Newly revealed USPS documents show an agency struggling to manage Trump, Amazon and the pandemic

Some top administration officials even hoped to tap the mail service’s vast network — and its unrivaled ability to reach every U.S. Zip code — to help Americans obtain personal protective equipment. The idea originated out of the Department of Health and Human Services, which suggested a pack of five reusable masks be sent to every residential address in the country, with the first shipments going to the hardest-hit areas.

At the time, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had been working on coronavirus guidance that recommended face coverings, a reversal of its previous position, in the face of mounting evidence that people could spread the coronavirus without experiencing symptoms. The Postal Service prepared for the possibility it might be deputized in the effort, drawing up a news release touting that it was “uniquely suited” to help. The service specifically identified Orleans and Jefferson parishes in Louisiana as the first areas to receive face coverings, with deliveries shortly thereafter to King County, Wash.; Wayne County, Mich.; and New York, according to the newly unearthed document, which is labeled a draft.

Before the news release was sent, however, the White House nixed the plan, according to senior administration officials, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to share internal deliberations. Instead, HHS created Project America Strong, a $675 million effort to distribute “reusable cotton face masks to critical infrastructure sectors, companies, healthcare facilities, and faith-based and community organizations across the country.” About 600 million of the 650 million masks ordered have been distributed, according to an HHS spokesperson, including 125 million set aside for schools.

More takes on this:

Powerful ad from Republicans Against Trump on Covid from Olivia Troye who worked w/ Pence and resigned.

C.D.C. Testing Guidance Was Published Against Scientists’ Objections

A controversial guideline saying people without Covid-19 symptoms didn’t need to get tested for the virus came from H.H.S. officials and skipped the C.D.C.’s scientific review process.

A heavily criticized recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last month about who should be tested for the coronavirus was not written by C.D.C. scientists and was posted to the agency’s website despite their serious objections, according to several people familiar with the matter as well as internal documents obtained by The New York Times.

The guidance said it was not necessary to test people without symptoms of Covid-19 even if they had been exposed to the virus. It came at a time when public health experts were pushing for more testing rather than less, and administration officials told The Times that the document was a C.D.C. product and had been revised with input from the agency’s director, Dr. Robert Redfield.

But officials told The Times this week that the Department of Health and Human Services did the rewriting and then “dropped” it into the C.D.C.’s public website, flouting the agency’s strict scientific review process.

“That was a doc that came from the top down, from the H.H.S. and the task force,” said a federal official with knowledge of the matter, referring to the White House task force on the coronavirus. “That policy does not reflect what many people at the C.D.C. feel should be the policy.”

The document contains “elementary errors” — such as referring to “testing for Covid-19,” as opposed to testing for the virus that causes it — and recommendations inconsistent with the C.D.C.’s stance that mark it to anyone in the know as not having been written by agency scientists, according to a senior C.D.C. scientist who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of a fear of repercussions.

Adm. Brett Giroir, the administration’s testing coordinator and an assistant secretary at the Department of Health and Human Services, the C.D.C.’s parent organization, said in an interview Thursday that the original draft came from the C.D.C., but he “coordinated editing and input from the scientific and medical members of the task force.”

Over a period of a month, he said, the draft went through about 20 versions, with comments from Dr. Redfield; top members of the White House task force, Dr. Anthony Fauci and Dr. Deborah Birx; and Dr. Scott Atlas, President Trump’s adviser on the coronavirus. The members also presented the document to Vice President Mike Pence, who heads the task force, Admiral Giroir said.

He said he did not know why the recommendation circumvented the usual C.D.C. scientific review. “I think you have to ask Dr. Redfield about that. That certainly was not any direction from me whatsoever,” he said.

Dr. Redfield could not be reached for comment.

The question of the C.D.C.’s independence and effectiveness as the nation’s top public health agency has taken on increasing urgency as the nation approaches 200,000 deaths from the coronavirus pandemic and Mr. Trump continues to criticize its scientists and disregard their assessments.

A new version of the testing guidance, expected to be posted Friday, has also not been cleared by the C.D.C.’s usual internal review for scientific documents and is being revised by officials at Health and Human Services, according to a federal official who was not authorized to speak to reporters about the matter.

Similarly, a document, arguing for “the importance of reopening schools,” was also dropped into the C.D.C. website by the Department of Health and Human Services in July and is sharply out of step with the C.D.C.’s usual neutral and scientific tone, the officials said.

The information comes mere days after revelations that political appointees at H.H.S. meddled with the C.D.C.’s vaunted weekly reports on scientific research.

“The idea that someone at H.H.S. would write guidelines and have it posted under the C.D.C. banner is absolutely chilling,” said Dr. Richard Besser, who served as acting director at the Centers for Disease Control in 2009.

Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, director of the agency during the Obama administration, said, “H.H.S. and the White House writing scientifically inaccurate statements such as ‘don’t test all contacts’ on C.D.C.’s website is like someone vandalizing a national monument with graffiti.”

The vast majority of C.D.C. documents are still carefully created and vetted and are valuable to the public, but having politically motivated messages mixed in with public health recommendations undermines the institution, Dr. Frieden said. “The graffiti makes the whole monument look pretty bad,” he said.

The current guidelines on testing, posted on Aug. 24, said people without symptoms “do not necessarily need a test” even if they have been in close contact with an infected person for more than 15 minutes. Public health experts roundly criticized the C.D.C. for that stance, saying it would undermine efforts to contain the virus.

“Suggesting that asymptomatic people don’t need testing is just a prescription for community spread and further disease and death,” said Dr. Susan Bailey, president of the American Medical Association, which usually works closely with the C.D.C.

Some experts also said the recommendation appeared to be motivated by a political impetus to make the number of confirmed cases look smaller than it is.

Dr. Redfield later tried to walk back the recommendation, saying testing “may be considered for all close contacts,” but his attempts only added to the confusion. The language on the C.D.C.’s website remained unchanged.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America, normally a close partner of the C.D.C., strongly criticized the recommendation on testing. “We’ve communicated that to the C.D.C. and H.H.S., but I have not seen any signs that they’re going to change it,” said Amanda Jezek, a senior vice president at the organization.

At a congressional hearing on Wednesday, Dr. Redfield said the agency was revising the recommendation and would post the revision, “I hope before the end of the week.” The revision was written by a C.D.C. scientist but was being edited on Thursday by the Department of Health and Human Services and the White House coronavirus task force, according to a federal official familiar with the matter.

Dr. Redfield also said at the Wednesday hearing that vaccines would not be widely distributed till next year and that face coverings were more effective than vaccines — assertions that Mr. Trump sharply criticized in a press briefing Wednesday evening, saying Dr. Redfield “made a mistake.”

The director has been described by C.D.C. employees and outsiders as a weak and ineffective leader who is unable to protect the agency from the administration’s meddling in its science or from the public’s increasing mistrust in the agency.

“It feels like a setup,” the C.D.C. scientist said, adding that many scientists within the agency feel it is being made to take the blame for the administration’s unpopular policies.

“C.D.C. scientists are running scared,” Scott Becker, chief executive of the Association of Public Health Laboratories, said. “There’s nothing they can do that gets them out of this blame game.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has also often been criticized during the pandemic, for being too slow and cautious in issuing recommendations for dealing with the coronavirus. That’s partly because every document is cleared by at least one individual on multiple relevant teams within the agency to ensure the information is consistent with the “current state of C.D.C. data, as well as other scientific literature,” according to a senior agency scientist who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

In all, each document may be cleared by 12 to 20 people within the agency. “As somebody who reads them regularly and as somebody who has written things with C.D.C., I can tell you that the clearance process is painful, but it’s useful,” said Carlos del Rio, an infectious disease expert at Emory University. “It’s very detail oriented and very careful and they, quite frankly, improve the documents.”

At least eight versions of the current testing guidance were circulated within the agency in early August, according to officials. But staff scientists’ objections to the document went unheard. A senior C.D.C. official told the scientists, “We do not have the ability to make substantial edits,” according to an email obtained by The Times. The testing guidance was then quietly published on the agency’s website on Aug. 24.

After the new guidance was published, media inquiries to the agency about its contents were directed to the Department of Health and Human Services, prompting speculation about its origins. C.D.C. scientists were asked to make sure other pages on the website were consistent with the new recommendations. And a “talking points” memo circulated within the agency on Sept. 1 instructed employees to say that the C.D.C. was involved in developing the new guidance “with suggested comments and edits shared back with HHS and the White House Taskforce.”

That sort of instruction would not have been necessary had the document been written by the C.D.C. staff, according to experts familiar with the agency’s procedures. “Never seen that talking point before,” a C.D.C. scientist said.

The recommendation also asked people who “have attended a public or private gathering of more than 10 people (without widespread mask wearing or physical distancing)” to get tested only if they are “vulnerable.” The agency in fact recommends against people congregating in such groups, and its scientists avoid using the term “vulnerable” to describe at-risk groups, according to a C.D.C. scientist familiar with the agency’s procedures.

The guidance is also nested within the section intended for health care workers and labs, but addresses the general public and makes several references to “your health care provider.”

“We just looked so sloppy,” the scientist said. “That’s what kills me is it didn’t come from the inside.”

Experts who work closely with the C.D.C. said the mistakes were obvious.

“You’re used to reading Shakespeare and all of a sudden now you’re reading a tabloid,” Dr. del Rio said. “There was political pressure on C.D.C. in the past, but I think this is unprecedented.”

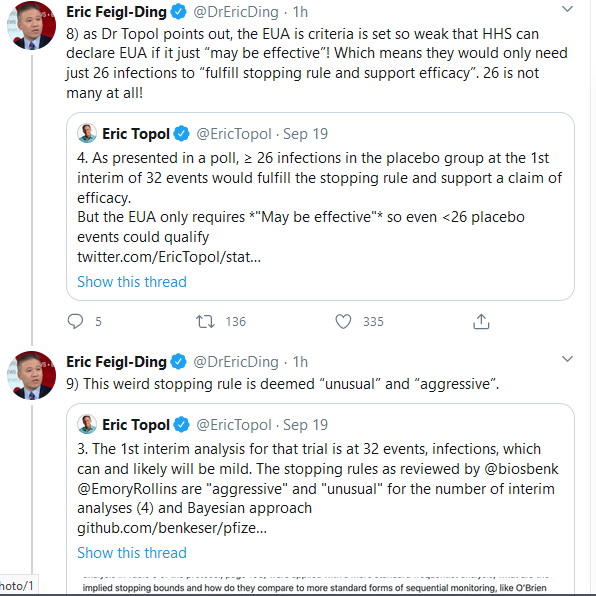

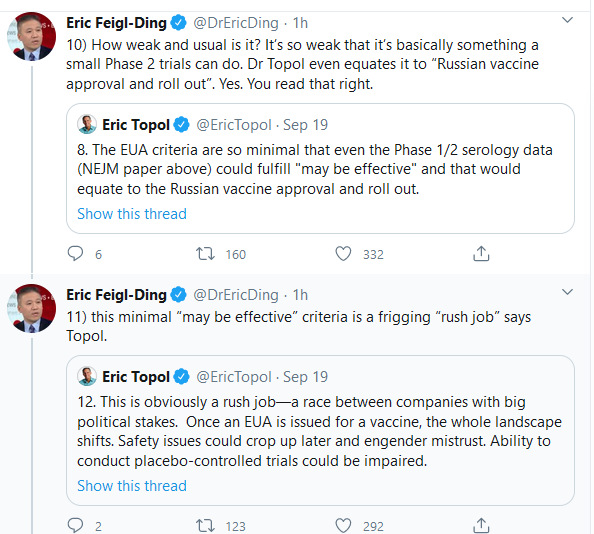

Not only has this BEEN happening, this is going to happen AGAIN tomorrow.

Two articles out about this.

I was watching the Trump/CDC/vaccine/mask BS on PDF and I would just like to say that if Trump is pushing for October he is holding people hostage all wrong. I will eat my hat, okay I don’t have a hat but I’ll buy one just for this, if he doesn’t end up saying the last week in October “yep we’ve got this vaccine, it’s safe and approved, I can get it to everyone fast because I know people, and I’ll totally release it the second week in November. You know, if I’m still around.”

Because 1) he can’t do it safely, and b) if he does it this way it literally doesn’t matter if there’s a vaccine or not. He gets the votes, and if it kills people or is never released at all it doesn’t matter, when the votes are in he keeps power and never has to worry about an election again.

If he tries to look the hero by distributing whatever he can get his hands on in October and it kills a bunch of people that would cost votes, so why wouldn’t he just bluff?

I filter all of what comes out of his mouth…

No argument about how this happening, where to place the blame…sort of know we are so past this point. T will spew anything…and I can not even go there.

But i can go here…

Fauci says he’ll take responsibility if US COVID-19 vaccine is faulty - Business Insider

In an interview published Thursday with Business Insider’s Hilary Brueck, Fauci said he was confident there would be a “safe and effective vaccine” available by the end of 2020.

He told Brueck: "I said November, December — others say October. I think it’s unlikely in October, but maybe, you never know. But let’s say a safe bet will be the end of this calendar year."

The timeline is more cautious than the preelection forecasts given by Trump. Fauci also noted that it would take until sometime in 2021 for most people to actually receive a vaccine even if some doses were ready earlier.

But, in common with his MSNBC interview, Fauci has emphasized that any vaccine rolled out will be safe.

“That’s Their Problem”: How Jared Kushner Let the Markets Decide America’s COVID-19 Fate

First-person accounts of a tense meeting at the White House in late March suggest that President Trump’s son-in-law resisted taking federal action to alleviate shortages and help Democratic-led New York. Instead, he enlisted a former roommate to lead a Consultant State to take on the Deep State, with results ranging from the Eastman Kodak fiasco to a mysterious deal to send ventilators to Russia.

On the evening of Saturday, March 21, a small group of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, business executives, and venture capitalists gathered in the White House Situation Room to offer their help to the Trump administration as it confronted a harrowing shortage of lifesaving supplies to battle COVID-19.

More than seven weeks after the federal government first learned that a new and lethal coronavirus was barreling toward U.S. shores, hospitals were pleading for masks, gloves, and other personal protective equipment to safeguard their medical staff. Intensive care nurses had been photographed wearing garbage bags instead of gowns. More than 19,600 Americans had been diagnosed with the disease, and at least 260 had died.

The meeting’s attendees—some present, some dialing in—were a bipartisan collection of heavy hitters. The ad hoc group had spent weeks canvassing America’s private sector to map the shortages and draft a plan to solve them. Briefly using a hotel ballroom in Washington, D.C., as a makeshift headquarters, they sought answers to some urgent questions: What capacity did America’s companies have to manufacture protective equipment and medical supplies? What supplies could be ordered now? Were there hidden reserves?

They had secured commitments from dozens of major corporations, including General Motors, to manufacture ventilators, map supply needs, create a system for contact tracing, and much more.

On Friday, March 20, they met with a large group of officials at the Federal Emergency Management Agency—people one attendee described as “the doers”—to strategize how best to replenish the nation’s depleted reserves of PPE. The attendees had gotten a significant pledge from, among many others, Mary Barra , the CEO of General Motors. Her company could reconfigure a production line to make ventilators, so long as the federal government would commit to purchasing them. To accomplish that, the private sector attendees and the FEMA officials discussed the need for President Donald Trump to invoke a federal law called the Defense Production Act, which would unleash the government’s procurement powers.

As one attendee recounted, certain government officials there had “implored” the group to return the next day to the White House for a follow-up with President Trump’s son-in-law and senior adviser, Jared Kushner , to make the case for the Defense Production Act. Earlier in the month Kushner had formed a coronavirus “shadow task force” running parallel to the official one helmed by Vice President Mike Pence.

The meeting began at 6:30 p.m. Kushner is an observant Jew and normally wouldn’t work during Shabbat, which ended at 8:00 that evening, but a “rabbinic dispensation” allows him to make exceptions for matters of public importance, according to a senior administration official.

Those representing the private sector expected to learn about a sweeping government plan to procure supplies and direct them to the places they were needed most. New York, home to more than a third of the nation’s coronavirus cases, seemed like an obvious candidate. In turn they came armed with specific commitments of support, a memo on the merits of the Defense Production Act, a document outlining impediments to the private-sector response, and two key questions: How could they best help? And how could they best support the government’s strategy?

According to one attendee, Kushner then began to rail against the governor: “Cuomo didn’t pound the phones hard enough to get PPE for his state…. His people are going to suffer and that’s their problem.”

What actually transpired in the room stunned a number of those in attendance. Vanity Fair has reconstructed the details of the meeting for the first time, based on recollections, notes, and calendar entries from three people who attended the meeting. All quotations are based on the recollections of one or more individual attendees.

Kushner, seated at the head of the conference table, in a chair taller than all the others, was quick to strike a confrontational tone. “The federal government is not going to lead this response,” he announced. “It’s up to the states to figure out what they want to do.”

One attendee explained to Kushner that due to the finite supply of PPE, Americans were bidding against each other and driving prices up. To solve that, businesses eager to help were looking to the federal government for leadership and direction.

“Free markets will solve this,” Kushner said dismissively. “That is not the role of government.”

The same attendee explained that although he believed in open markets, he feared that the system was breaking. As evidence, he pointed to a CNN report about New York governor Andrew Cuomo and his desperate call for supplies.

“That’s the CNN bullshit,” Kushner snapped. “They lie.”

According to another attendee, Kushner then began to rail against the governor: “Cuomo didn’t pound the phones hard enough to get PPE for his state…. His people are going to suffer and that’s their problem.”

“That’s when I was like, We’re screwed,” the shocked attendee told Vanity Fair.

The group argued for invoking the Defense Production Act. “We were all saying, ‘Mr. Kushner, if you want to fix this problem for PPE and ventilators, there’s a path to do it, but you have to make a policy change,’” one person who attended the meeting recounted.

In response Kushner got “very aggressive,” the attendee recalled. “He kept invoking the markets” and told the group they “only understood how entrepreneurship works, but didn’t understand how government worked.”

Though Kushner’s arguments “made no sense,” said the attendee, there seemed to be little hope of changing his mind. “It felt like Kushner was the president. He sat in the chair and he was clearly making the decisions.”

Kushner was accompanied by Navy Rear Admiral John Polowczyk , who had just been posted to FEMA to lead supply-chain efforts. He heaped flattery on Kushner, calling his ideas “brilliant,” and expressed skepticism concerning the motives of those in the room and on the phone. “Are you trying to hawk your wares on us?” he asked one participant.

Ultimately, there was little follow-up from the government on the group’s offers. President Trump invoked the Defense Production Act in name a week later, but he didn’t immediately use the act to formally order supplies, sparking confusion and delays. He also rage-tweeted at Barra, the CEO of GM: “Always a mess with Mary B.” The government waited until April 8 to announce its first order of ventilators from GM.

“We had so much potential to commandeer against this,” said one person who attended the meeting. “We had a real system for contact tracing, the world’s best mobile engineers on standby. There was a real opportunity to have a coordinated response.”

That attendee said he remains “angry” over the federal government’s intransigence in stockpiling supplies and feels certain that people died because of it. “At the time I just thought of it as blind capitalism and extreme libertarian ideals gone wrong,” he said. “In hindsight it’s not crazy to think it was some purposeful belief that it was okay if Cuomo had a tough go of it because [New York] was a blue state.”

According to another attendee, it seemed “very clear” Kushner was less interested in finding a solution because, at the time, the virus was primarily ravaging cities in blue states: “We were flabbergasted. I basically had an out-of-body experience: Where am I, and what happened to America?”

In response to a request for comment, a senior administration official told Vanity Fair that the meeting was not confrontational and said the attendees’ impressions were “not rooted in reality.” He said the federal government had sourced “over a billion items of PPE, enough ventilators so that no American was denied one, and we are the leading testing country in the world.” He added that the “vast majority of the federal response was aimed at helping blue states,” and pointed to public statements Governor Cuomo had made, in which he said Kushner had been “extraordinarily helpful.”

White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany had this to say: “This story is another inaccurate and disgusting partisan hit job. President Trump has consistently put the health of all Americans first.”

At the end of July, writing for Vanity Fair, I revealed that Kushner had commissioned a robust federal COVID-19 testing plan, only to abandon it before it could be implemented. One public health expert in frequent contact with the White House’s official coronavirus task force said a national plan likely fell out of favor in part because of a disturbingly cynical calculation: “The political folks believed that because [the virus] was going to be relegated to Democratic states, that they could blame those governors, and that would be an effective political strategy.”

The story struck a nerve, partly because it painted a picture of what might have been: The administration could have invested in a national testing system at a scale that could have greatly limited the number of cases and deaths. Instead the U.S. is on track to pass the grim milestone of 200,000 official COVID-19 deaths this month. With just 4% of the world’s population, we now account for 20% of global deaths from the virus.

After the story was published, I pressed on with my reporting, hoping to learn more about Kushner’s operation. I also wanted to better understand how the U.S., with its advanced medical systems, unmatched epidemiological know-how, and vaunted regulatory and public health institutions, could have fumbled the crisis so disastrously.

Part of the answer almost certainly lies in the deep-seated belief, held by Kushner, President Trump, and their loyalists, that the federal government not only should not, but cannot play an effective leading role in responding to the pandemic, owing to its lumbering bureaucracy and onerous rules. At almost each step they have ignored the expertise of career officials and dismissed those with relevant experience as counterproductive meddlers. Trump famously calls them the Deep State. (A senior administration official denied this, saying, “The administration worked diligently to combine the best of the federal government and the private sector.”)

Though even a well-coordinated federal response would have posed extreme challenges, it could have followed a well-marked trail. Early on President Trump could have unleashed the vast procurement powers of the federal government. The Defense Production Act, a Korean War–era law, allows the president to direct U.S. businesses to manufacture supplies—and gives the federal government first dibs on buying them. It was an obvious solution to a crisis that threatened the life of every American citizen.

“When the military needs to buy planes and make bullets, [it doesn’t] rely on the invisible hand of the free market,” said Jeremy Konyndyk , a senior policy fellow at the Center for Global Development who helped lead the Obama administration’s response to the 2014 Ebola outbreak. It uses the Defense Production Act, “because it’s urgent,” he said.

But as experts watched and waited, Trump shied away from invoking the act—which he later deployed haphazardly. (A senior administration official said President Trump has invoked the Defense Production Act “dozens of times when appropriate.”) Instead he put his faith in the entrepreneurial instincts of his son-in-law. And Kushner wasn’t interested in a big government solution.

Kushner set out to reinvent what a response might look like, countering the Deep State with what you might call a Consultant State of his own creation. This might have been a worthwhile experiment had it not taken place in the context of a once-in-a-century public health catastrophe. As it is, it has led to organizational chaos, futile misadventures, and, most tellingly, a steadily climbing death rate. Often communicating using the encrypted platform WhatsApp, with little adherence to public records laws or federal contracting guidelines, Kushner and a tight-knit group of allies he’s recruited have overseen a response riddled with special favors and political calculation. When they managed to procure lifesaving equipment, they used the surplus to shore up the president’s relationship with Russia, hijacking a foreign aid agency in the process. And when they made a deal to bring drug manufacturing home to the United States, it blew up amid accusations of financial fraud.

“What you have going on here is smoke and mirrors,” said Larry Hall , who retired last year as director of the Defense Production Act program division at FEMA. “You do not have a national strategy.”

From the beginning of his involvement in the pandemic, Kushner set about sidelining government experts in favor of young, untested volunteers drawn from consulting firms and investment banks like McKinsey and Goldman Sachs. Using personal emails and working under nondisclosure agreements, the volunteers were supposed to use their private sector savvy to source leads on protective equipment, then turn those leads over to the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

They operated at the direction of a former Goldman Sachs analyst and 2014 Princeton University graduate named Rachael Baitel , who’d previously worked as a special assistant to Ivanka Trump at the White House. Before getting into finance she’d also worked as a denim intern at Ralph Lauren. Baitel’s group eventually spawned its own whistleblower, who alleged in a letter to a congressional subcommittee that the group maintained a spreadsheet titled “V.I.P. Update” that gave priority to tips from political allies and friends, according to reports in the New York Times and Washington Post .

A senior administration official involved in the task force said the young financial analysts provided an efficient solution to an unprecedented problem: Dubious leads on supplies were flooding in from around the world. “In the first tier of a venture capital firm, you receive incoming calls from your investment firm. You vet them, you prequalify them.” Those volunteers were able to “step through the mishmosh” and figure out the leads to pursue.

The journalist Duff McDonald , author of The Firm: The Story of McKinsey and Its Secret Influence on American Business , said it’s common for private sector CEOs to use management consultants as a crutch when they are out of their depth—and don’t want to be blamed for what goes wrong. “Kushner is at a loss for how to stall what is happening, so he’s doing the classic ‘analyst punt,’” McDonald said, “going to his pals at McKinsey instead of people in the Deep State who can do their jobs today. These are people who think, If you have a quantitative grasp, you can manage anything. I have no doubt that they’re telling Kushner he’s a genius as well.”

One attorney who worked at a private company that conferred with the government on procuring PPE described the Kushner team’s interactions with colleagues as “off the books, completely irregular.” The attorney said a common refrain from Baitel was, “We have to figure out a way around this”—“this” being the government-procurement laws that Kushner and his team believed were an obstacle to quick action. Their strategy, the lawyer said, amounted to: “Call the people we see at Davos and have them go get stuff for us.”

Some career officials within the so-called Deep State view Kushner and his deputies with intense skepticism, referring to them derisively as the “Slim-Suit Crowd.” One of the most prominent members of the Slim-Suit Crowd is a man who, in a White House that values loyalty above all else, seems to have the ultimate credential: He roomed with Kushner for a summer in the NYU dorms, when they were both college students interning at different investment banks. Kushner later attended his wedding.

On March 12, the day after Vice President Pence pulled Kushner into the pandemic response, Kushner reached out to his old friend Adam Boehler , who was serving in the administration as the CEO of the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, a newly created development bank within the federal government tasked with making loans overseas.

Tapping Boehler was not a terrible idea. Formerly a health care executive, he had founded an innovative start-up called Landmark Health, which brought primary care to the homes of underserved, chronically ill patients. Andy Slavitt , a former Obama administration health care official who has served as a sounding board for Boehler, told me, “This is a guy who can work 20 hours a day. If he gets one more ventilator to save one more life, that’s the name of the game.”

But to some of the besieged health care officials who began fielding his directives, Boehler was a government neophyte and an unaccountable agent of chaos. They felt the same way about Baitel, who became his deputy chief of staff at the DFC. Boehler approached the pandemic response like a management consultant looking to slash red tape. He shared Trump and Kushner’s quasi messianic belief in the private sector’s ability to respond effectively to the crisis and their contempt for government capabilities. On April 30, Boehler appeared as a guest on the podcast run by Michael Milken , the American financier who pleaded guilty to securities and tax violations in 1990 and was pardoned by Trump three decades later. “My job has been to bring public and private together and to work to drive very quick action,” Boehler said.

Boehler described public–private partnerships as “a big focus of the president, Jared, and me.” He added, “We get asked all the time: How come we’re not throwing Defense Production Act orders all over the place? … It’s not necessary when you have the private market taking all the right actions to support Americans.”

In reality the private sector not only needed, but wanted federal leadership. “Everyone involved was begging for the federal government to figure out the needs, make a very big order at a very fair price, and scientifically figure out how to distribute PPE,” said a software company CEO who worked on the pandemic response. Those in private industry trying to procure supplies did not want to bid against fellow Americans in need or act as distributors. “We don’t want to decide who lives and who dies,” the CEO said. In a bidding war without federal guidance, “everyone is going to overbuy and overpay. That is the definition of the tragedy of the commons. Everyone accidentally creates a worse outcome for everybody.”

Boehler made it clear that he viewed agencies like FEMA, with their deep reserves of experience, as too slow and cumbersome to respond to the pandemic. “FEMA is set up to respond to hurricanes,” as he told Milken. But the coronavirus is like “hurricanes in every one of the 50 states and the two territories at the same time.”

When it comes to the pandemic response, Boehler has become Kushner’s key aide-de-camp. He has had a hand in everything from the aborted testing plan in April to the push in late August to approve convalescent plasma therapy over the objections of officials at the National Institutes of Health, including Dr. Anthony Fauci . According to some colleagues and friends, Boehler is just the kind of person you’d want involved in the government’s response. Kushner “wisely recognized that Adam Boehler knows a lot about health care,” said Dr. Bob Kocher , partner at the health care venture capital firm Venrock, who helped overhaul California’s system for COVID-19 diagnostic testing and interacted with Boehler during that work.

For all his talents, however, Boehler’s track record leaves much to be desired. A survey of initiatives bearing his fingerprints reveals that, at a time when Americans desperately needed a large-scale intervention to protect the health of the most vulnerable among us, he and Kushner expended valuable time on political favors and blame-shifting exercises.

Not much about the White House response to the COVID-19 pandemic went according to plan, but the Trump administration did succeed in one venture: stockpiling ventilators. Even if congressional investigators later found that a deal struck by trade adviser Peter Navarro to buy 43,000 ventilators from a Dutch company cost the U.S. Treasury half a billion dollars more than it should have.

By the end of April, unfortunately, the medical community had determined that ventilated COVID-19 patients often had worse outcomes than patients who were simply given supportive oxygen. With the machines falling out of favor among doctors, the U.S. found itself in possession of a surplus. The question then became: What to do with them?

The U.S. Agency for International Development, known as USAID, is headquartered two blocks south of the White House, at 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue. Traditionally, USAID has focused on such humanitarian pursuits as battling starvation, protecting vulnerable populations from deadly diseases, and supporting democratic transitions. In 2016 alone, according to its website, the agency helped feed more than 53 million people in 47 different countries. In late May 2020, its staffers were busy aiding Uzbekistan after a dam collapse and helping governments in Africa manage COVID-19 outbreaks.

So it came as a surprise when, without explanation, USAID got a new and urgent mission at the direction of the White House’s National Security Council. On May 20, an exasperated USAID official, Peter Mamacos , shared the news in a Skype meeting of government officials: The agency had been instructed to ship more than 200 ventilators to Russia, according to notes taken by a participant on the call, which Vanity Fair has obtained. Furthermore, the delivery had to be prioritized over any of the agency’s other work.

The order had been relayed from President Trump to his chief of staff, Mark Meadows , who then routed it through the National Security Council. The directive came just days after a May 7 phone call between Trump and Vladimir Putin. “USAID was given no discretion in any of this,” said one government official with knowledge of the directive. “It was deemed a priority to give vents to Russia.”

Over the following weeks officials at USAID scrambled to fulfill the mysterious order. Doing so pulled resources and staff hours away from the agency’s core humanitarian mission, and came at the expense of poorer countries with far more limited resources.

This was especially hard to swallow when the ask itself looked like a political favor. When USAID officials objected, they were told by NSC staffers, “These decisions are being made at the White House,” according to the official with knowledge of the demand. More specifically, they were told that Boehler was “the one calling the shots.”

The urgent order disrupted USAID’s detailed plans to ship ventilators to dozens of other countries. Russia “seemed to be first in line” and “got prioritized ahead of a lot of other countries,” said the government official with knowledge of the demand.

This was no simple mail drop either. The ventilators, a number of which had proprietary parts, had to be reconfigured to work with Russian power sources. That expensive and time-consuming extra step was doubly ironic to those who recalled that, on April 1, Russia had delivered 45 ventilators to the United States without bothering to refit them for American power sources. They were the same type of faulty ventilator believed to have sparked fires in Russian hospitals.

The total cost of sending the ventilators to Russia was $3.46 million, but that doesn’t account for the impact on morale at an agency whose staff signed up to help the poor, not to perform a favor for a strategic rival flush with oil money. (In response to a request for comment, a senior administration official said, “At the time, the COVID-19 outbreak was worsening in Russia, which had the second-highest number of cases in the world and the highest number of cases in Europe. In response to President Putin’s request for assistance, President Trump offered to donate and deliver 200 ventilators to the Russian people.” A second senior administration official, who was involved in the efforts, said, “All international ventilator efforts, to dozens of countries, were decided by an interagency group that included NSC, State, and USAID.”)

Both Democratic and Republican members of a Senate Appropriations subcommittee that oversees USAID’s spending reportedly objected to the ventilator shipment. As one Democratic congressional aide put it, “It was inexplicable and a bad idea for the administration to do this as a favor to Putin, but USAID was forced to by the White House.”

Of all the aborted efforts to secure America’s supply chain of essential lifesaving supplies, no deal has blown up more spectacularly than the one to turn an aging camera film company, Eastman Kodak, into an American manufacturer of ingredients for low-cost generic drugs. It was overseen by Boehler in his official role as CEO of the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation.

The DFC is effectively a government lending bank that was established in 2019 by combining two entities, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) and the Development Credit Authority, previously housed in USAID. It was born out of a rare bipartisan interest in countering China’s influence around the globe, but under Boehler’s leadership, the agency’s priorities have mystified government bureaucrats—and disappointed members of the foreign-development corps that worked to create it in the first place. Boehler “doesn’t have a development agenda,” said one former Trump administration official who is an expert in international development work. “He has an Adam agenda.”

In late April government officials preparing for the upcoming G20 summit in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and the G7 summit, which has been postponed, were instructed by a White House assistant to insert language about the DFC into pandemic-preparedness documents that would be shared with foreign ministers.

Given the long-standing prohibition against naming specific programs or projects in G20 materials, the requested language—an infomercial of sorts for the DFC—baffled and troubled officials. The language stated: “The Development Finance Corporation, and U.S. Export Import Bank, an incentive fund, will establish a clear role for engagement with U.S. private sector firms, faith-based organizations, and international entrepreneurs.”

After a back-and-forth among officials from the Departments of State, Treasury, and Health and Human Services, the language was struck. One official familiar with the discussions said, “We are exceedingly careful because we don’t know what in the blazing [hell] DFC is. We find it inserted in the most bizarre places.”

On May 14, President Trump signed an executive order that essentially transferred the powers of the Defense Production Act to Boehler directly, allowing the CEO of the DFC to bolster “the domestic production of strategic resources needed to respond to the COVID-19 outbreak, or to strengthen any relevant domestic supply chains.” The executive order gave Kushner’s former roommate access to $100 million of the $1 billion allocated to the Department of Defense under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to bolster domestic supply chains.

Boehler’s first announcement under the order, on July 28, was a splashy press event announcing a letter of interest to grant a $765 million loan to Eastman Kodak in order for it to remake itself as a manufacturer of pharmaceutical ingredients and return drug making to U.S. shores.

The deal’s origins had been far less ambitious, Vanity Fair has learned. In late March, shortly after President Trump first declared from the White House podium that an old malaria drug, hydroxychloroquine, could be a game changer in the treatment of COVID-19, an Eastman Kodak executive reached out to officials at the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority. The executive asked if the film company could “donate some of their manufacturing capability/capacity” to the cause of addressing chloroquine shortages, a BARDA official told a colleague, according to an email obtained by Vanity Fair. (Hydroxychloroquine eventually fell out of favor after studies found it to be ineffective against COVID-19 and potentially hazardous to patients.)

By mid-April, Kodak, which has a large chemical plant in Rochester, New York, was circulating a relatively modest proposal to the Food and Drug Administration and BARDA, which Vanity Fair has obtained, seeking $15.3 million in federal support to make raw materials for hydroxychloroquine. That amount would “address the gap between current market prices in India and China compared to the costs associated with producing this intermediate within the United States,” the proposal stated.

https://news.yahoo.com/why-u-covid-19-response-073341005.html

Idaho pastor who prayed against mask mandate is in intensive care with coronavirus

“It has been clearly and scientifically proven that many masks do not aid in the prevention of Covid-19 transmission,” Pastor Paul Van Noy said in July.

Most of the US is headed in the wrong direction again with Covid-19 cases as deaths near 200,000

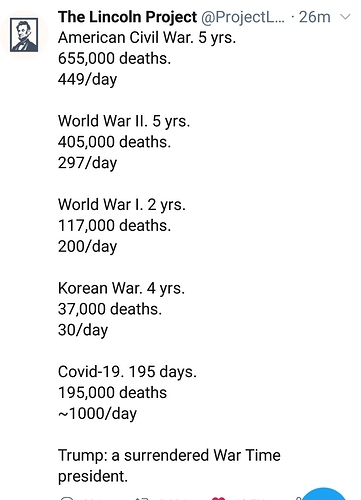

American causalities ranked by loss

-

American Civil War (1861-65) 618,222

-

WW2 (1941-45) 291,557

-

Covid-19 (February-September 2020) 200,000

-

WW1 (1917–18) 53,402

-

Vietnam War (1955–75) 47,424

-

Korean War (1950–53) 33,686

-

American Revolutionary War (1775–83) 8,000

Well fuck.

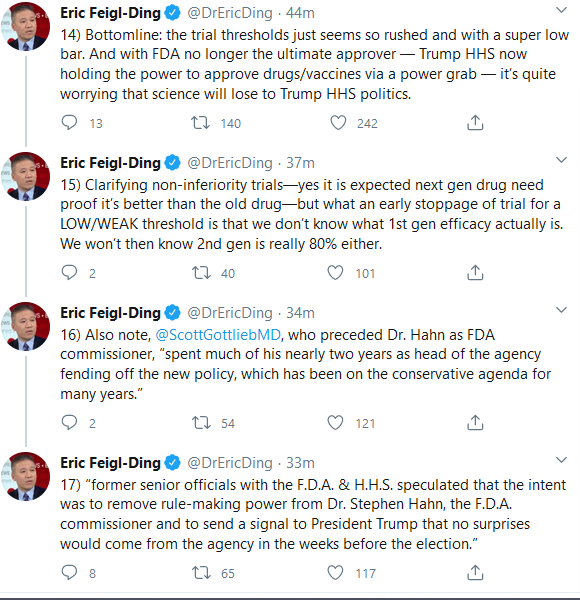

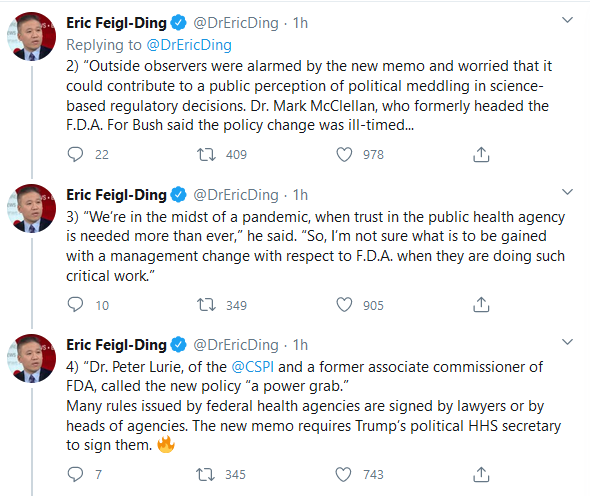

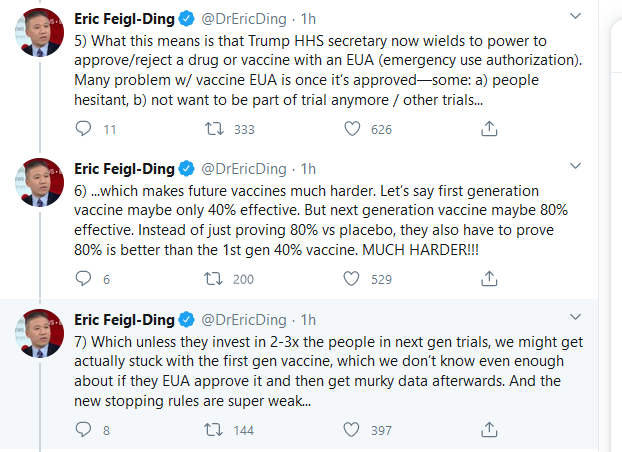

In ‘Power Grab,’ Health Secretary Azar Asserts Authority Over F.D.A.

Experts said the memo would make it more difficult for the F.D.A. to issue new rules, but it’s unclear how it would affect the vetting of coronavirus vaccines.

A Notorious COVID Troll Actually Works for Dr. Fauci

William B. Crews is, by day, a public affairs specialist for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. But for years he has been writing for RedState under the streiff pseudonym. And in that capacity he has been contributing to the very same disinformation campaign that his superiors at the NIAID say is a major challenge to widespread efforts to control a pandemic that has claimed roughly 200,000 U.S. lives.

Under his pseudonym, Crews has derided his own colleagues as part of a left-wing anti-Trump conspiracy and vehemently criticized the man who leads his agency, whom he described as the “attention-grubbing and media-whoring Anthony Fauci.” He has gone after other public health officials at the state and federal levels, as well—“the public health Karenwaffen,’’ as he’s called them—over measures such as the closures of businesses and other public establishments and the promotion of social distancing and mask-wearing. Those policies, Crews insists, have no basis in science and are simply surreptitious efforts to usurp Americans’ rights, destroy the U.S. economy, and damage President Donald Trump’s reelection effort.

Medicare Wouldn’t Cover Costs of Administering Coronavirus Vaccine Approved Under Emergency-Use Authorization

Lawmakers in March passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, or Cares Act, which ensures free coronavirus vaccine coverage, including no out-of-pocket costs for people on Medicare. But Medicare doesn’t cover costs for drugs approved under emergency-use designations.

The Food and Drug Administration authorizes certain drugs for emergency use to provide speedy access to treatments for serious diseases during a health crisis. Standards for emergency-use authorization aren’t as high as they are for its typical drug approvals.

Trump administration officials recently came to the conclusion that Medicare’s exclusion of emergency-use drug costs could leave millions of people paying out-of-pocket for vaccines the government intends to make free, according to three people familiar with the matter. About 44 million people, or about 15% of the U.S. population, are covered by Medicare.

The Department of Health and Human Services is exploring coverage options for a Covid-19 vaccine approved under an emergency-use authorization, and any vaccine doses bought by the government will be provided at no cost, an HHS spokeswoman said.

The White House is pushing to get a vaccine as early as next month that would be approved by the FDA under an emergency-use authorization. The White House didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

The White House and HHS may press Congress to change the language in the Cares Act so that it includes Medicare coverage for a vaccine approved under an emergency-use authorization, according to a senior administration official familiar with the matter. But administration officials are worried about whether the changes can be accomplished in time for a possible October vaccine rollout, the official said.

The problem can’t be fixed with an executive order, the official said, so HHS is also looking at whether any creative interpretation of existing regulations could allow for Medicare coverage for administering the vaccine.

The White House will have to go back to Congress if they want the vaccine to be available to the 44 million Medicare patients.

Battle royale ver 2020…this and a million other fixes right…and T just wants to make themselves look good. So this to be negotiated…hmmmm a bargaining chip, right?

CDC reverses itself and says guidelines it posted on coronavirus airborne transmission were wrong

Agency removes statement, claiming website error

https://www.cnbc.com/2020/09/21/coronavirus-live-updates.html

Basically MORE CDC reversals. The CDC had finally admitted Friday the virus is airborne.

And now they deleted that.

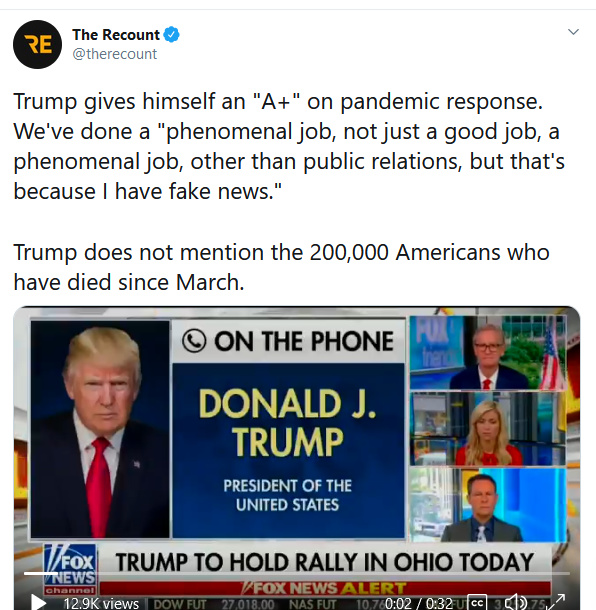

Donald Trump gives himself an ‘A+’ for his handling of the coronavirus. Uh, what?

How did President Donald Trump commemorate this remarkable loss of life? This way:

“We’re rounding the corner,” he told “Fox & Friends” of the coronavirus during an interview Monday morning. “With or without a vaccine. They hate when I say that but that’s the way it is. … We’ve done a phenomenal job. Not just a good job, a phenomenal job. Other than public relations, but that’s because I have fake news. On public relations, I give myself a D. On the job itself, we take an A+.”

“A phenomenal job.”

“A+.”

Trump Says He Deserves An ‘A+’ For His Handling Of The Coronavirus Pandemic

Trump calls his handling of pandemic ‘phenomenal’ as US death toll nears 200K

He gave himself a “D” grade on what he called “public relations” and blames the “Fake News.”

President Donald Trump on Monday gave himself an “A+” grade on his handling of the coronavirus pandemic, saying he and his administration had done a “phenomenal job” even as the death toll neared 200,000 Americans.

At the same time, he gave himself a “D” on what he called “public relations.”

“We’ve done a phenomenal job. Not just a good job. A phenomenal job. Other than public relations, but that’s because I have fake news, you know, I can’t – you can’t convince them of anything, they’re a fake. But we have done – on public relations, I give myself a D," he said in a phone interview on “Fox and Friends.”