Pulled out a few details from that article, this would effectively end asylum in the US.

Here are just a few examples of the numerous changes to U.S. asylum law and policies included in the proposal:

- Categorically deny claims where the applicant suffered persecution on account of gender. If implemented, this rule would rewrite long-standing legal precedent and shut the door to safety for women and girls fleeing rape, domestic violence and sexual abuse. Government statistics don’t break down the numbers, but those of us working in the field know that a large proportion of female asylum seekers have escaped this kind of persecution. Just this month, the International Rescue Committee reported that gender-based violence in Latin America has increased exponentially since the pandemic.

- Allow immigration judges to deny asylum applications without a court hearing and testimony from the applicant . This means judges can decide if a case has merit based on the written application alone. Asylum law is notoriously complex, and the 12-page application form is confusing and filled with legalese. Such a change will be nearly fatal for the tens of thousands of asylum seekers who have no lawyer to help them with their claim in court. Data shows that those with a lawyer are already five times more likely to win asylum than those without one. Without a hearing, applicants disadvantaged by language and literacy challenges as well as the effects of trauma will face nearly insurmountable obstacles.

- Create new barriers to obtaining asylum for anyone who attempts to enter the United States unlawfully, passes through more than one country before arriving here, works in the United States without authorization or fails to pay taxes, among other provisions. By penalizing those without the resources to secure a visa, or expecting all applicants to travel by direct flight, or demanding that they forgo working to feed their families (asylum applicants must wait 150 days before they can seek employment authorization), the Trump administration is creating a system that is actively hostile to the lived realities of most asylum seekers.

These and the nearly dozen other proposals would apply to anyone seeking asylum in the United States, regardless of how, where and when they enter the country. This includes the 866,858 individuals, including children, who have already applied for asylum and are awaiting a hearing or interview to present their cases. Once implemented, the cumulative effect of these rules will be to effectively rewrite the refugee definition out of existence and end asylum in the United States. Those who stand to suffer from these proposals include our neighbors, our classmates, our friends, our relatives and the many essential workers putting their lives on the line during the pandemic.

‘We sit in disbelief’: the anguish of families torn apart under Trump’s deportation policy

Many American families struggle with steep financial decline after a breadwinner’s deportation as Trump broadened targets to include immigrants with no serious criminal records

Before her husband was deported, Seleste Hernandez was paying taxes and credit card bills. She was earning her way and liking it.

But after her husband, Pedro, was forced to return to Mexico, her family lost his income from a commercial greenhouse job. Seleste had to quit her nursing aide work, staying home to care for a disabled son. Now she is trapped, grieving for a faraway spouse and relying on public assistance just to scrape by.

She went, in her eyes, from paying taxes to depending on taxpayers. “I’m back to feeling worthless,” she says.

Across the country, hundreds of thousands of American families are coping with anguish compounded by steep financial decline after a spouse’s or parent’s deportation, a more enduring form of family separation than Donald Trump’s policy that took children from parents at the border.

Trump has broadened the targets of deportation to include many immigrants with no serious criminal records. While the benefits to communities from these removals are unclear, the costs – to devastated American families and to the public purse – are coming into focus. The hardships for the families have only deepened with the economic strains of the coronavirus.

According to a new Marshall Project analysis with the Center for Migration Studies, just under 6.1 million American citizen children live in households with at least one undocumented family member vulnerable to deportation.

About 331,900 American children have a parent who has legal protection under Daca, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the center’s analysis found. After the supreme court ruled last Thursday that Trump’s cancellation of Daca was unlawful, those families are still protected from deportation, for now. But the court’s ruling allows Trump to try to cancel the program again. And the debate cast light on 10.7 million undocumented immigrants living in the United States, who remain exposed to Trump’s enforcement.

Nationwide, about 908,891 households with at least one American child would fall below federal poverty levels if an undocumented breadwinner was removed, according to the analysis by the center, a research organization in New York affiliated with the Catholic church.

After a breadwinner is deported, many families that once were self-sufficient must rely on social welfare programs to survive. With the trauma of a banished parent, some children fail in schools or require expensive medical and mental health care. With family savings depleted, American children struggle financially to stay in school or attend college.

Seleste Hernandez is now the sole caregiver for her 30-year-old son Juan, barely able to haul his 140-pound frame from his bed to his wheelchair. Her family and two others in north-eastern Ohio, a region where Trump’s deportations have taken a heavy toll, have borne the costs of these expulsions.

They are part of a large and growing group of American households hit by deportation. From 2013 to 2018, more than 231,000 immigrants who were deported said they had American citizen children, according to the most recent data available from Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or Ice.

But despite his tough talk, Trump’s record on deportations is mixed. Under his administration the numbers have climbed, reaching 337,287 deportations in 2018 – the latest figures available – but still well below the peak of 432,281 set by President Barack Obama in 2013, according to Department of Homeland Security statistics.

Yet under Trump, any immigrant without legal status is vulnerable, after he reversed a 2014 Obama administration directive that instructed Ice to concentrate on removing immigrants convicted of serious crimes. In each year under Trump the number of deportees with no criminal convictions has increased, from 98,420 in 2017 to 117,117 in 2019 – 43% of all deportations last year, according to Ice reports.

Many of those recorded as criminals are immigrants whose crime was to cross the border without documents. According to the most recent data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 85% of immigrants arrested on federal charges in 2018 – a total of 105,748 arrests – were accused of immigration crimes, mainly entering the country illegally.

Ice officials say their strategy is working to make communities safer because they are taking lawbreakers off the streets.

“These individuals, they’re here illegally and they’re committing crimes,” said Matthew Albence, the senior official serving as director of Ice, at a press conference earlier this year. “The crime rate should be zero because the people here illegally shouldn’t be here to begin with.”

Back in 2004, when Seleste Wisniewski met Pedro Hernandez in her hometown of Elyria, she was a harried single mother from Ohio’s battered working class, raising three children, including a son with severe cerebral palsy.

But Hernandez was not put off. He won her heart, she said, by bringing her a ripe watermelon instead of flowers, to show her his pride in his farming skills.

He moved in. Pedro went to his greenhouse job in the early morning. Seleste, a nursing assistant for the elderly, worked at night. They alternated the care of her son Juan, who doesn’t talk and can’t eat or move on his own. Together Pedro and Seleste had a son, Luis, now 11.

In 2013, Pedro was stopped by local police for a broken license plate light. Instead of settling for a ticket, the police turned him over to the border patrol. Twelve years earlier, he had been deported after crossing the border without papers, so the border patrol deported him again. Determined to get back to his family, he crossed again illegally. But immigration agents arrested him soon after he returned home in July 2013. This time they charged him with illegal re-entry, a federal felony, hoping to send him to prison.

When Pedro was led in handcuffs into a federal courtroom in Cleveland, Juan, in a wheelchair, let out an agitated cry. The judge and the prosecutor said they were surprised to learn that Pedro was supporting a family member with a disability. They quickly agreed to dismiss the criminal case, court records show.

By then Obama was discouraging Ice from expelling immigrants with no criminal convictions. Pedro was granted a stay of deportation. For the next four years, according to his case file, he checked in regularly with Ice. He received a work permit, and with that he got a driver’s license, a full-time job growing poinsettias at a local greenhouse, even a 401K retirement account. He and Seleste got married. Her application for his permanent resident green card was approved.

In a letter to his lawyer, Ice officials said Pedro was officially off their list of priorities for deportation.

That changed under Trump. On 8 August 2017, Ice agents went to the Hernandez home, ordering Pedro to leave by 30 September.

“You got something wrong,” Seleste insisted. “What has changed?”

There is a new president and a new administration, an agent told her.

“Sir, we’re still the same family,” she protested. “We’re doing everything we were supposed to.”

An Ice spokesman, Khaalid Walls, said the agency had acted because Pedro was a “repeat immigration violator”. On 28 September he was put aboard a flight to Mexico. At the door of the plane, Ice officers handed him a notice: he was barred from returning for 20 years.

“We were getting there,” Seleste said, between hurt and rage. “We’re almost there. And then, boom, get out. And I’m left to put the pieces together.”

These days Pedro is farming a corn patch in the mountains above Acapulco, scratching out just enough to eat. Seleste is home with Juan, who requires regular feeding through a stomach tube, and someone to be near him at all times.

When both Pedro and Seleste were working, they made about $4,300 a month, enough to buy groceries, pay bills and buy Pedro a red pickup truck. They paid taxes and had health insurance through their employers.

Now Seleste draws on public services to survive. After she had to leave her job, the household income dropped to zero, and her housing subsidy, part of Juan’s disability assistance, soared from $90 to $811 a month, with the county now paying her entire rent. She receives $509 a month in food stamps.

She lost her private health insurance and is on Medicaid. She was paid $1,200 from the federal coronavirus stimulus.

“Pedro was a contributor,” said Father Charlie Diedrick, the priest at St Mary’s church in Elyria, where Luis attends school. “He took care of his family and his neighbors. And we put an end to that.”

Seleste organizes her day around four or five fleeting conversations by WhatsApp, when Juan is calmed by hearing Pedro’s voice from Mexico. With the coronavirus threatening his frail health, Juan can never leave the house. Pandemic travel restrictions have cut Luis off from his summer visit to his father.

“Only thing I know is me, my kids, we sit in disbelief, struggling,” Seleste said. “Unnecessary suffering of the separation. Unnecessary worry. Is the country a safer place?”

In November 2017, Esperanza Pacheco went to the Ice office in Cleveland for a regular check-in. She was detained and never came out. A week later, she was dropped by Ice in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico.

“We never got to say goodbye, nothing,” said Thalia Moctezuma, her American daughter, who was 18 and a high school senior at the time.

The north-east Ohio town of Painesville, where Pacheco lived, has been an epicenter of enforcement under Trump. Since 2017 Ice has been tracking down undocumented people in town and cancelling stays, leading to dozens of deportations. Many immigrants, under pressure, packed up and left on their own.

“What you see now is a community that is very demoralized,” said Veronica Dahlberg, executive director of HOLA, an immigrant advocacy group in Painesville.

Pacheco, a vivacious woman with an infectious giggle, is one of 14 children of a Mexican bracero farmworker who years ago became a US citizen. He applied for citizenship for all his children. But due to bureaucratic errors and delays, only Pacheco’s naturalization never went through.

In more than two decades in the United States, she married another Mexican, Eusebio Moctezuma, now a legal resident, and had four daughters born in Ohio. Pacheco had one blot on her record, from a day in 2002 when she left two of the girls, just toddlers, alone in her trailer home to run to a job interview. A neighbor called the police, and Pacheco drew a misdemeanor conviction for endangering a child.

Ten years later, under Obama, Ice threatened to deport her. Advocates mobilized. Her daughters marched in Painesville streets. Ice desisted, granting a deportation stay and a work permit. By 2017 Pacheco’s oldest daughter was about to turn 21 and was ready to present a new petition for a green card for her mother.

Then Trump took office. Fifteen years after Pacheco’s maternal lapse, Ice officials pointed to that offense to categorize her as a criminal and justify deporting her, separating her from her daughters.

The girls were cast adrift. Their father had to work extra hours at his landscaping construction job to pay the bills and could rarely be home.

“When mom was here, she was cooking, talking, everything was right,” Eusebio said one morning in the kitchen of the family’s ramshackle trailer, his mood despondent. “I thought I was OK to handle my daughters. But now I find out they need mom over here. She’s the one that makes us a family together.”

Pacheco landed in a walk-up apartment in her old hometown of León, Guanajuato. She tries to console her husband and raise her daughters by WhatsApp, messaging them throughout the day.

For her daughters, it’s not the same. “In our house, I feel that vibe where it’s cold, it’s just dark,” Thalia said. “It feels like a place but not a home.”

Not long after Pacheco’s deportation, kids in the girls’ schools took to taunting them.

“They started saying, your mom’s illegal, you should have gone back to Mexico, you’re not really from here,” Eusebio said.

One daughter, M., who was 17, lashed out, getting into fistfights in the hallways. (The Marshall Project is not using the full names of the younger daughters because they were minors when their mother was deported.)

M. began missing classes and drinking a mix of vodka and beer before school. A year after the deportation, Thalia came home one night to find M. passed out on the floor, foaming at the mouth, a bottle of sleeping pills by her side. She called Pacheco and turned around her phone to show her mother that M. was unconscious.

“I wanted to fly to them, but I couldn’t do anything,” Pacheco said in a phone interview from León. Suppressing panic, she instructed Thalia on the video call how to keep M. alive and find a relative to rush her to a hospital.

M. spent a week in Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital in Cleveland, and she went to a rehab center for another week.

“We asked her why she did that and she said, because she feels so lonely, she needed mom,” Eusebio said, his voice thick with sorrow. “They are so very close to mom.”

After M. recovered, her outlook changed. She graduated from high school, got a job, and was talking of going to college, even law school.

But the youngest daughter, M. D., struggled. In August 2019 she went to visit her mother in Mexico. The girls often felt torn returning from those visits, realizing they loved their mother but did not want to live with her in Mexico. M. D. begged her mother to come with her to the United States.

“Baby, I’ll be there soon,” Pacheco said, knowing it wasn’t true.

Not long after, M. D., then 15, swallowed 60 pills of ephedrine. Her medical chart on 25 September of last year, the day she entered Rainbow Hospital, stated that she was “currently admitted due to suicide attempt with ingestion”. It noted that she “has attempted to overdose 3 prior times in last 3 months”.

Doctors observed that M. D. had spurts of abnormally fast heartbeat, a result of the overdose. After two weeks in the hospital and an in-patient mental health center, on 9 October she went back to Rainbow for four more days for a procedure to repair her heart.

Thalia found a diary M. D. had kept. She hated her life, she wrote, because her school friends had their mothers at home and were happy, and she didn’t have hers. Do we deserve this? she asked. Why us?

By March, M. D. was back taking her classes and the family was stabilizing. But as the coronavirus crippled the economy, their financial situation was already dire.

Eusebio, who was making $3,500 a month at his job, lost more than $7,000 when he missed work caring for his daughters in the hospital. When Pacheco was home, she brought in at least $350 a week cooking Mexican specialties to sell to neighbors. Now the family has to send Pacheco $100 a month to pay her rent. Three of the sisters are working instead of going to college, to keep the family afloat.

Rainbow Hospital, and the private University Hospitals system it is part of, absorbed almost the entire cost of the medical care for both girls. The family was uninsured. Eusebio received no bills for either girl’s emergency care, so the total cost is unclear. He paid out $500 for an ambulance for M. D. and $720 for her psychiatric treatment. Rainbow did send a bill for $9,800 for M. D.’s cardiac procedure, with instructions for a payment plan. Eusebio has not been able to pay anything yet.

He was out of work for a month with the pandemic lockdown. The family has not sought federal assistance, fearing it could hurt Pacheco’s green card application, her only hope of returning to her family.

On the other end of a mobile app, Pacheco fights desperation. “I’m Mexican,” she said, “but I hope God hears me, I don’t want to be here in Mexico.”

Alfredo Ramos had been living in the United States for nearly a decade when he met Susan Brown, an American from a blue collar family in Painesville. She was 20 at the time and a single mother. They had a joyful courtship of raucous parties and walks in the woods.

Brown became pregnant, and in 2000 she and Ramos married. But when she was in her ninth month, Ice raided the factory where Ramos was working and deported him. Two weeks later Brown, lonely and frantic without her husband, gave birth to their son, Cristian.

“I did what everybody would want to do in that situation,” Brown said. She sent Ramos $2,000 to pay a smuggler to help him cross the border illegally. He was back a few weeks later.

Brown’s family rejoiced. “I knew he wouldn’t just walk away from a child being born,” said Jessica Brown, Susan’s sister. “We are a family that knows right from wrong. But we believed there would be a pathway for him to something legal.”

Because of Ramos’s deportation, the legal pathway proved hard to find. Two years later, a daughter, Diona, was born. To make ends meet, Brown worked two jobs and Ramos took any work he could find, but his wages stayed low because of his undocumented status. Over time, tensions arose. Ramos and Brown divorced.

But he remained a hands-on provider, at times taking both children to live with him in a cramped Painesville apartment. “Maybe we weren’t hugging and stuff like that, but I would always know he was there for me,” Cristian said.

In March 2014, Ramos was a passenger in a vehicle that was pulled over for a minor traffic stop by local police. The officers demanded his immigration papers. They turned him over to Ice.

A pattern was repeated: Ice tried to convict Ramos in federal court for an illegal entry crime. His children chanted support for their father outside the courthouse in Erie, Pennsylvania. The federal prosecutor dismissed the case “in the interests of justice”. Ice relented, issuing a stay.

After that the children grew even closer to their father. Of his times spent with Ramos, Cristian said, “I just wanted it always to be this way.”

But shortly after Trump took office, Ice agents cancelled the stay and came looking for Ramos. After a month on the run from house to house in Painesville, he summoned his children. He would leave before Ice deported him, he said, so he would have a chance of returning legally to be with them someday.

Beaming in on FaceTime from a family homestead, also in León, Ramos invariably showed a smile. But on 4 September 2018, a relative called from Mexico. Ramos had been executed with 27 shots by a drug gang, who mistook him for a rival trafficker. His children watched the funeral by video.

Cristian decided he could not afford college and enlisted in the Navy. Diona just graduated from high school, a track star whose final season of competition was suspended by the pandemic. A scholarship she won to the University of Kentucky will partially pay her tuition, but loans will have to do the rest.

Brown cannot help them, as she just manages to pay her own bills working in an aerospace parts factory, still going in every day during the pandemic even though she is at risk, since she has debilitating diabetes. She cannot identify a benefit from Ramos’s expulsion.

But she has no difficulty assessing the irreparable cost: “Two children who are American citizens lost their father.”

Trump’s immigration policies are not merely racist, isolationist, and xenophobic; they’re bad for business, particularly technology, science, and higher education, all of which thrive on influx and sharing of talent from other nations.

In fact, the U.S. role as the melting pot of the world is what MADE us the technological and industrial giant we are. And now we’re losing that edge.

Businesses, Colleges Plead With Trump To Preserve Work Visas

Gregory Minott came to the U.S. from his native Jamaica more than two decades ago on a student visa and was able to carve out a career in architecture thanks to temporary work visas.

Now a U.S. citizen and co-founder of a real estate development firm in Boston, the 43-year-old worries that new restrictions on student and work visas expected to be announced as early as this week will prevent others from following a similar path to the American dream.

“Innovation thrives when there is cultural, economic and racial diversity,” Minott said. “To not have peers from other countries collaborating side by side with Americans is going to be a setback for the country. We learned from Americans, but Americans also learn from us.”

Minott is among the business leaders and academic institutions large and small pleading with President Donald Trump to move cautiously as he eyes expanding the temporary visa restrictions he imposed in April.

They argue that cutting off access to talented foreign workers will only further disrupt the economy and stifle innovation at a time when it’s needed most. But influential immigration hard-liners normally aligned with Trump have been calling for stronger action after his prior visa restrictions didn’t go far enough for them.

Trump, who has used the coronavirus crisis to push through many of his stalled efforts to curb both legal and illegal immigration, imposed a 60-day pause on visas for foreigners seeking permanent residency on April 22. But the order included a long list of exemptions and didn’t address the hundreds of thousands of temporary work and student visas issued each year.

Republican senators, including Tom Cotton of Arkansas and Ted Cruz of Texas, argue that all new guest worker visas should be suspended for at least 60 days or until unemployment has returned to normal levels.

“Given the extreme lack of available jobs,” the senators wrote in a letter to Trump last month, “it defies common sense to admit additional foreign guest workers to compete for such limited employment.”

Trump administration officials have been debating how long the forthcoming order should remain in place and which industries should be exempted, including those working in health care and food production.

But the White House has made it clear it’s considering suspending H-1B visas for high-skilled workers; H-2B visas for seasonal workers and L-1 visas for employees transferring within a company to the U.S.

In recent weeks, businesses and academic groups have also been voicing concern about possible changes to Optional Practical Training, a relatively obscure program that allows some 200,000 foreign students — mostly from China and India — to work in the country each year.

Created in the 1940s, OPT authorizes international students to work for up to one year during college or after graduation. Over the last decade, the program has been extended for those studying science, technology, engineering and mathematics so that they can now work for up to three years.

While congressional Republicans have been some of the strongest supporters of eliminating the program, 21 GOP House lawmakers argued in a letter to the Trump administration this month that OPT is necessary for the country to remain a destination for international students. They said foreign students and their families pump more than $40 billion annually into the economy even though the students represent just 5.5.% of U.S. college enrollments.

Companies and academic institutions also warn of a “reverse brain drain,” in which foreign students simply take their American education to benefit another nation’s economy.

Some critics say OPT gives companies a financial incentive to hire foreigners over Americans because they don’t have to pay certain federal payroll taxes.

The program also lacks oversight and has become a popular path for foreigners seeking to gain permanent legal status, said Jessica Vaughan, policy director at the Center for Immigration Studies, a Washington group advocating for strict immigration limits.

“The government does not require that there be actual training, and no one checks on the employer or terms of employment,” she said. “Some of the participants are career ‘students,’ going back and forth between brief graduate degree programs and employment, just so they can stay here.”

Xujiao Wang, a Chinese national who has been part of the program for the past year, said she doesn’t see any fault in trying to build her family’s future in the U.S.

The 32-year-old, who earned her doctorate in geographic information science from Texas State University, is working as a data analyst for a software company in Milford, Massachusetts.

She’s two months pregnant and living in Rhode Island with her husband, a Chinese national also working on OPT, and their 2-year-old American-born daughter. The couple hopes to eventually earn permanent residency, but any change to OPT could send them back to China and an uncertain future, Wang said.

“China is developing fast, but it’s still not what our generation has come to expect in terms of freedom and choice,” she said. “So it makes us anxious. We’ve been step-by-step working towards our future in America.”

In Massachusetts, dismantling OPT would jeopardize a fundamental part of the state’s economy, which has been among the hardest hit by the pandemic, said Andrew Tarsy, co-founder of the Massachusetts Business Immigration Coalition.

The advocacy group sent a letter to Trump last week pleading for preservation of the program. It was signed by roughly 50 businesses and colleges, including TripAdvisor and the University of Massachusetts, as well as trade associations representing the state’s thriving life sciences industry centered around Harvard, MIT and other Boston-area institutions.

“We attract the brightest people in the world to study here, and this helps transition them into our workforce,” Tarsy said. “It’s led to the founding of many, many companies and the creation of new products and services. It’s the bridge for international students.”

Minott, the Boston architect, argues that the time and resources required to invest in legal foreign workers, including lawyers’ costs and visa processing fees, exceeds any tax savings firms might enjoy.

DREAM Collaborative, his 22-person firm, employs three people originally hired on OPT permits who are now on H-1B visas — the same path that Minott took early in his career.

“These programs enabled me to stay in this country, start a business and create a better future for my family,” said the father of two young American-born sons. “My kids are the next generation to benefit from that, and hopefully they’ll be great citizens of this country.”

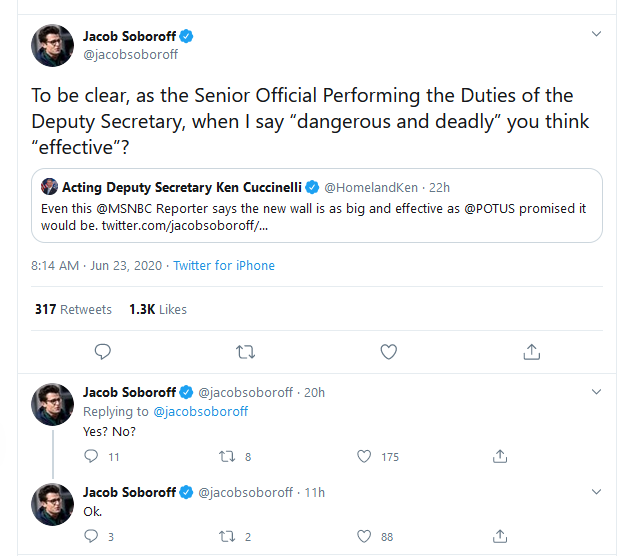

And here we have acting DHS deputy secretary Ken Cuccinelli gaslighting by twisting a reporter’s statement on Trump’s racist border wall. Why the hell is he still acting? Because Trump knows it lets him get away with more atrocities.

The White House Is Quietly Deporting Children

The Trump administration is flouting the law to turn away minors in desperate need of protection.

Please add to and refresh Immigration:

I find it very hard to believe these are only the first cases. ICE has been deporting immigrants infected with COVID-19 for months.

ICE reports first coronavirus cases among detained migrant families with children

US immigration agency prepares to furlough more than half of its workforce

The federal agency charged with granting immigration benefits, processing visa applications and approving citizenship is preparing to furlough more than half of its workforce unless Congress provides additional funding, according to a spokesperson.

US Citizenship and Immigration Services notified Congress of its projected budget shortfall last month. While conversations with the Hill are ongoing, according to the agency’s statement, preparation is underway for furloughs.

Approximately 13,400 employees will be notified whether they’ll be furloughed beginning August 3, an agency spokesperson said. The agency has nearly 20,000 employees.

Government must release migrant children in detention centers because of coronavirus, judge orders

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement must release children held in the country’s three family detention centers by July 17 because of the danger posed by the coronavirus pandemic, a federal judge in Los Angeles ordered.

U.S. District Judge Dolly Gee said in a ruling Friday that children held for more than 20 days at ICE family residential centers should be released by July 17 to “non-congregate settings” that include “suitable sponsors” and even to their own parents, who can also be released if conditions warrant it.

The entire U.S. immigration system is about to shut down.

Exactly as Trump wants.

The Immigration System Is Set To Come To A Near Halt, And No One Is Paying Attention

“It essentially will shut down the immigration system — sort of the final nail in the coffin.”

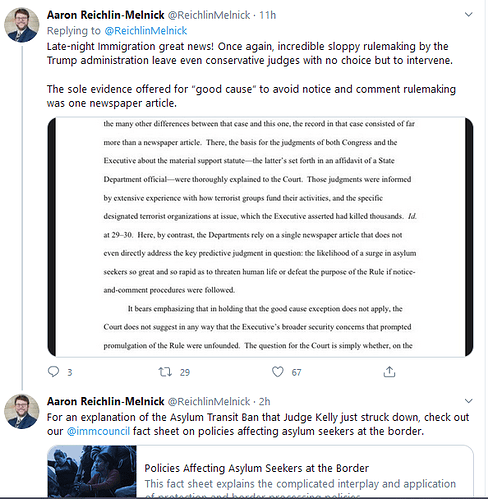

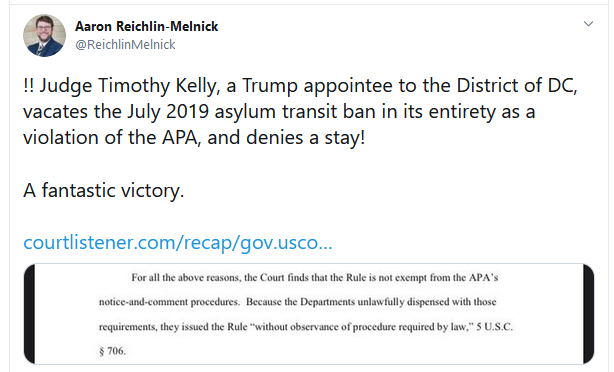

Another Trump loss in the courts:

They want to bar asylum seekers because of coronavirus, even if they caught the disease in a US detention center. This can’t be legal.

What is really despicable is that WE caused many of those outbreaks. I have a whole thread on how we’ve been forcing Central American and Caribbean nations to take deportees or we deny them aid, but we’re sending them people who are infected, often packed in with those who are not, directly CAUSING the issues they need aid against! Several nations have refused to accept flights any longer.

In looking up the issue above I found this:

New Proposed Asylum Regulations Would Endanger Women’s Lives

Women and girls fleeing forms of extreme abuse that mostly targets women—such as rape, female genital mutilation (FGM), forced and child marriage, human trafficking, and severe domestic violence—have always faced an uphill battle in securing asylum protection in the United States. After decades of strategic litigation, female asylum-seekers have made important legal gains. But new rules proposed by the Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Justice would obliterate that progress.

The recently proposed regulations would eliminate legal protection for the vast majority of asylum-seekers fleeing persecution in their homelands and seeking protection in the United States. For women and girls fleeing gender-based persecution, these rules are problematic in two significant ways. First, they arbitrarily limit the ability of women to present claims based on gender-based persecution or gender-specific political opinion. Second, the regulations would also include procedural barriers for women presenting claims that involve gender-based persecution, which are already more difficult to present.

The rules appear designed to eliminate gender-based persecution claims. Under these new rules, for example, even a Yazidi survivor of rape perpetrated as part of the Islamic State’s genocidal attacks in Iraq would face significant hurdles to securing protection.

The 1951 Refugee Convention defines a refugee as “a person who, owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable, or owing to such fear is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.” The drafters did not include “gender” as a protected ground, likely because the male drafters did not recognize the role of the state in sanctioning violence against women through state laws and policies. Yet today, the Guidelines on International Protection issued by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) recognize that women can constitute a “particular social group.”

Because gender was not included as a protected ground under the Refugee Convention, claims involving gender-based persecution are frequently presented under the category of “membership of a particular social group.” In 1985 in Matter of Acosta , the Board of Immigration Appeals defined a particular social group as having common and immutable characteristics that “members of the group either cannot change, or should not be required to change because it is fundamental to their individual identities or consciences.” Sex was among the examples provided—and so Matter of Acosta was a critical case for women fleeing gender persecution.

These legal developments continued after Matter of Acosta . In the 1996 case Matter of Kasinga . the Board of Immigration Appeals decided that a young woman from Togo who fled FGM qualified for asylum protection, writing that she was a member of a particular social group “consisting of young women of the Tchamba Kunsuntu Tribe who have not had FGM, as practiced by that tribe, and who oppose the practice.” The Kasinga case set precedent for gender-persecution claims countrywide.

But under the new asylum regulations proposed by the Trump administration, the asylum applicant in Kasinga would likely find her claim denied. Here’s why: under asylum law, a person must show that she was persecuted on account of one of the five protected grounds set out in the Refugee Convention, also called the “nexus requirement.” One of the proposed rules would significantly curtail gender as forming part of the nexus required to establish persecution on account of a protected ground. The proposed rule identifies “gender” as one of eight circumstances in which the secretary of homeland security and the attorney general will not favorably adjudicate asylum based on persecution, barring rare circumstances that are not defined. Therefore, Fauziya Kasinga could establish that she was a member of a particular social group “consisting of young women of the Tchamba Kunsuntu Tribe who have not had FGM, as practiced by that tribe, and who oppose the practice” but under the new rule would be unlikely to establish that she feared persecution on account of a protected ground, because the particular social group includes “women” or “gender.”

Coming back to the example of a Yazidi survivor of Islamic State captivity who was clearly targeted for sexual violence and enslavement based on her gender, this woman would be unable to qualify for asylum on account of membership in a particular social group that includes gender.

In 2018, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions constrained asylum claims based on severe domestic violence in the case of Matter of A-B- . In that case, Sessions used his authority over immigration courts to overrule Matter of A-R-C-G —a case where the Board of Immigration Appeals recognized domestic violence as a basis for asylum protection. The proposed regulations would codify this ill-advised decision and prevent women from stating claims involving domestic violence.

Ironically, in rules proposed in late 2019, the departments of Justice and Homeland Security proposed seven new asylum bars for those “who commit federal, state, tribal, or local domestic violence offence, or who are found by an adjudicator to have engaged in acts of battery or extreme cruelty in a domestic context, even if no convicted resulted ” (emphasis added). If both rules are adopted, asylum adjudicators could determine that someone perpetrated domestic violence to bar him from asylum and then turn around to deny asylum for a victim of domestic violence.

Also problematic is how the rule would seriously narrow the definition of “political opinion” to include only activities in “furtherance of political control of a state or unit thereof.” Political opinion has long been held to be expansive and encompass fighting against communism as well as China’s one-child policy. The rule would narrowly define political opinion within the realm of anti-state action. This would exclude cases where women hold or express a political opinion about women’s rights, including the view that men do not have the right to beat or rape their wives. If this rule is adopted, cases where women are persecuted because of their political beliefs about gendered structural inequalities may no longer succeed.

There are many proposed rules that change asylum procedures in ways that significantly impair access to protection. For reasons of expediency, the proposed rule would streamline cases that include asylum, withholding of removal, and withholding of removal under the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT). Asylum-seekers would be deprived of legal remedies that currently exist for individuals who are in removal proceedings pursuant to the Immigration and Nationality Act § 240 (8 U.S.C. § 1229a). This is important because, as people wait for their cases to move forward, changes can occur in their lives that would make them eligible for other forms of relief—such as the U nonimmigrant visa for victims of crime, the T nonimmigrant visa for victims of trafficking, or adjustment of status based on marriage.

The pretermit rule would allow a judge to make a legal determination of an asylum case based only on a written application, and the judge could deny an application if the applicant did not present a viable claim on paper. The rule permits a judge to ask for additional evidence, giving the asylum applicant “up to 10 days” to respond. This is insufficient time to respond to a request for information regardless of whether someone is represented by an attorney or files pro se. Once denied, the applicant is denied her day in court. It is hard to emphasize how detrimental this change would be to asylum-seekers, as testimony is generally the most compelling evidence in an asylum case. I have witnessed women and men convince adjudicators based on powerful and detailed in-person accounts of persecution.

Applying for asylum without a lawyer is incredibly difficult. The law is complicated, and it is virtually impossible for most people to use the proper legal language when articulating why they fear being sent back to their countries where they face persecution. It is important to remember that because asylum-seekers have often faced past persecution, they may suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder—which can inhibit their ability to remember traumatic events and cause them to appear to lack credibility. This can make it difficult for pro se asylum-seekers to clearly explain past persecution if they are limited to an application without the opportunity to testify.

These proposed rules lose sight of the purpose of asylum law in the U.S. and internationally: to protect individuals from persecution. A person who establishes she is a refugee is presumed to qualify for asylum protection. Yet these proposed regulations take an inverted approach that first seeks to exclude individuals even when they establish that they meet the definition of a refugee. The result will be that many individuals who would normally qualify for protection under the current law will be denied for peripheral reasons unrelated to the core elements of a prima facie asylum case. Once the rules are published and become law, the only recourse for asylum-seekers will be litigation.

Having represented women and girls filing asylum and refugee claims both in the U.S and overseas—and working with Yazidi women and young girls who were abducted and brutally trafficked by the Islamic State—I have seen firsthand the many barriers they face in achieving protection in their own countries. Persecuted people look to the U.S. and other countries to give them an opportunity to escape horrific violence and try to recover and rebuild their lives. While achieving refugee or asylum protection has always been difficult, the fact that it exists gives these women and those who help them hope. If the doors keep closing, many women will receive the message that their lives do not matter.

How the Trump administration is turning legal immigrants into undocumented ones

In mid-June, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services’ contract ended with the company that had been printing these documents. Production was slated to be insourced, but “the agency’s financial situation,” USCIS said Thursday, prompted a hiring freeze that required it to ratchet down printing.

Of the two facilities where these credentials were printed, one, in Corbin, Ky., shut down production three weeks ago. The other facility, in Lee’s Summit, Mo., appears to be operating at reduced capacity.

Some 50,000 green cards and 75,000 other employment authorization documents promised to immigrants haven’t been printed, USCIS said in a statement. The agency said it had planned to escalate printing but that it “cannot speculate on future projections of processing times.” In the event of furloughs — which the agency has threatened if it does not get a $1.2 billion loan from Congress — “all agency operations will be affected.”

Some of the missing green cards are for immigrants newly approved for legal permanent residency. Others are for existing permanent residents who periodically must renew their identity cards, which expire every 10 years but sometimes must be replaced sooner (for example, if lost). These immigrants have completed every interview, required biometric assessment, cleared other hurdles — and often waited years for these critical credentials.

Refusing to even print the green cards… that’s not legal guys.

An investigative report from the NYT and The Marshall Project about how ICE transported Covid-19 positive immigrants back to their respective countries on commercial airlines, and no masks provided, but temperatures were taken. Over 40K immigrants were sent back in this time period to 11 different countries.

All followed CDC guidelines they said…

An investigation by The New York Times in collaboration with The Marshall Project reveals how unsafe conditions and scattershot testing helped turn ICE into a domestic and global spreader of the virus — and how pressure from the Trump administration led countries to take in sick deportees.

We spoke to more than 30 immigrant detainees who described cramped and unsanitary detention centers where social distancing was near impossible and protective gear almost nonexistent. “ It was like a time bomb,” said Yudanys, a Cuban immigrant held in Louisiana.

At least four deportees interviewed by The Times, from India, Haiti, Guatemala and El Salvador, tested positive for the virus shortly after arriving from the United States.

So far, ICE has confirmed at least 3,000 coronavirus-positive detainees in its detention centers, though testing has been limited.

We tracked over 750 domestic ICE flights since March, carrying thousands of detainees to different centers, including some who said they were sick. Kanate, a refugee from Kyrgyzstan, was moved from the Pike County Correctional Facility in Pennsylvania to the Prairieland Detention Facility in Texas despite showing Covid-19 symptoms. He was confirmed to have the virus just a few days later.

“I was panicking,” he said. “I thought that I will die here in this prison.”

We also tracked over 200 deportation flights carrying migrants, some of them ill with coronavirus, to other countries from March through June. Under pressure from the Trump administration and with promises of humanitarian aid, some countries have fully cooperated with deportations.

El Salvador and Honduras have accepted more than 6,000 deportees since March. In April, President Trump praised the presidents of both countries for their cooperation and said he would send ventilators to help treat the sickest of their coronavirus patients.

So far, the governments of 11 countries have confirmed that deportees returned home with Covid-19.

ICE Offering ‘Citizens Academy’ Course with Training on Arresting Immigrants

Imagine hundreds of entitled, angry, racist George Zimmermans unleashed and empowered by Stephen Miller and Donald Trump’s new gestapo.

This is bad, very very bad. Like another step towards genocide bad. At this point the Administration doesn’t want to kill immigrants but sure don’t seem to care if they live either.

Indeed. It’s like Trump watched Police Academy: Citizens on Patrol and thought, “how can I apply this in real life, but with more racism and death and fearmongering and less comedy and zany antics and Steve Guttenberg?”

~10,000 children were stolen from their families by our government, some have died in custody and yet the media has to constantly debunk conspiracy theories about online cabinets for sale and pizza parlors. People can’t even see what’s happening before their very eyes.

This is how genocide happens.