CDC’s scientific reports on COVID-19 to health professionals.

Trump officials interfered with CDC reports on Covid-19

The politically appointed HHS spokesperson and his team demanded and received the right to review CDC’s scientific reports to health professionals.

The health department’s politically appointed communications aides have demanded the right to review and seek changes to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s weekly scientific reports charting the progress of the coronavirus pandemic, in what officials characterized as an attempt to intimidate the reports’ authors and water down their communications to health professionals.

In some cases, emails from communications aides to CDC Director Robert Redfield and other senior officials openly complained that the agency’s reports would undermine President Donald Trump’s optimistic messages about the outbreak, according to emails reviewed by POLITICO and three people familiar with the situation.

CDC officials have fought back against the most sweeping changes, but have increasingly agreed to allow the political officials to review the reports and, in a few cases, compromised on the wording, according to three people familiar with the exchanges. The communications aides’ efforts to change the language in the CDC’s reports have been constant across the summer and continued as recently as Friday afternoon.

The CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports are authored by career scientists and serve as the main vehicle for the agency to inform doctors, researchers and the general public about how Covid-19 is spreading and who is at risk. Such reports have historically been published with little fanfare and no political interference, said several longtime health department officials, and have been viewed as a cornerstone of the nation’s public health work for decades.

But since Michael Caputo, a former Trump campaign official with no medical or scientific background, was installed in April as the health department’s new spokesperson, there have been substantial efforts to align the reports with Trump’s statements, including the president’s claims that fears about the outbreak are overstated, or stop the reports altogether.

Caputo and his team have attempted to add caveats to the CDC’s findings, including an effort to retroactively change agency reports that they said wrongly inflated the risks of Covid-19 and should have made clear that Americans sickened by the virus may have been infected because of their own behavior, according to the individuals familiar with the situation and emails reviewed by POLITICO.

Caputo’s team also has tried to halt the release of some CDC reports, including delaying a report that addressed how doctors were prescribing hydroxychloroquine, the malaria drug favored by Trump as a coronavirus treatment despite scant evidence. The report, which was held for about a month after Caputo’s team raised questions about its authors’ political leanings, was finally published last week. It said that “the potential benefits of these drugs do not outweigh their risks.”

In one clash, an aide to Caputo berated CDC scientists for attempting to use the reports to “hurt the President” in an Aug. 8 email sent to CDC Director Robert Redfield and other officials that was widely circulated inside the department and obtained by POLITICO.

“CDC to me appears to be writing hit pieces on the administration,” appointee Paul Alexander wrote, calling on Redfield to modify two already published reports that Alexander claimed wrongly inflated the risks of coronavirus to children and undermined Trump’s push to reopen schools. “CDC tried to report as if once kids get together, there will be spread and this will impact school re-opening . . . Very misleading by CDC and shame on them. Their aim is clear.”

Alexander also called on Redfield to halt all future MMWR reports until the agency modified its years-old publication process so he could personally review the entire report prior to publication, rather than a brief synopsis. Alexander, an assistant professor of health research at Toronto’s McMaster University whom Caputo recruited this spring to be his scientific adviser, added that CDC needed to allow him to make line edits — and demanded an “immediate stop” to the reports in the meantime.

“The reports must be read by someone outside of CDC like myself, and we cannot allow the reporting to go on as it has been, for it is outrageous. Its lunacy,” Alexander told Redfield and other officials. “Nothing to go out unless I read and agree with the findings how they CDC, wrote it and I tweak it to ensure it is fair and balanced and ‘complete.’”

CDC officials have fought the efforts to retroactively change reports but have increasingly allowed Caputo and his team to review them before publication, according to the three individuals with knowledge of the situation. Caputo also helped install CDC’s interim chief of staff last month, two individuals added, ensuring that Caputo himself would have more visibility into an agency that has often been at odds with HHS political officials during the pandemic.

Asked by POLITICO about why he and his team were demanding changes to CDC reports, Caputo praised Alexander as “an Oxford-educated epidemiologist” who specializes “in analyzing the work of other scientists,” although he did not make him available for an interview.

“Dr. Alexander advises me on pandemic policy and he has been encouraged to share his opinions with other scientists. Like all scientists, his advice is heard and taken or rejected by his peers,” Caputo said in a statement.

Caputo also said that HHS was appropriately reviewing the CDC’s reports. “Our intention is to make sure that evidence, science-based data drives policy through this pandemic—not ulterior deep state motives in the bowels of CDC," he said.

Caputo’s team has spent months clashing with scientific experts across the administration. Alexander this week tried to muzzle infectious-disease expert Anthony Fauci from speaking about the risks of the coronavirus to children, and The Washington Post reported in July that Alexander had criticized the CDC’s methods and findings.

But public health experts told POLITICO that they were particularly alarmed that the CDC’s reports could face political interference, praising the MMWRs as essential to fighting the pandemic.

“It’s the go-to place for the public health community to get information that’s scientifically vetted,” said Jennifer Kates, who leads the Kaiser Family Foundation’s global health work. In an interview with POLITICO, Kates rattled off nearly a dozen examples of MMWR reports that she and other researchers have relied on to determine how Covid-19 has spread and who’s at highest risk, including reports on how the virus has been transmitted in nursing homes, at churches and among children.

“They’re so important, and CDC has done so many,” Kates said.

The efforts to modify the CDC reports began in earnest after a May report authored by senior CDC official Anne Schuchat, which reviewed the spread of Covid-19 in the United States and caused significant strife within the health department. HHS officials, including Secretary Alex Azar, believed that Schuchat was implying that the Trump administration moved too slowly to respond to the outbreak, said two individuals familiar with the situation.

The HHS criticism was mystifying to CDC officials, who believed that Schuchat was merely recounting the state of affairs and not rendering judgment on the response, the individuals familiar with the situation said. Schuchat has made few public appearances since authoring the report.

CDC did not respond to a request for comment about Schuchat’s report and the response within the department.

The close scrutiny continued across the summer with numerous flashpoints, the individuals added, with Caputo and other HHS officials particularly bristling about a CDC report that found the coronavirus spread among young attendees at an overnight camp in Georgia. Caputo, Alexander and others claimed that the timing of the August report was a deliberate effort to undermine the president’s push on children returning to schools in the fall.

Most recently, Alexander on Friday asked CDC to change its definition of “pediatric population” for a report on coronavirus-related deaths among young Americans slated for next week, according to an email that Caputo shared with POLITICO.

“[D]esignating persons aged 18-20 as ‘pediatric’ by the CDC is misleading,” Alexander wrote, arguing that the report needed to better distinguish between Americans of different ages. “These are legal adults, albeit young.”

Caputo defended his team’s interventions as necessary to the coronavirus response. “Buried in this good [CDC] work are sometimes stories which seem to purposefully mislead and undermine the President’s Covid response with what some scientists label as poor scholarship — and others call politics disguised in science,” Caputo told POLITICO.

The battles over delaying or modifying the reports have weighed on CDC officials and been a distraction in the middle of the pandemic response, said three individuals familiar with the situation. “Dr. Redfield has pushed back on this,” said one individual. “These are scientifically driven articles. He’s worked to shake some of them loose.”

Kates, the Kaiser Family Foundation’s global health expert, defended the CDC’s process as rigorous and said that there was no reason for politically appointed officials to review the work of scientists. “MMWRs are famously known for being very clear about their limitations as well as being clear for what they’ve found," she said.

Kates also said that the CDC reports have played an essential role in combating epidemics for decades, pointing to an MMWR posted in 1981 — the first published report on what became the HIV epidemic.

“Physicians recognized there was some kind of pattern and disseminated it around the country and the world,” Kates said. “We can now see how important it was to have that publication, in that moment.”

This remark from CNN’s fact checker extraordinaire could fit many categories…

Sigh

Yes, why…beyond imagination and presidential duty.

From nbc…

Stanford medical community denounces Dr. Scott Atlas, the Dr making all the speeches w/ T now and recommending more of a herd immunity approach and getting kids back to schools and

colleges. This community is alarmed at Dr. Atlas lack of experience in the infectious disease area

and their effort to insist that all Dr’s must “do no harm.” (see letter below)

What good this ever does…we will never know. But at least they voiced their very strong opinion.

In the tight-knit world of academic medicine, scientists pride themselves on presenting a united and unflappable face to those outside their ranks.

But this week, in a scathing letter, dozens of Stanford University Medical School’s top faculty denounced former colleague Dr. Scott Atlas for promoting what they called “falsehoods and misrepresentations of science.”

Atlas, a diagnostic radiologist and senior fellow at the conservative think tank Hoover Institution, was recently appointed by President Donald Trump to the White House coronavirus task force.

As an adviser counselor to the president about the virus, he has made controversial statements about controlling the pandemic, which has killed more than 178,000 Americans, through “natural immunity.” He also has urged the reopening of schools and businesses.

“Many of his opinions and statements run counter to established science and, by doing so, undermine public-health authorities and the credible science that guides effective public health policy,” according to the letter, signed by Dr. Philip A. Pizzo, former dean of Stanford School of Medicine; Dr. Upi Singh, chief of Stanford’s Division of Infectious Diseases, and Dr. Bonnie Maldonado, professor of epidemiology and population health, and 105 others.

Among the letter’s signatories are many national experts in the university’s departments of infectious disease, epidemiology and microbiology, including Dr. David Relman, who pioneers methods for discovering new human pathogens, and Dr. Lucy S. Tompkins, who leads Stanford’s Department of Infection Prevention and Control.

“Our goal with this letter was to provide a science-evidence based commentary on some core issues that Scott Atlas has addressed and to provide context and clarity,’said Pizzo, who now leads The Stanford Distinguished Careers Institute.

“We are motivated by our responsibility to do all we can to protect and promote public health and wellbeing,” he said.

Letter

The Other Way Covid Will Kill: Hunger

Worldwide, the population facing life-threatening levels of food insecurity is expected to double, to more than a quarter of a billion people.

Long before the pandemic swept into her village in the rugged southeast of Afghanistan, Halima Bibi knew the gnawing fear of hunger. It was an omnipresent force, an unrelenting source of anxiety as she struggled to nourish her four children.

Her husband earned about $5 a day, hauling produce by wheelbarrow from a local market to surrounding homes. Most days, he brought home a loaf of bread, potatoes and beans for an evening meal.

But when the coronavirus arrived in March, taking the lives of her neighbors and shutting down the market, her husband’s earnings plunged to about $1 a day. Most evenings, he brought home only bread. Some nights, he returned with nothing.

“We hear our children screaming in hunger, but there is nothing that we can do,” said Ms. Bibi, speaking in Pashto by telephone from a hospital in the capital city of Kabul, where her 6-year-old daughter was being treated for severe malnutrition. “That is not just our situation, but the reality for most of the families where we live.”

It is increasingly the reality for hundreds of millions of people around the planet. As the global economy absorbs the most punishing reversal of fortunes since the Great Depression, hunger is on the rise. Those confronting potentially life-threatening levels of so-called food insecurity in the developing world are expected to nearly double this year to 265 million, according to the United Nations World Food Program.

Worldwide, the number of children younger than 5 caught in a state of so-called wasting — their weight so far below normal that they face an elevated risk of death, along with long-term health and developmental problems — is likely to grow by nearly seven million this year, or 14 percent, according to a recent paper published in The Lancet, a medical journal.

The largest numbers of vulnerable communities are concentrated in South Asia and Africa, especially in countries that are already confronting trouble, from military conflict and extreme poverty to climate-related afflictions like drought, flooding and soil erosion.

At least for now, the unfolding tragedy falls short of a famine, which is typically set off by a combination of war and environmental disaster. Food remains widely available in most of the world, though prices have climbed in many countries, as fear of the virus disrupts transportation links, and as currencies fall in value, increasing the costs of imported items.

Rather, with the world economy expected to contract nearly 5 percent this year, households are cutting back sharply on spending. Among those who went into the pandemic in extreme poverty, hundreds of millions of people are suffering an intensifying crisis over how to secure their basic dietary needs.

The pandemic has reinforced basic economic inequalities, none more defining than access to food.

‘Shock upon shock upon shock’

In South Africa, more than a quarter-century has passed since the official ending of apartheid, yet the Black majority remains overwhelmingly confined to poor townships that are far removed from jobs and services in the cities. When the pandemic emerged in March, the government ordered the shutdown of informal food vendors and township shops, unleashing the military to detain merchants who violated orders. That forced residents to rely on supermarkets — suddenly farther away than ever, given the lockdown of already woeful bus service.

At the same time, South Africa closed its schools, eliminating school lunches — the only reliable meal for millions of students — just as breadwinners lost their means of getting to jobs. By the end of April, nearly half of all South African households had exhausted their funds to buy food, according to an academic study. Social unrest eventually prompted a loosening of the country’s restrictions.

Far from a danger confined to the world’s poorest countries, hunger is a growing scourge even in the wealthiest countries. Previously working people who have never felt compelled to seek help are now lining up at food banks in the United States, Spain and Britain. Even people of relative means are cutting their purchases of fresh fruits and vegetables, while relying more on the cheap calories of fast food.

In wealthier countries, the economic strains are cushioned by government programs like unemployment benefits, subsidized wage plans and cash grants for food. In the poorest countries, the coronavirus is intensifying a litany of already potent afflictions.

“Covid has been yet another shock in what has been a terrible year in this region,” said Michael Dunford, regional director for East Africa at the World Food Program. “In addition to already having 21 million people acutely food insecure at the beginning of the year, we’ve then had flooding, locusts, and now we’ve got Covid. So it’s shock upon shock upon shock, which is just increasing vulnerability throughout the region.”

Just as the need for help intensifies, the threat of the virus is forcing relief agencies to scrap public health campaigns and limit their outreach. Lockdowns imposed to halt the pandemic will this year deprive 250 million children in poor countries of scheduled supplements of Vitamin A, elevating the threat of premature death, according to UNICEF. The supplements strengthen the immune system, limiting vulnerability to diseases that opportunistically exploit malnutrition.

The virus has also forced the delay of other immunization programs, which are typically combined with doses of deworming medicine — another bulwark against malnutrition.

“I’m increasingly concerned about the socioeconomic impacts of the pandemic on the nutrition situation of children,” said Victor Aguayo, chief of nutrition programs at UNICEF in New York. “It’s a perfect storm to see an increase in malnutrition rates if appropriate measures and programs are not put in place.”

Only the latest plague

In Juba, the capital of South Sudan, the pandemic was merely the most recent form of grave danger.

A sense of crisis has prevailed since a paroxysm of violence four years ago in a long-running civil war fueled by ethnic division. Amid the fighting, people fled the surrounding countryside for refuge in camps inside the city. Without access to their fields, many became dependent on food distributed by relief agencies along with anything they could buy at the market.

South Sudan was already one of the world’s poorest countries, with 80 percent of its roughly 11 million people living in a state of absolute poverty, surviving on less than $2 a day, according to the World Bank. The reinvigorated conflict posed an economic shock. As the government printed currency to pay its bills, runaway inflation resulted, dropping teachers’ salaries from the equivalent of $100 a month to $1.

Food prices soared. Most items were trucked in from neighboring Kenya and Uganda and priced in dollars, making them more expensive as the nation’s currency plunged. A 50 kilogram (110 pound) bag of corn flour that fetched $20 four years ago was more than $30 by late last year.

Poverty and hunger proved mutually reinforcing. As mosquito nets increased in price, that enhanced the risks of a lethal strain of malaria, which itself reduced appetites and worsened malnutrition among children.

Last year, heavy rains that fell in too short a time created torrential flooding that decimated crops and killed cattle.

By the beginning of 2020, roughly six million people in South Sudan were technically food insecure, meaning they could not reliably count on satisfying their dietary requirements.

“Nutrition is a lot more than food,” said Mads Oyen, chief of field operations for UNICEF in South Sudan, speaking by videoconference from Juba. “You’ve got malaria and measles and a lack of nutrients and other health issues. It’s about lack of clean water, which means cholera.”

This was all before the arrival of the worst pandemic in a century.

As the virus sowed chaos in transportation networks across East Africa, the price of staple foods sold in Juba leapt another 25 percent. At the same time, a lockdown imposed by the government derailed local businesses like food stalls, decimating incomes.

These were the forces that brought Mary Pica to a primary health care center in Juba in early May. It was run by the international relief organization World Vision. She carried her then-10-month-old son. He weighed only 5.4 kilograms (11.9 pounds), well below healthy.

Ms. Pica lived with her husband’s family in a household of nine people. Her husband had worked loading baggage onto buses. That job was a casualty of the fighting, as bus service largely shut down.

Her mother-in-law grew greens on a small plot of land outside Juba, using the proceeds to buy other items that balanced their diet — yogurt, fruit, fish and eggs. With the market closed, she could not earn cash. The family was subsisting almost entirely on greens. Ms. Pica, who had become pregnant again, was no longer breastfeeding her baby. He was wasting away.

The clinic provided her with a peanut-based paste donated by UNICEF. Every two weeks, she goes back to pick up another supply. The baby has been gaining weight.

But Ms. Pica sees dangers everywhere. Her sister-in-law’s child, a 2-year-old boy, has malaria. The pandemic is unrelenting.

“I’m worried,” she said, speaking in Arabic by phone from Juba. “I have no hope that the situation will change tomorrow. I can only pray to God that it changes.”

‘Money is the law’

Food prices have been rising in much of Africa for the same reason that Samuel Omondi has endured nearly six months without seeing his wife and five children in western Kenya — because of the chaos gripping the roads.

A father of five, Mr. Omondi, 42, makes his living driving a truck, typically hauling wheat. It used to take him four days to complete his usual round-trip from the Kenyan port of Mombasa to the Ugandan capital of Kampala, a distance of 1,400 miles. Now, the same journey requires eight to 10 days.

Drivers cannot enter either country without certificates showing they are free of Covid. Uganda has required that every driver submit to a test at the border, waiting as long as four days for results.

Throughout the region, immigration and customs checks have become so onerous that lines form 40 miles before borders. Trucks progress slowly, in low gear, consuming extra fuel. Drivers submit to the maddening wait while fretting over increased costs.

“You know you are going to spend three days in the truck without taking a bath,” Mr. Omondi said. “You can’t even park on the side of the road and relax. People will pass you.”

Along their journeys, drivers get hostility from communities that view them as disease carriers. They bring their own groceries, fearful of stopping in major towns and drawing attention.

“People are saying we are bringing Covid,” Mr. Omondi said. “There was a child in Uganda who looked at us truck drivers and said, ‘Mama, do you see these people with corona?’”

Yet he cannot go home, knowing that the chief in his area will force him into quarantine. “We are suffering a lot,” he said.

Given the delays and the bothers, he and other truck drivers have been making fewer trips a month, diminishing their income and diminishing the supply of food in many cities.

As convoys roll slowly toward border crossings in the heat, containers full of fish, chicken, bananas and other perishable goods are rotting.

The movement of food has also been hampered by corruption. In many countries, police stop truck drivers to inspect their Covid certificates, engendering a flourishing trade in fake documents. Border officials exploit the pandemic as a fresh opportunity to extract bribes.

“There’s no law at the borders,” said Joel Ombaso, a wholesale fruit dealer in Nairobi. “Money is the law.”

He buys oranges from Tanzania and pineapples and bananas from Uganda. He must usually dispense hundreds of dollars in bribes to get his cargo into Kenya, he said. There, he sells the fruit to local grocery stores. A curfew in Nairobi has prevented delivery at night, imposing further delays that have damaged shipments. Since the pandemic began, Mr. Ombaso’s profits have plunged by nearly three-fourths, he said.

An outbreak of pandemic-related nationalism — with countries blaming one another for the spread of the disease — has produced an escalating wave of trade barriers that has amplified the trouble on the roads. Rwanda has refused to allow Tanzanian truck drivers to haul goods into the country, forcing a time-consuming change of driver at the border.

All of these factors have combined to limit the supply of food, pushing prices higher, just as vast numbers of people have seen their incomes depleted.

In a recent survey conducted by the International Committee of the Red Cross in 11 African countries — among them Kenya, Ethiopia, Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo — 85 percent of the respondents said food was available in their local markets. But 94 percent reported that prices had increased, and 82 percent said incomes were down.

Ethiopians are voracious consumers of onions, folding them into seemingly every dish. Much of this staple is imported from neighboring Sudan. But with the border now shut, the price of onions has skyrocketed in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, home to six million.

This has tightened the pressure on Mulunesh Moges, 38, a mother of two who sells clothes at an open air market.

“My customers are almost down to zero,” Ms. Moges said. “I sit at my shop the whole day without doing anything.” Her daily earnings used to run about 200 Ethiopian birr (about $5) — enough to feed her family. Lately, she has earned next to nothing.

“We used to eat three times a day,” she said. “Now it’s once or twice. I’m always calculating what to feed my children.”

Birchat Abdala runs a street-side tea and coffee kiosk. Her daily earnings have dropped by more than two-thirds to 30 birr (about 83 cents).

“In the morning, I used to feed my children eggs and bread,” she said. “Now, I feed them only bread, or whatever is left over from my business. We eat whatever we can get our hands on.”

A counterintuitive problem: Falling demand

Across the Arabian Sea, in the Indian capital of New Delhi, Champa Devi and her family have responded to a loss of income by downgrading their diet.

She earns her living cleaning homes. Her husband lost his job as a driver early in the year. Then the pandemic emerged, prompting Prime Minister Narendra Modi to impose a lockdown, and making it virtually impossible for her husband to find another job. Their favorite fruits, bananas and apples, have become luxuries they can no longer afford.

“We have to squeeze our wallets," said Ms. Devi, 29, the mother of a 9-month-old daughter. “Now, we’re surviving on dal and roti ” — the Indian staple of watery lentils and flatbread.

The shutdown eliminated paychecks for office workers in major cities. Migrant workers lost their construction jobs. The poorest of the poor were deprived of meager livings gained by gathering scraps of metal and plastic from streets. This translated into a monumental reduction of spending power in a nation of 1.3 billion.

And that produced what seems like a counterintuitive problem in the midst of rising hunger: Falling demand for crops.

In the northern Indian state of Haryana, Satbir Singh Jatain last month relinquished his bottle gourds to the elements, allowing them to rot on the vine rather than wasting the effort to harvest them. The price they would have fetched would not have covered the cost of labor or transportation.

“There’s no point in even picking them and taking them to the market,” he said.

Since the lockdown, Mr. Jatain, a third-generation farmer, has lost over 700,000 rupees ($10,000), he said.

Initially, he could not get his tomatoes to market. What little he gained by selling the crop near his village covered less than a third of his costs. As the tomatoes began rotting, he became so enraged that he ran them over with a tractor.

“The lockdowns have destroyed farmers,” he said. “Now, we have no money to buy seeds or pay for fuel.”

Across India, farm laborers complain they are not being paid, forcing their families to cut their spending on food.

Mr. Jatain is on the hook for bank loans reaching nearly $18,000. He owes money lenders in his village. “I can never pay it back, and soon they will come for my land,” he said. “There is nothing left for us.”

The perils of seeking help

In Afghanistan, Ms. Bibi felt a mixture of dread and terror as her 6-year-old daughter, Zinab, sank further into a state of malnutrition. Her skin was going pale as her body diminished. She was losing energy.

“I could see with my own eyes that the child was withering away,” Ms. Bibi said.

She had taken her daughter to several supposed doctors around her village. They administered folk remedies, advised prayer and urged Zinab to eat. But her appetite was minimal. And the family had little food.

The prices of staples like flour, rice, cooking oil and sugar were all rising. Many of these products were trucked in from Pakistan, Iran and Kazakhstan. So long as the market remained closed, Ms. Bibi’s husband was without work.

By the middle of July, Zinab required serious medical attention, necessitating a trip to the capital city of Khost Province. Ms. Bibi was deeply reluctant to make the journey. Getting to the city entailed a 90-minute drive through a forbidding landscape rife with tribal conflicts, the territory controlled neither by the Afghan government nor the insurgent Taliban. The roads were too frequently lined with deadly explosive devices.

And now a new horror was layered atop the usual sources of fear. The coronavirus had killed more than 15 people in her village of perhaps 500. Beyond its confines lay a seemingly infinite number of potential carriers.

This was the calculation that was preventing people from seeking critical care throughout Afghanistan. Between January and May, the number of Afghan children under 5 who were suffering from severe acute malnutrition — a condition requiring hospitalization — increased to 780,000 from 690,000, according to Zakia Maroof, a nutrition expert with UNICEF in Kabul. Since March, the number of children admitted to hospitals has declined 40 percent.

But if Ms. Bibi was frightened to venture out, she was even more disturbed by the alternative.

“It was either be afraid of the coronavirus and watch my child die,” she said, “or at least tell my heart that I did what I had to do.”

Her husband borrowed from relatives to cover their medical bills, and they climbed aboard a minibus.

At a rudimentary hospital in the city of Khost, doctors administered a diet of powdered milk. After three weeks there, with bills mounting, Zinab was still losing weight. The doctors pronounced their capabilities exhausted. The family would have to go to Kabul, another seven-hour ride away.

Her husband went out to the streets and begged, amassing the funds for a ride in a beat-up station wagon headed for Afghanistan’s capital.

They rode through the blazing August heat, arriving in a bustling city they had never visited, and where they knew no one. They beseeched strangers to direct them to a children’s hospital. A kindly soul led them to the Indira Gandhi hospital, which was run by the Indian government and supported by UNICEF.

Zinab was admitted and administered regular feeding by a tube inserted through her nose. She weighed only 8.5 kilograms (less than 19 pounds). Two weeks later, she was still shedding weight, her system struggling to hold food down.

Ms. Bibi sat by her side, keeping vigil, fretting about the bills and wondering how they might find their way home.

Getting to a signed Covid relief bill is the goal and Pelosi 'n co do not want the slimmed down version of the existing one on the table. She’s demanding that the House stay in session until they’ve reached a deal. The demands the Dems have include adding to the additional funds to unemployed workers, getting a $1200 check to those making less than $100K per year, and money for schools.

Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) is standing firm on Democrats’ demands for broad COVID-19 relief, shrugging off mounting pressure from Senate Republicans and a small but vocal group of moderate lawmakers in her caucus to pass a slimmer bill.

Her strategy carries risks, just weeks before Election Day, if voters deem House Democrats to be the main obstacle to another round of coronavirus aid, particularly after Senate Republicans mustered 52 votes in favor of their pared-down measure last week.

With that in mind, a growing number of moderate Democrats — including leaders of the Blue Dogs and the New Democrat Coalition, as well as a number of front-line lawmakers facing tough reelections — have pressed Pelosi and Democratic leadership to stage a pre-election vote on some version of emergency assistance for states, households and small businesses struggling through the pandemic, even if the package doesn’t check every box on Pelosi’s wish list.

“They do feel strongly about the fact that leadership does need to negotiate with each other on a deal,” said a senior Democratic aide associated with the moderate wing of the party. “A vote on something before the members go back home,” the aide added, would “indicate at least that Democrats are moving toward a negotiating stance.”

Yeah on one hand I see the need for help now for those who need it most, but on the other, for all the questionable statements and decisions she’s made, she is 100000% percent right about what doing this piecemeal would mean and that it’s a bad idea to do yet another “emergency relief bill.” On the appropriate third hand, fuck Blue Dogs.

Anti-maskers forced to dig graves for COVID-19 victims in Indonesia

1

Coronavirus death toll from Maine wedding rises to 7, with over 175 infected

Outbreaks at a rehabilitation center and a county jail have been linked to the wedding and reception in August.

The death toll from a coronavirus outbreak linked to an indoor wedding and reception in Maine has risen to seven, with the number of cases connected to the event up to 176.

The latest death was reported at the Maplecrest Rehabilitation Center in Madison, where five prior deaths were also deemed connected to the Aug. 7 wedding and reception. One person died at a hospital in the Millinocket area, a spokesman for the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention said Tuesday.

About 65 people attended the event, in violation of Gov. Janet Mills’ executive order limiting indoor gatherings to 50 people, the Maine CDC has said.

The wedding ceremony was held at Tri Town Baptist Church in East Millinocket, about 63 miles north of Bangor, and a reception was held at the Big Moose Inn Cabins and Campground in Millinocket.

A person who answered the phone Tuesday at Big Moose Inn said they are not commenting and the church could not immediately be reached.

None of the seven people who have died attended the wedding or the reception.

But among those who did attend the event was an employee of the York County Jail, where 72 cases have been linked to the gathering, health officials have said.

Maine health officials have also said the wedding and reception are tied to the virus’ spread at a Madison rehabilitation center.

And, the state is investigating whether an outbreak at Calvary Baptist Church, whose pastor officiated at the wedding, is linked to the event. The church is tied to at least 10 cases.

In a statement Tuesday, the church said a number of its members attended the wedding reception and it defended its right to continue holding services.

“The Calvary Baptist Church has a legal right to meet. The authority of a local Christian church, a Jewish synagogue, or a Muslim mosque to gather for their respective religious services is a time-honored part of our nation’s history since its inception,” the statement said, according to The Associated Press. “These religious activities are also fully protected under the First Amendment to our United States Constitution.

The number of cases stemming from the wedding and reception has steadily grown.

In August, health officials said they had identified 18 people who tested positive for the coronavirus after attending the event. Another six people who had close contact with those attendees also tested positive, according to a state press release on Aug. 17.

By the first week of September, nearly 150 cases and three deaths were linked to the event.

State health officials did not immediately release details on the seventh death. Maplecrest Rehabilitation Center did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Maine wedding ‘superspreader’ event is now linked to seven deaths. None of those people attended.

2

Trump is now officially pushing herd immunity… kind of.

Coronavirus live news: Trump says Covid-19 will ‘go away’ because of ‘herd mentality’

Trump defends claim coronavirus will disappear, citing ‘herd mentality’

President Trump defended his assertion that the novel coronavirus would “disappear” with or without a vaccine on Tuesday, saying the United States would develop what he called “herd mentality.”

“With time it goes away,” Trump said during an ABC News town hall in Pennsylvania when pressed by host George Stephanopoulos on his public comments about the virus. “You’ll develop, you’ll develop herd — like a herd mentality. It’s going to be, it’s going to be herd-developed, and that’s going to happen. That will all happen. But with a vaccine, I think it will go away very quickly.”

Trump appeared to mistake “herd mentality” for “herd immunity,” which occurs when enough individuals develop immunity to prevent the spread of a disease.

Trump went on to insist that the United States is “rounding the corner” with respect to the coronavirus, which has killed nearly 200,000 people in the U.S. Top health officials, meanwhile, have warned of the possibility of a dangerous public health situation in the fall if a second wave of COVID-19 coincides with flu season.

Last week, Anthony Fauci, a key member of the White House coronavirus task force, said he disagreed with Trump’s claim that the U.S. was rounding the “final turn” on the virus.

“A lot of people do agree with me,” Trump told Stephanopoulos when pressed on Fauci’s disagreement. “You look at Scott Atlas. You look at some of the other doctors that are highly — from Stanford. Look at some of the other doctors. They think maybe we could have done that from the beginning.”

Atlas, a senior fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, was added as one of Trump’s coronavirus advisers in August. The Washington Post reported last month that Atlas was pushing the White House to adopt a “herd immunity” strategy, though the White House has denied that the administration has ever considered such a policy to address the coronavirus pandemic.

The president offered a consistent defense of his response to the coronavirus on Tuesday, despite criticism of his rhetoric on the virus and his administration’s handling of the pandemic. Polls show a majority of Americans disapprove of Trump’s handling of the virus.

Trump denied downplaying the virus publicly, despite a recording of March interview with journalist Bob Woodward during which he acknowledged “playing it down” in order to avoid “panic.” Trump said he was not looking to be dishonest with the public and said he regretted nothing about his response, saying his administration had done a “great job.”

The president also repeatedly touted his administration’s work toward securing a vaccine, saying at one point a vaccine could be ready within “three weeks, four weeks” — a statement that is sure to encounter skepticism within the health community. Fauci has said a vaccine could be available by the end of the year.

Trump’s ABC News town hall: Full transcript

The president answered voters’ questions Tuesday in Philadelphia.

Trump Says With ‘A Herd Mentality’ Covid-19 Coronavirus Will Go Away

3

Emails Show the Meatpacking Industry Drafted an Executive Order to Keep Plants Open

Hundreds of emails offer a rare look at the meat industry’s influence and access to the highest levels of government. The draft was submitted a week before Trump’s executive order, which bore striking similarities.

More than 200 meat plant workers in the U.S. have died of covid-19. Federal regulators just issued two modest fines.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/osha-covid-meat-plant-fines/2020/09/13/1dca3e14-f395-11ea-bc45-e5d48ab44b9f_story.html

Federal regulators knew about serious safety problems in dozens of the nation’s meat plants that became deadly coronavirus hot spots this spring but took six months to take action, recently citing two plants and finally requiring changes to protect workers.

The financial penalties for a Smithfield Foods plant in South Dakota and a JBS plant in Colorado issued last week total about $29,000 — an amount critics said was so small that it would fail to serve as an incentive for the nation’s meatpackers to take social distancing and other measures to protect their employees.

Meat plant workers, union leaders and worker safety groups are also outraged that the two plants, with some of the most severe outbreaks in the nation, were only cited for a total of three safety violations and that hundreds of other meat plants have faced no fines. The companies criticized federal regulators for taking so long to give them guidance on how to keep workers safe.

At least 42,534 meatpacking workers have tested positive for the novel coronavirus in 494 meat plants, and at least 203 meatpacking workers have died since March, according to an analysis by the Food Environmental Reporting Network, a nonprofit investigative news organization.

At the Smithfield plant in Sioux Falls, S.D., 1,294 have tested positive for the coronavirus and four have died. At the JBS USA plant in Greeley, Colo., 290 have tested positive and six have died.

Smithfield last year had revenue of nearly $14 billion. JBS — the largest meatpacker in the world — had $51.7 billion in revenue. Both companies, which operate internationally, said that the citations are “without merit,” that they will contest them and that they have already made safety improvements.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration said the plants failed to provide a workplace “free from recognized hazards that were causing or likely to cause death or serious physical harm to employees in that employees were working in close proximity to each other and were exposed to” the coronavirus.

The citations also said the companies “did not develop or implement timely and effective measures to mitigate exposures.”

In addition to improving distancing between employees, OSHA ordered the companies to erect barriers between the workers when that isn’t possible. With Smithfield, OSHA said the plant needed to adjust processing line speeds “to enable employees to stand farther apart.”

The companies, worker safety groups and meat plant workers criticized OSHA for how long it took the agency to complete investigations of the plants.

“Where were they when people were getting sick and were hospitalized? When people were dying?” said Debbie Berkowitz, a worker-safety expert with the nonprofit National Employment Law Project. “Just think about how many lives could have been saved and how many people may not have gotten sick.”

Mark Lauritsen, vice president and director of food processing, packing and manufacturing with the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union (UFCW), said he believes the sudden issuance of citations, months after the plants were spiking with coronavirus cases, is motivated by the upcoming election.

“They checked out and turned a blind eye to this for months. The Trump administration made these decisions to not step in and help workers,” Lauritsen said. “Now they are trying to look like they are doing their job so they can cover themselves politically. People in this country remember the horror of what happened to these workers.”

The White House did not respond to a request for comment.

Of the nearly 10,000 virus-related requests OSHA received to investigate workplaces in all industries since early March, Smithfield and JBS are the only ones that have so far resulted in a citation and fine. Unrelated to the complaints, OSHA has issued six other virus-related citations and fines for industries other than the meat industry, which resulted from routine reports the agency received from hospitals and employers about workers being hospitalized or fatally injured, records show.

The massive coronavirus outbreaks at meat plants — and the lack of masks and social distancing that fueled the virus’s spread — has been widely reported by media since March and April.

Keira Lombardo, executive vice president of corporate affairs and compliance at Smithfield, criticized OSHA, saying the agency was slow to issue guidance to meatpackers, adding, “Despite this fact, we figured it out on our own.”

She also said the company “simultaneously and repeatedly urged OSHA to commit the time and resources to visit our operations in March and April. They did not do so.”

JBS also was critical of OSHA’s response to the pandemic, saying the agency did not provide guidance until late April on ways to remedy safety problems that would have prevented the spread of the coronavirus in plants.

“The OSHA citation . . . attempts to impose a standard that did not exist in March as we fought the pandemic with no guidance,” JBS said in a statement. “Every proposed abatement in the citation was implemented months ago in Greeley. These abatements would have been informative in February. Today, they don’t even meet our internal standards.”

The North American Meat Institute, a trade association, also criticized the “inconsistent and sometimes tardy government advice” in a statement and said the industry quickly took steps to protect workers when the virus hit in March. It also said confirmed coronavirus cases among plant workers have dropped significantly in recent months because of measures taken in the plants.

In response to the criticism, OSHA said that its investigative process is “exhaustive” and that it met legal mandates because it has “a six month statute of limitations to complete any investigation and issue a citation.” In response to Smithfield’s statement, OSHA also said, “The risks and precautions needed were well-known at the time and Smithfield did not address them in a timely manner.”

Kim Cordova, president of the UFCW Local 7, which represents the JBS employees, said she worries the small fines may actually make conditions worse for plant workers.

“These tiny fines are nothing to [meat plant owners]. They give an incentive to make these workers work faster and harder in the most unsafe working conditions imaginable,” said Cordova, referencing JBS’s $15,615 fine.

Sandra Sibert, a union representative at the Smithfield plant who debones hams on the early-morning shift, said she sent emails in mid-March to the White House and Smithfield’s human resources department telling them about the grave concerns she had: Thousands of employees were working without masks, workers were packed like “tuna in a can” on processing lines, and several areas within the plant had no hand sanitizer.

“They did not sit down with me,” said Sibert, who tested positive for the coronavirus in early April and took several weeks to recover. “They only emailed or [left a] message saying they appreciated my concerns.”

When OSHA inspectors arrived at the plant April 20, she was hopeful, but she, too, is disappointed with the outcome. Like Cordova, she worries the OSHA fine is not enough to prompt the company to create more social distancing in the plant, which, records show, Smithfield has fought.

The $13,494 fine, Sibert said, was too low. “It isn’t going to scare them,” she said. “They make that kind of money in a half-hour — less.”

By contrast, California, which runs its own OSHA program, fined a meat plant about $220,000 last week for similar violations.

OSHA defended itself by saying it issued the maximum fine allowed under the law — $13,494 — for citations for a serious violation. Each company received that, and JBS also received a $2,121 fine for an “other-than-serious” violation.

However, critics said their problem was not with the dollar amount for a single violation; their frustration is with the agency’s citation of only one serious violation for each plant. OSHA declined further comment on the fine amounts.

Both companies have fought strict enforcement measures on social distancing and state-ordered quarantines they say drove up absentee rates among workers.

In mid-March, Smithfield Foods’s chief executive, Kenneth Sullivan, sent a letter to Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts ® saying he had “grave concerns” that the state’s stay-at-home orders were causing “hysteria.”

“We are increasingly at a very high risk that food production employees and others in critical supply chain roles stop showing up for work,” Sullivan wrote in a letter obtained by the nonprofit journalism outlet ProPublica. “This is a direct result of the government continually reiterating the importance of social distancing, with minimal detail surrounding this guidance.”

He added: “Social distancing is a nicety that makes sense only for people with laptops.”

In a June 30 letter to Democratic Sens. Elizabeth Warren (Mass.) and Cory Booker (N.J.), Sullivan again pushed back on concerns the lawmakers raised regarding the company’s handling of the virus in their plants.

“Please understand, processing plants were no more designed to operate in a pandemic than hospitals were designed to produce pork,” Sullivan wrote. “In other words, for better or worse, our plants are what they are. Four walls, engineered design, efficient use of space, etc. Spread out? Okay. Where?”

JBS flexed its muscle to reopen its doors before it had implemented many of the safety measures Weld County health officials mandated for the Greeley plant in April, when they ordered the plant to close because of coronavirus outbreaks, records show.

Company executives successfully enlisted Vice President Pence and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Robert Redfield to help keep the plant running. On April 10, when the closure order was sent for the plant, Pence and President Trump both mentioned the Greeley plant at the day’s White House coronavirus briefing, promising testing resources to the plant.

An hour later, JBS USA chief executive Andre Nogueira publicly thanked Pence in a news release. Pence spokesman Devin M. O’Malley said other meat plants also were helped and that the vice president’s “efforts were instrumental in ensuring that Americans did not experience food shortages during the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak.”

The day after the county’s closure order, Jill Hunsaker Ryan, director of Colorado’s health agency, wrote in an email to then-Weld County health director Mark Wallace, saying she had received a call from Redfield regarding the Greeley plant.

“JBS was in touch with the VP who had Director Redfield call me,” she wrote in the April 11 email. Redfield wanted the local and state health authorities to send “asymptomatic people back to work even if we suspect exposure but they have no symptoms,” Ryan wrote. She said she was okay with that if Wallace was.

A state health department employee, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of fears of retribution from the federal government, said they complied with Redfield’s request out of fear that the state would be cut off from aid it needed from CDC to manage the pandemic.

The employee confirmed there was “heavy involvement from high levels within the federal government.”

Basically, these companies killed 200 people and got fined the barest fraction of what they make for it, telling them they can do this with impunity.

CDC Director Dr. Redfield and others testify on Coronavirus Response

https://www.c-span.org/video/?475764-1/cdc-director-dr-redfield-testify-coronavirus-response

Adding

Mask might offer more protection against Covid than vaccine per Dr. Redfield.

video

WOW Per Dr. Redfield - vaccine available 2nd qtr/3rd qtr 2021

“Herd mentality” ffs

A vaccine is much further out on the calendar than we had anticipated. Hearing a bit of this today from the CDC interviews today.

It will likely be at least six to eight months longer before a coronavirus vaccine can be distributed in a best-case scenario, leading Maryland health officials and lawmakers said as they make plans for the state.

Senate President Bill Ferguson said he spoke on Tuesday with one of the principal investigators at Johns Hopkins University who is working on a vaccine now in its third phase. While there has been remarkable progress, Ferguson said Wednesday that the logistics that go into distributing a vaccine are “enormous and herculean.”

“I think it’s really important that we keep that in mind moving forward as we make decisions about the future of Maryland — that even with an amazing light-speed approval, it is still six to eight months from that point until we’ll start to see the impact on herd immunity overall, so there is time to go in this ballgame,” Ferguson, a Baltimore Democrat, said during a meeting of a legislative panel on the coronavirus.

Robert Neall, Maryland’s health secretary, emphasized that people need to be prepared to use available tools like masks and handwashing well into next year.

And this part was clarified - masks are better than the vaccine right now.

(CNN)President Donald Trump’s own health officials continue to publicly contradict him when it comes to the coronavirus pandemic – this time on the importance of mask wearing.

In fact, Dr. Robert Redfield, the director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, testified that mask wearing may be a more effective protection against coronavirus than the potential vaccine that the President can’t stop hyping.

"I might even go so far as to say that this face mask is more guaranteed to protect me against Covid than when I take a Covid vaccine, because the immunogenicity may be 70%. And if I don’t get an immune response, the vaccine is not going to protect me. This face mask will," Redfield told lawmakers during public testimony on Wednesday, adding that the American public has not yet embraced the use of masks to a level that could effectively control the outbreak.

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure

It is meaningful because it is him saying that it won’t be ready.

Althooooooooooooough he also said “well the vaccine may not work anyway” so shit we’re back to square one.

Even when he’s doing things right he’s screwing them up somehow.

No fucks left Michael Steele is the best Michael Steele.

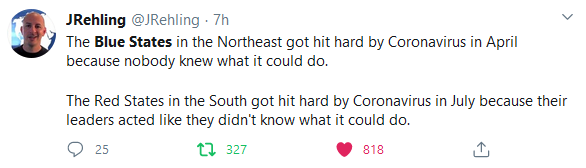

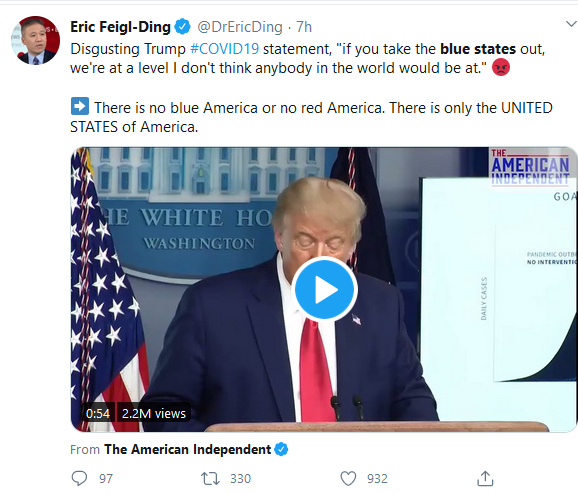

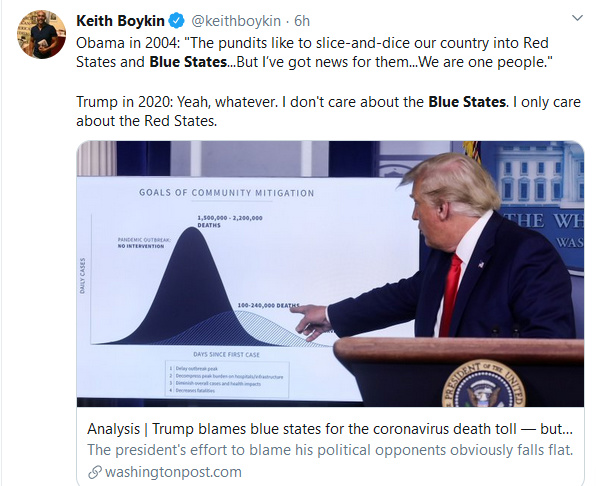

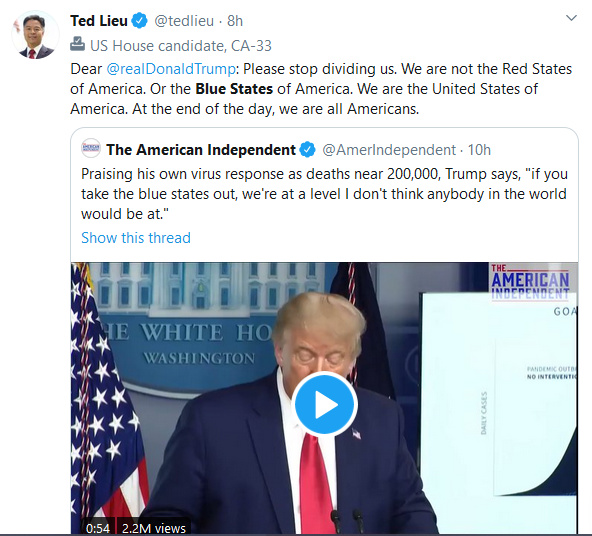

Trump blames ‘blue states’ for increasing nation’s coronavirus death rates, ignores high rates in red states

Trump blames blue states for the coronavirus death toll — but most recent deaths have been in red states

Virginia Democrat blasts Trump’s ‘appalling’ remark about COVID-19 deaths in ‘blue states’