I’ve figured out a trick for the NYT that works for a handful of other sites, and I have a WaPo account. The paywalls can get frustrating these days.

Donald Trump will do anything to be re-elected. His opponents are limited because they believe in democracy. Trump has no limits because he doesn’t.

Here’s Trump’s re-election playbook, in 25 simple steps:

Thousands of U.S. judges who broke laws or oaths remained on the bench

In the past dozen years, state and local judges have repeatedly escaped public accountability for misdeeds that have victimized thousands. Nine of 10 kept their jobs, a Reuters investigation found – including an Alabama judge who unlawfully jailed hundreds of poor people, many of them Black, over traffic fines.

Judge Les Hayes once sentenced a single mother to 496 days behind bars for failing to pay traffic tickets. The sentence was so stiff it exceeded the jail time Alabama allows for negligent homicide.

Marquita Johnson, who was locked up in April 2012, says the impact of her time in jail endures today. Johnson’s three children were cast into foster care while she was incarcerated. One daughter was molested, state records show. Another was physically abused.

“Judge Hayes took away my life and didn’t care how my children suffered,” said Johnson, now 36. “My girls will never be the same.”

Fellow inmates found her sentence hard to believe. “They had a nickname for me: The Woman with All the Days ,” Johnson said. “That’s what they called me: The Woman with All the Days . There were people who had committed real crimes who got out before me.”

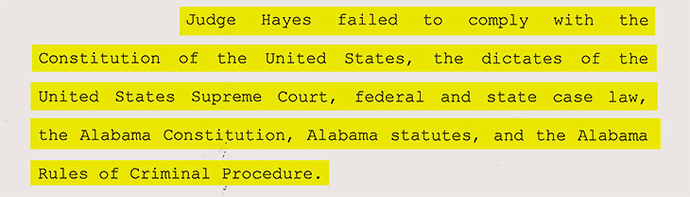

In 2016, the state agency that oversees judges charged Hayes with violating Alabama’s code of judicial conduct. According to the Judicial Inquiry Commission, Hayes broke state and federal laws by jailing Johnson and hundreds of other Montgomery residents too poor to pay fines. Among those jailed: a plumber struggling to make rent, a mother who skipped meals to cover the medical bills of her disabled son, and a hotel housekeeper working her way through college.

Hayes, a judge since 2000, admitted in court documents to violating 10 different parts of the state’s judicial conduct code. One of the counts was a breach of a judge’s most essential duty: failing to “respect and comply with the law.”

Despite the severity of the ruling, Hayes wasn’t barred from serving as a judge. Instead, the judicial commission and Hayes reached a deal. The former Eagle Scout would serve an 11-month unpaid suspension. Then he could return to the bench.

Until he was disciplined, Hayes said in an interview with Reuters, “I never thought I was doing something wrong.”

This week, Hayes is set to retire after 20 years as a judge. In a statement to Reuters, Hayes said he was “very remorseful” for his misdeeds.

Community activists say his departure is long overdue. Yet the decision to leave, they say, should never have been his to make, given his record of misconduct.

“He should have been fired years ago,” said Willie Knight, pastor of North Montgomery Baptist Church. “He broke the law and wanted to get away with it. His sudden retirement is years too late.”

Hayes is among thousands of state and local judges across America who were allowed to keep positions of extraordinary power and prestige after violating judicial ethics rules or breaking laws they pledged to uphold, a Reuters investigation found.

Related content

Judges have made racist statements, lied to state officials and forced defendants to languish in jail without a lawyer – and then returned to the bench, sometimes with little more than a rebuke from the state agencies overseeing their conduct.

Recent media reports have documented failures in judicial oversight in South Carolina, Louisiana and Illinois. Reuters went further.

In the first comprehensive accounting of judicial misconduct nationally, Reuters reviewed 1,509 cases from the last dozen years – 2008 through 2019 – in which judges resigned, retired or were publicly disciplined following accusations of misconduct. In addition, reporters identified another 3,613 cases from 2008 through 2018 in which states disciplined wayward judges but kept hidden from the public key details of their offenses – including the identities of the judges themselves.

All told, 9 of every 10 judges were allowed to return to the bench after they were sanctioned for misconduct, Reuters determined. They included a California judge who had sex in his courthouse chambers, once with his former law intern and separately with an attorney; a New York judge who berated domestic violence victims; and a Maryland judge who, after his arrest for driving drunk, was allowed to return to the bench provided he took a Breathalyzer test before each appearance.

The news agency’s findings reveal an “excessively” forgiving judicial disciplinary system, said Stephen Gillers, a law professor at New York University who writes about judicial ethics. Although punishment short of removal from the bench is appropriate for most misconduct cases, Gillers said, the public “would be appalled at some of the lenient treatment judges get” for substantial transgressions.

Among the cases from the past year alone:

In Utah, a judge texted a video of a man’s scrotum to court clerks. He was reprimanded but remains on the bench.

In Indiana, three judges attending a conference last spring got drunk and sparked a 3 a.m. brawl outside a White Castle fast-food restaurant that ended with two of the judges shot. Although the state supreme court found the three judges had “discredited the entire Indiana judiciary,” each returned to the bench after a suspension.

In Texas, a judge burst in on jurors deliberating the case of a woman charged with sex trafficking and declared that God told him the defendant was innocent. The offending judge received a warning and returned to the bench. The defendant was convicted after a new judge took over the case.

“There are certain things where there should be a level of zero tolerance,” the jury foreman, Mark House, told Reuters. The judge should have been fined, House said, and kicked off the bench. “There is no justice, because he is still doing his job.”

Judicial misconduct specialists say such behavior has the potential to erode trust in America’s courts and, absent tough consequences, could give judges license to behave with impunity.

“When you see cases like that, the public starts to wonder about the integrity and honesty of the system,” said Steve Scheckman, a lawyer who directed Louisiana’s oversight agency and served as deputy director of New York’s. “It looks like a good ol’ boys club.”

That’s how local lawyers viewed the case of a longtime Alabama judge who concurrently served on the state’s judicial oversight commission. The judge, Cullman District Court’s Kim Chaney, remained on the bench for three years after being accused of violating the same nepotism rules he was tasked with enforcing on the oversight commission. In at least 200 cases, court records show, Judge Chaney chose his own son to serve as a court-appointed defense lawyer for the indigent, enabling the younger Chaney to earn at least $105,000 in fees over two years.

NEPOTISM BY WATCHDOG: While serving on a state board on judicial misconduct, Judge Kim Chaney violated the very nepotism rules he enforced on other judges, appointing his own son to more than 200 cases in his hometown.

In February, months after Reuters repeatedly asked Chaney and the state judicial commission about those cases, he retired from the bench as part of a deal with state authorities to end the investigation.

Tommy Drake, the lawyer who first filed a complaint against Chaney in 2016, said he doubts the judge would have been forced from the bench if Reuters hadn’t examined the case.

“You know the only reason they did anything about Chaney is because you guys started asking questions,” Drake said. “Otherwise, he’d still be there.”

Bedrock of American justice

State and local judges draw little scrutiny even though their courtrooms are the bedrock of the American criminal justice system, touching the lives of millions of people every year.

The country’s approximately 1,700 federal judges hear 400,000 cases annually. The nearly 30,000 state, county and municipal court judges handle a far bigger docket: more than 100 million new cases each year, from traffic to divorce to murder. Their titles range from justice of the peace to state supreme court justice. Their powers are vast and varied – from determining whether a defendant should be jailed to deciding who deserves custody of a child.

Each U.S. state has an oversight agency that investigates misconduct complaints against judges. The authority of the oversight agencies is distinct from the power held by appellate courts, which can reverse a judge’s legal ruling and order a new trial. Judicial commissions cannot change verdicts. Rather, they can investigate complaints about the behavior of judges and pursue discipline ranging from reprimand to removal.

Few experts dispute that the great majority of judges behave responsibly, respecting the law and those who appear before them. And some contend that, when judges do falter, oversight agencies are effective in identifying and addressing the behavior. “With a few notable exceptions, the commissions generally get it right,” said Keith Swisher, a University of Arizona law professor who specializes in judicial ethics.

Others disagree. They note that the clout of these commissions is limited, and their authority differs from state to state. To remove a judge, all but a handful of states require approval of a panel that includes other judges. And most states seldom exercise the full extent of those disciplinary powers.

As a result, the system tends to err on the side of protecting the rights and reputations of judges while overlooking the impact courtroom wrongdoing has on those most affected by it: people like Marquita Johnson.

Reuters scoured thousands of state investigative files, disciplinary proceedings and court records from the past dozen years to quantify the personal toll of judicial misconduct. The examination found at least 5,206 people who were directly affected by a judge’s misconduct. The victims cited in disciplinary documents ranged from people who were illegally jailed to those subjected to racist, sexist and other abusive comments from judges in ways that tainted the cases.

The number is a conservative estimate. The tally doesn’t include two previously reported incidents that affected thousands of defendants and prompted sweeping reviews of judicial conduct.

“If we have a system that holds a wrongdoer accountable but we fail to address the victims, then we are really losing sight of what a justice system should be all about.”

Arthur Grim, retired judge

In Pennsylvania, the state examined the convictions of more than 3,500 teenagers sentenced by two judges. The judges were convicted of taking kickbacks as part of a scheme to fill a private juvenile detention center. In 2009, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court appointed senior judge Arthur Grim to lead a victim review, and the state later expunged criminal records for 2,251 juveniles. Grim told Reuters that every state should adopt a way to compensate victims of judicial misconduct.

“If we have a system that holds a wrongdoer accountable but we fail to address the victims, then we are really losing sight of what a justice system should be all about,” Grim said.

In another review underway in Ohio, state public defender Tim Young is scrutinizing 2,707 cases handled by a judge who retired in 2018 after being hospitalized for alcoholism. Mike Benza, a law professor at Case Western Reserve University whose students are helping identify victims, compared the work to current investigations into police abuse of power. “You see one case and then you look to see if it’s systemic,” he said.

The review, which has been limited during the coronavirus pandemic, may take a year. But Young said the time-consuming task is essential because “a fundamental injustice may have been levied against hundreds or thousands of people.”

‘Special rules for judges’

Most states afford judges accused of misconduct a gentle kind of justice. Perhaps no state better illustrates the shortcomings of America’s system for overseeing judges than Alabama.

As in most states, Alabama’s nine-member Judicial Inquiry Commission is a mix of lawyers, judges and laypeople. All are appointed. Their deliberations are secret and they operate under some of the most judge-friendly rules in the nation.

Alabama’s rules make even filing a complaint against a judge difficult. The complaint must be notarized, which means that in theory, anyone who makes misstatements about the judge can be prosecuted for perjury. Complaints about wrongdoing must be made in writing; those that arrive by phone, email or without a notary stamp are not investigated, although senders are notified why their complaints have been summarily rejected. Anonymous written complaints are shredded.

These rules can leave lawyers and litigants fearing retaliation, commission director Jenny Garrett noted in response to written questions.

“It’s a ridiculous system that protects judges and makes it easy for them to intimidate anyone with a legitimate complaint,” said Sue Bell Cobb, chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court from 2007 to 2011. In 2009, she unsuccessfully championed changes to the process and commissioned an American Bar Association report that offered a scathing review of Alabama’s rules.

In most other states, commission staff members can start investigating a judge upon receiving a phone call or email, even anonymous ones, or after learning of questionable conduct from a news report or court filing. In Alabama, staff will not begin an investigation without approval from the commission itself, which convenes about every seven weeks.

By rule, the commission also must keep a judge who is under scrutiny fully informed throughout an investigation. If a subpoena is issued, the judge receives a simultaneous copy, raising fears about witness intimidation. If a witness gives investigators a statement, the judge receives a transcript. In the U.S. justice system, such deference to individuals under investigation is extremely rare.

“It’s a ridiculous system that protects judges and makes it easy for them to intimidate anyone with a legitimate complaint.”

Sue Bell Cobb, former chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court

“Why the need for special rules for judges?” said Michael Levy, a Washington lawyer who has represented clients in high-profile criminal, corporate, congressional and securities investigations. “If judges think it’s fair and appropriate to investigate others for crimes or misconduct without providing those subjects or targets with copies of witness statements and subpoenas, why don’t judges think it’s fair to investigate judges in the same way?”

Alabama judges also are given an opportunity to resolve investigations confidentially. Reuters interviews and a review of Alabama commission records show the commission has met with judges informally at least 19 times since 2011 to offer corrective “guidance.” The identities of those judges remain confidential, as does the conduct that prompted the meetings. “Not every violation warrants discipline,” commission director Garrett said.

Since 2008, the commission has brought 21 public cases against judges, including Hayes, charging two this year.

496

Number of days Judge Hayes sentenced Marquita Johnson to jail for unpaid traffic tickets.

Two of the best-known cases brought by the commission involved Roy Moore, who was twice forced out as chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court for defying federal court orders.

Another Alabama justice fared better in challenging a misconduct complaint, however. Tom Parker, first elected to the state’s high court in 2004, pushed back when the commission investigated him in 2015 for comments he made on the radio criticizing the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision legalizing gay marriage.

Parker sued the commission in federal court, arguing the agency was infringing on his First Amendment rights. He won. Although the commission had dropped its investigation before the ruling, it was ordered to cover Parker’s legal fees: $100,000, or about a fifth of the agency’s total annual budget.

In 2018, the people of Alabama elected Parker chief justice.

These days, Parker told Reuters, Alabama judges and the agency that oversees them enjoy “a much better relationship” that’s less politically tinged. “How can I say it? It’s much more respectful between the commission and the judges now.”

“Gut instinct”

Montgomery, Alabama has a deep history of racial conflict, as reflected in the clashing concepts emblazoned on the city’s great seal: “Cradle of the Confederacy” and “Birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement.”

Jefferson Davis was inaugurated here as Confederate president after the South seceded from the Union in 1861, and his birthday is a state holiday. As was common throughout the South, the city was the site of the lynchings of Black men, crimes now commemorated at a national memorial based here. Police arrested civil rights icon Rosa Parks here in 1955 for refusing to give up her seat on a city bus to a white passenger.

Today, about 60% of Montgomery’s 198,000 residents are Black, U.S. census records show. Even so, Black motorists account for about 90% of those charged with unpaid traffic tickets, a Reuters examination of court records found. Much of Judge Hayes’ work in municipal court involved traffic cases and the collection of fines. Hayes, who is white, told Reuters that “the majority of people who come before the court are Black.”

City officials have said that neither race nor economics have played a role in police efforts to enforce outstanding warrants, no matter how minor the offense.

In April 2012, Marquita Johnson was among them. Appearing before Hayes on a Wednesday morning, the 28-year-old single mother pleaded for a break.

Johnson had struggled for eight years to pay dozens of tickets that began with a citation for failing to show proof of insurance. She had insurance, she said. But when she was pulled over, she couldn’t find the card to prove it.

Even a single ticket was a knockout blow on her minimum-wage waitress salary. In addition to fines, the court assessed a $155 fee to every ticket. Court records show that police often issued her multiple tickets for other infractions during every stop – a practice some residents call “stacking.”

Under state law, failing to pay even one ticket can result in the suspension of a driver’s license. Johnson’s decision to keep driving nonetheless – taking her children to school or to doctor visits, getting groceries, going to work – led to more tickets and deeper debt.

“I told Judge Hayes that I had lost my job and needed more time to pay,” she recounted.

By Hayes’ calculation, Johnson owed more than $12,000 in fines. He sentenced Johnson to 496 days in jail. Hayes arrived at that sentence by counting each day in jail as $25 toward the outstanding debt. A different judge later determined that Johnson actually owed half the amount calculated by Hayes, and that Hayes had incorrectly penalized her over fines she had already paid. To shave time off her sentence, Johnson washed police cars and performed other menial labor while jailed.

Hayes told Reuters that he generally found pleas of poverty hard to believe. “With my years of experience, I can tell when someone is being truthful with me,” Hayes said. He called it “gut instinct” – though he added, in a statement this week, that he also consulted “each defendant’s criminal and traffic history as well as their history of warrants and failures to appear in court.”

Of course, the law demands more of a judge than a gut call. In a 1983 landmark decision, Bearden v. Georgia, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that state judges are obligated to hold a hearing to determine whether a defendant has “willfully” chosen not to pay a fine.

According to the state’s judicial oversight commission, “Judge Hayes did not make any inquiry into Ms. Johnson’s ability to pay, whether her non-payment was willful.”

From jail, “I prayed to return to my daughters,” Johnson said. “I was sure that someone would realize that Hayes had made a mistake.”

She said her worst day in jail was her youngest daughter’s 3rd birthday. From a jail telephone, she tried to sing “Happy Birthday” but slumped to the floor in grief.

“She was choking up and crying,” said Johnson’s mother, Blanche, who was on the call. “She was devastated to be away from her children so long.”

When Johnson was freed after 10 months in jail, she learned that strangers had abused her two older children. One is now a teenager; the other is in middle school. “My kids will pay a lifetime for what the court system did to me,” Johnson said. “My daughters get frantic when I leave the house. I know they’ve had nightmares that I’m going to disappear again.”

Six months after Johnson’s release, Hayes jailed another single Black mother. Angela McCullough, then 40, had been pulled over driving home from Faulkner University, a local community college where she carried a 3.87 grade point average. As a mother of four children, including a disabled adult son, she had returned to college to pursue her dream of becoming a mental health counselor.

Police ticketed her for failing to turn on her headlights. After a background check, the officer arrested McCullough on a warrant for outstanding traffic tickets. She was later brought before Hayes.

“I can’t go to jail,” McCullough recalled pleading with the judge. “I’m a mother. I have a disabled son who needs me.”

Hayes sentenced McCullough to 100 days in jail to pay off a court debt of $1,350, court records show. Her adult son, diagnosed with schizophrenia, was held in an institution until her release.

McCullough said she cleaned jail cells in return for time off her sentence. One day, she recalled, she had to clean a blood-soaked cell where a female inmate had slit her wrists.

She was freed after 20 days, using the money she saved for tuition to pay off her tickets, she said.

Jail was the darkest chapter of her life, McCullough said, a place where “the devil was trying to take my mind.” Today, she has abandoned her pursuit of a degree. “I don’t think I’ll ever be able to afford to go back.”

A clear sign that something was amiss in Montgomery courts came in November 2013, when a federal lawsuit was filed alleging that city judges were unlawfully jailing the poor. A similar suit was filed in 2014, and two more civil rights cases were filed in 2015. Johnson and McCullough were plaintiffs.

The lawsuits detailed practices similar to those that helped fuel protests in Ferguson, Missouri, after a white police officer killed a Black teenager in 2014. In a scathing report on the origins of the unrest, the U.S. Department of Justice exposed how Ferguson had systematically used traffic enforcement to raise revenue through excessive fines, a practice that fell disproportionately hard on Black residents.

“Montgomery is just like Ferguson,” said Karen Jones, a community activist and founder of a local educational nonprofit. Jones has led recent protests in Montgomery in the wake of the killing of George Floyd, the Black man whose death under the knee of a cop in Minneapolis set off worldwide calls for racial justice.

In Montgomery, “everybody knew that the police targeted Black residents. And I sat in Hayes’ court and watched him squeeze poor people for more money, then toss them in jail where they had to work off debts with free labor to the city.”

It was years before the flurry of civil rights lawsuits against Hayes and his fellow judges had much impact on the commission. The oversight agency opened its Hayes case in summer 2015, nearly two years after plaintiffs’ lawyers in the civil rights cases filed a complaint with the body. Hayes spent another year and a half on the bench before accepting the suspension.

Under its own rules, the commission could have filed a complaint and told its staff to investigate Hayes at any time. Commission director Garrett said she is prohibited by law from explaining why the commission didn’t investigate sooner. The investigation went slowly, Garrett said, because it involved reviewing thousands of pages of court records. The commission also was busy with other cases from 2015 to early 2017, Garrett said, issuing charges against five judges, including Moore.

“Slap in the face”

A few months after Judge Hayes’ suspension ended, his term as a municipal judge was set to expire. So, the Montgomery City Council took up the question of the judge’s future on March 6, 2018. On the agenda of its meeting: whether to reappoint Hayes to another four-year term.

UNLAWFUL RULINGS: The Alabama judicial oversight agency’s determination on the wrongdoing of Judge Les Hayes.

Hayes wasn’t in the audience that night, but powerful supporters were. The city’s chief judge, Milton Westry, told the council that Hayes and his colleagues have changed how they handled cases involving indigent defendants, “since we learned a better way of doing things.” In the wake of the suits, Westry said, Hayes and his peers complied with reforms that required judges to make audio recordings of court hearings and notify lawyers when clients are jailed for failing to pay fines.

As part of a settlement in the civil case, the city judges agreed to implement changes for at least two years. Those reforms have since been abandoned, Reuters found. Both measures were deemed too expensive, Hayes and city officials confirmed.

Residents who addressed the council were incredulous that the city would consider reappointing Hayes. Jones, the community activist, reminded council members that Hayes had “pleaded guilty to violating the very laws he was sworn to uphold.”

The city council voted to rehire Hayes to a fifth consecutive term.

Marquita Johnson said she can’t understand why a judge whose unlawful rulings changed the lives of hundreds has himself emerged virtually unscathed.

“Hiring Hayes back to the bench was a slap in the face to everyone,” Johnson said. “It was a message that we don’t matter.”

On Thursday, Hayes will retire from the bench. In an earlier interview with Reuters, he declined to discuss the Johnson case. Asked whether he regrets any of the sentences he has handed out, he paused.

“I think, maybe, I could have been more sympathetic at times,” Hayes said. “Sometimes you miss a few.”

A watchdog accused, a pattern of rulings delayed, a repeat offender

Three recent cases illustrate how Alabama judges who were cited for wrongdoing were able to remain on the bench for years.

Judge Chaney: Enforced, broke rules

Court of the Judiciary finds Judge Chaney guilty of nepotism (AUDIO)

What happened when a trial judge who also served on the state’s judicial oversight board was accused of misbehavior.

Alex Chaney was just a year out of law school in 2015 when he started receiving lucrative appointments at taxpayer expense. A district judge began assigning him to represent people too poor to afford a lawyer.

That judge was his dad, Kim Chaney.

Judge Chaney is a powerful figure in rural Cullman County, where he was first elected to the bench in 1992. Chaney serves on a local bank board and has led several statewide justice associations.

In 2012, the governor honored Chaney by selecting him to also serve on Alabama’s nine-member Judicial Inquiry Commission, which investigates misconduct by judges. While on the commission, Chaney broke its ethics laws in his own courtroom.

In 2016, local attorney Tommy Drake filed a complaint against Chaney, alleging that the judge was appointing his son to represent indigent defendants, violating ethics rules that prohibit nepotism. Alex Chaney was paid $105,000 from 2015 to 2017 by the state for such court-appointed work, accounting records show.

Because Judge Chaney served on the judicial commission, Drake sent his complaint to a different state watchdog agency, the Alabama Ethics Commission. On October 4, 2017, the Ethics Commission found that Judge Chaney violated ethics rules and referred the case to the state attorney general.

The following day, records show, Judge Chaney resigned from the Judicial Inquiry Commission. But he remained a trial judge in Cullman. Eighteen months passed.

Last summer, a Reuters reporter began asking state officials about the status of the case. The officials declined to comment.

In November, Reuters sent Judge Chaney and his son queries. They did not respond. The judge’s lawyer, John Henig Jr, wrote to Reuters: “Judge Chaney is a person of remarkably good character and would never knowingly do anything unethical or wrong.”

Henig said that Judge Chaney appointed his son from a rotating list of lawyers to represent indigent defendants. Henig called the appointments “ministerial” in nature.

“If Judge Chaney’s son’s name was the next name on the list for appointments, Judge Chaney would call out his son’s name and thereafter immediately recuse himself from the case,” Henig wrote.

A Reuters review of court records showed otherwise: Judge Chaney participated in several cases after appointing his son and issued substantive decisions. For example, records show that the judge reduced bond for one of his son’s clients, and approved another’s motion to plead guilty. Henig did not respond to questions about these records.

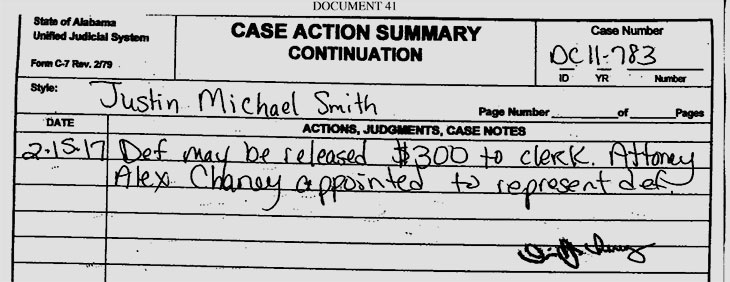

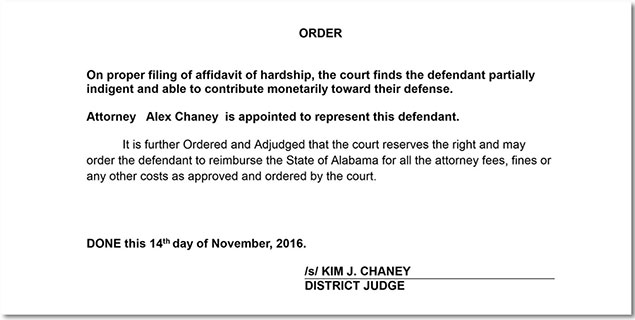

APPOINTED SON: This document shows how Judge Kim Chaney appointed his lawyer son to handle cases.

This February 7 – eight months after Reuters began inquiring about Chaney – the commission charged the judge with appointing his son to more than 200 cases and making rulings in some of them. Chaney struck a deal with the commission and retired from the bench, avoiding a trial.

During a hearing to approve the deal, commission lawyer Elizabeth Bern said Chaney should have known better than to appoint his son, especially given that he did so while a member of the oversight agency. During Chaney’s tenure, the commission had disciplined two judges who abused their office to benefit a relative.

“The nepotism provision is clear and unequivocal without exception,” she said.

Chaney did not speak during the hearing.

Drake, the lawyer who filed the complaint in 2016, said that absent the Reuters inquiries, he doubts Chaney would have retired from the bench because he is so politically powerful.

Indeed, shortly after the judge stepped down in disgrace for steering work to his son, the local bar association issued a resolution praising him.

Of Chaney, the local lawyers said, “He has always maintained the highest ethical and moral standards of the office and has been an example to all, what a judge should represent.”

Judge Kelly: “Callous indifference”

FAMILY MATTERS: Montgomery Circuit Court Judge Anita Kelly. Courtesy Montgomery Advertiser/Handout via REUTERS

How a judge left children in limbo by repeatedly failing to perform her most basic duty: ruling on cases.

Montgomery Circuit Court Judge Anita Kelly hears time-sensitive family matters such as child custody, adoption and divorce – cases in which a child remains in limbo until she rules.

Starting in 2014, court and judicial commission records show, word of years-long delays in her cases began to emerge from foster parents, lawyers, social workers and appeals court judges. Commission officials are barred by law from discussing the case, but Reuters pieced together the scope of the investigation through juvenile court records, public documents and interviews with people involved.

In May 2014, foster parents Cheri and Travis Norwood filed a complaint about Kelly with the judicial commission. They alleged the judge’s incompetence led to a traumatic, years-long delay in which a foster child who began living with the Norwoods as an infant was taken away from them at age 3 ½ and returned to live with her teenage biological mother.

“If Judge Kelly thought they should have been together, fine,” Travis Norwood said in an interview. “Why didn’t this happen sooner? Because children can’t wait. You can’t freeze a child, hold her in suspended animation until her mother is ready.”

Social workers who heard about the Norwood complaint forwarded their own concerns about Kelly’s conduct in several other cases. Nonetheless, the commission dismissed the Norwood complaint in early 2015, finding “no reasonable basis to charge the judge.”

Over the next year, more red flags emerged. State appeals court judges raised concerns about Kelly’s “continued neglect of her duty,” citing at least five cases that had untenable delays. In November 2015, a supreme court justice criticized the nearly three years it took to determine one child’s fate.

“I refuse to be another adult who has totally failed this child,” Justice Tommy Bryan wrote.

Another 20 months passed before the judicial commission took action. In August 2017, it charged Kelly with delays that “manifest a callous indifference or lack of comprehension” to children’s well-being. One child’s case, it noted, had dragged on for five years.

Kelly took her case to trial before the Court of the Judiciary, the special tribunal that weighs charges against judges. Her attorney argued that the judge worked hard and had shown no ill intent.

In 2018, the tribunal found Kelly failed to “maintain professional competence.” Kelly was suspended for 90 days. Still, she kept her job. The court said it likely would have removed Kelly from the bench if not for two factors: Voters re-elected her in 2016, and she exhibited “good character and the lack of evidence of scandal or corruption on her part.”

Her lawyer, Henry Lewis Gillis, applauded her reinstatement and said the delays never affected the quality of her decisions.

“Judge Kelly cannot change yesterday,” Gillis said. “Rather, she chooses to learn from her past experiences as she continues to handle the many, many, many cases that come before her today.”

Judge Wiggins: Give blood or go to jail

FAMILIAR FACE: Alabama Circuit Judge Marvin Wiggins. Courtesy Selma Times-Journal/Handout via REUTERS

A judge who is a repeat offender – four times over – remains on the bench.

Circuit Judge Marvin Wiggins has been hit with misconduct charges by Alabama’s judicial conduct commission four times over the past decade. In 2009, he was reprimanded and suspended for 90 days for failing to recuse himself from a voter fraud investigation involving his relatives.

“The public must be able to trust that our judges will dispense justice fairly and impartially,” the Court of the Judiciary concluded. “Judge Wiggins, by his actions, disregarded that trust.”

In 2016 – in a case that made global headlines – Wiggins was censured for offering defendants the option of giving blood instead of going to jail for failing to pay fines. A local blood drive happened to be taking place at the courthouse that day.

“If you do not have any money and you don’t want to go to jail, as an option to pay it, you can give blood today,” Wiggins told dozens of defendants, according to a recording. “Consider that as a discount rather than putting you in jail, if you do not have any money.”

Forty-one defendants gave blood that day, and the commission called Wiggins’ conduct “reprehensible and inexcusable.” Wiggins acknowledged that his comments were inappropriate, but noted he did not send anyone to jail that day for failure to pay fines.

ALERT US TO WRONGDOING

- [

Not all judges who have violated their oaths of office, broken the law or misbehaved on the bench have been brought before their states’ oversight commission. If you know of a judge who may have committed misconduct, please send us details at [email protected]. Include the name of the judge, the state, details of what the judge may have done wrong, and a way for us to contact you. Reuters investigates such tips and will contact you before publishing.

](mailto:[email protected]?Subject=Judicial misconduct)Wiggins’ lawyer, Joe Espy III, said that the judge “has always tried to cooperate” with authorities. Espy noted that Wiggins is a community leader, an ordained pastor and has been repeatedly re-elected to the bench for more than 20 years.

“He is not only a good judge but a good person,” Espy said.

Last year, Wiggins was reprimanded for directly calling the father in a custody dispute – a conversation that violated a rule prohibiting a judge from discussing a case without both sides present. A recording of the call became a key piece of evidence against Wiggins.

In preparation for trial in that case, the commission said it found a “pattern and practice” of similar one-sided calls. The commission also said it found evidence that Wiggins was meeting with divorce litigants in his chambers without lawyers present.

In November, this prompted a new commission case against Wiggins – his fourth in 10 years.

“At a very minimum,” the commission alleged, his track record indicates a “pattern of carelessness or indifferent disregard or lack of respect for the high standards imposed on the judiciary.”

But at a pretrial hearing in January, and in a subsequent order, Wiggins scored a victory before the Alabama tribunal that issues final judgment on such cases, the Court of the Judiciary. The presiding judge raised questions about whether proper procedures had been followed in the case against Wiggins.

Three weeks later, the commission dropped the case. And Wiggins returned to the bench.

This is from former Senator Tim Wirth and not easily summarized BUT worth a read.

It has got some scary scenarios in it…at election time should he lose to Biden, basically powers that T could invoke with Barr’s help, and run out the clock on counting out the electorial college with republican-lead state governments.

How Trump Could Lose the Election—And Still Remain President | Opinion

This is the story of the cursed platoon, the men who turned in Clint Lorance for his war crimes and had to watch as Trump pardoned him and made him a hero.

The Cursed Platoom

Clint Lorance had been in charge of his platoon for only three days when he ordered his men to kill three Afghans stopped on a dirt road.

A second-degree murder conviction and pardon followed.

Today, Lorance is hailed as a hero by President Trump.

His troops have suffered a very different fate.

Only a few hours had passed since President Trump pardoned 1st Lt. Clint Lorance and the men of 1st Platoon were still trying to make sense of how it was even possible.

How could a man they blamed for ruining their lives, an officer the Army convicted of second-degree murder and other charges, be forgiven so easily? How could their president allow him to just walk free?

“I feel like I’m in a nightmare,” Lucas Gray, a former specialist from the unit, texted his old squad leader, who was out of the Army and living in Fayetteville, N.C.

“I haven’t been handling it well either,” replied Mike McGuinness on Nov. 15, the day Lorance was pardoned.

“There’s literally no point in anything we did or said,” Gray continued. “Now he gets to be the hero . . .”

“And we’re left to deal with it,” McGuinness concluded.

Lorance had been in command of 1st Platoon for only three days in Afghanistan but in that short span of time had averaged a war crime a day, a military jury found. On his last day before he was dismissed, he ordered his troops to open fire on three Afghan men standing by a motorcycle on the side of the road who he said posed a threat. His actions led to a 19-year prison sentence.

He had served six years when Trump, spurred to action by relentless Fox News coverage and Lorance’s insistence that he had made a split-second decision to protect his men, set him free.

The president’s opponents described the pardon as another instance of Trump subverting the rule of law to reward allies and reap political benefits. Military officials worried that the decision to overturn a case that had already been adjudicated in the military courts sent a signal that war crimes were not worthy of severe punishment.

For the men of 1st platoon, part of the 82nd Airborne Division, the costs of the war and the fallout from the case have been profound and sometimes deadly.

Traumatized by battle, they have also been brutalized by the politicization of their service and made to feel as if the truth of what they lived in Afghanistan — already a violent and harrowing tour before Lorance assumed command — had been so demeaned that it no longer existed.

Since returning home in 2013, five of the platoon’s three dozen soldiers have died. At least four others have been hospitalized following suicide attempts or struggles with drugs or alcohol.

The last fatality came a few weeks before Lorance was pardoned when James O. Twist, 27, a Michigan state trooper and father of three, died of suicide. As the White House was preparing the official order for Trump’s signature, the men of 1st Platoon gathered in Grand Rapids, Mich., for the funeral, where they remembered Twist as a good soldier who had bravely rushed through smoke and fire to pull a friend from a bomb crater and place a tourniquet on his right leg where it had been sheared off by the blast.

They thought of the calls and texts from him that they didn’t answer because they were too busy with their own lives — and Twist, who had a caring wife, a good job and a nice house, seemed like he was doing far better than most. They didn’t know that behind closed doors he was at times verbally abusive, ashamed of his inner torment and, like so many of them, unable to articulate his pain.

By November 2019, Twist, a man the soldiers of 1st Platoon loved, was gone and Lorance was free from prison and headed for New York City, a new life and a star turn on Fox News.

This story is based on a transcript of Lorance’s 2013 court-martial at Fort Bragg, N.C., and on-the-record interviews with 15 members of 1st Platoon, as well as family members of the soldiers, including Twist’s father and wife. The soldiers also shared texts and emails they exchanged over the past several years. Twist’s family provided his journal entries from his time in the Army. Lorance declined to be interviewed.

In New York, Sean Hannity, Lorance’s biggest champion and the man most responsible for persuading Trump to pardon him, asked Lorance about the shooting and soldiers under his command.

Lorance had traded in his Army uniform for a blazer and red tie. He leaned in to the microphone. “I don’t know any of these guys. None of them know me,” Lorance said of his former troops. “To be honest with you, I can’t even remember most of their names.”

The soldiers of 1st Platoon tell their story

There’s a video at this part.

An ‘entire month of despair’

The 1st Platoon soldiers came to the Army and the war from all over the country: Maryland, California, Pennsylvania, Oregon, Indiana and Texas to name just a few. They joined for all the usual reasons: “To keep my parents off my a–,” said one soldier.

“I just needed a change,” said another.

A few had tried college but quit because they were bored or failing their classes. “I didn’t know how to handle it,” Gray said of college. “I was really immature.”

Others joined right out of high school propelled by romantic notions, inherited from veteran fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers, of service and duty. Twist’s father served in Vietnam as a clerk in an air-conditioned office before coming back to Michigan and opening a garage. In his spare time Twist Sr. was a military history buff, a passion that rubbed off on his son, who visited World War II battle sites in Europe with his dad. Twist was just 16 when he started badgering his parents to sign his enlistment papers and barely 18 when he left for basic training. His mother had died of cancer only a few months earlier.

“I got pictures of him the day we dropped him off, and he didn’t even wave goodbye,” his father recalled. “He was in pig heaven.”

Several of the 1st Platoon soldiers enlisted in search of a steady paycheck and the promise of health insurance and a middle-class life. “I needed to get out of northeast Ohio,” McGuinness said. “There wasn’t anything there.”

In 1999, he was set to pay his first union dues and go to work alongside his steelworker grandfather when the plant closed. So he became a paratrooper instead, eventually deploying three times to Afghanistan.

McGuinness didn’t look much like a paratrooper with his thick, squat body. But he liked being a soldier, jumping out of planes, firing weapons and drinking with his Army buddies. After a while the war didn’t make much sense, but he took pride in knowing that his soldiers trusted him and that he was good at his job.

Nine months before 1st Platoon landed in rural southern Afghanistan, a team of Navy SEALs killed Osama bin Laden.

Samuel Walley, the badly wounded soldier Twist pulled from the blast crater, wondered if they might be spared combat. “Wasn’t that the goal to kill bin Laden?” he recalled thinking. “Isn’t that checkmate?”

Around the same time, Twist was trying to make sense of what was to come. “I feel like the Army was a good decision, but also in my mind is a lot of dark thoughts,” he wrote in a spiral notebook. “I could die. I could come back with PTSD. I could be massively injured.”

“Maybe,” he hoped, “it will start winding down soon.”

But the decade-long war continued, driven by new, largely unattainable goals. When McGuinness saw where the platoon was headed — just 15 or so miles from the spot in southern Afghanistan where he had spent his second tour — he warned the new soldiers they were going to be “fighting against dudes who just really f—ing hate you.”

They were told by commanders they were waging a counterinsurgency war in which their top priority was winning the support of the people and protecting them from the Taliban. But no one seemed entirely sure how to accomplish that goal. They helped build a school that never opened because of a lack of teachers and willing students. They met with village elders who insisted they knew nothing about the Taliban’s operations or plans.

In May 2012, they moved to a new compound near Payenzai, a remote Afghan village west of Kandahar, which consisted of little more than mud-walled houses, hardscrabble farmers and the Taliban.

So began what Twist described, in a blog post written years later, as an “entire month of despair.”

Four soldiers were severely wounded in quick succession. On June 6, Walley lost his leg and arm to a Taliban bomb. Eight days later, yet another enemy mine wounded Mark Kerner and 1st Lt. Dominic Latino, the platoon leader. Then, on June 23, a sniper’s bullet tore through Matthew Hanes’s neck, leaving him paralyzed.

The platoon was briefly sent back to a larger base a few miles away to shower, meet with mental-health counselors and pick up their new platoon leader. Lorance had served a tour as an enlisted prison guard in Iraq before attending college and becoming an infantry officer. He had spent the first five months of his Afghanistan tour as a staff officer on a fortified base.

This was his first time in combat.

“We’re not going to lose any more men to injuries in this platoon,” he told then-Sgt. 1st Class Keith Ayres, his platoon sergeant, shortly after taking over on June 29, according to Ayres’s testimony.

His strategy, he said, was a “shock and awe” campaign designed to cow the enemy and intimidate villagers into coughing up valuable intelligence. When an Afghan farmer and his young son approached the outpost’s front gate and asked permission to move a section of razor wire a few feet so that the farmer could get into his field, Lorance threatened to have Twist and the other soldiers on guard duty kill him and his boy.

“He pointed at the child . . . at the little, tiny kid,” Twist testified. He estimated the child was 3 or 4 years old.

On Lorance’s second day, he ordered two of his sharpshooters to fire within 10 to 12 inches of unarmed villagers. His goal was to make the Afghans wonder why the Americans were shooting at them and motivate them to attend a village meeting that Lorance had scheduled for later in the week, his soldiers testified.

His real motive, though, seems to have been cruelty. “It’s funny watching those f—ers dance,” Lorance said, according to the testimony of one of his soldiers. Lorance didn’t pull the trigger. Instead, he stood by his men in the guard towers, picked the targets and issued orders. His troops finally balked when he told them to shoot near children. They refused again a few hours later when he ordered them to file a false report saying that they had taken fire from the village.

“If I don’t have the support of my NCOs then I’ll f—ing do it myself,” Lorance exclaimed, according to testimony, referring to noncommissioned officers.

On the day of the killings for which he would be convicted, Lorance posted a sign in the platoon headquarters stating that no motorcycles would be permitted in his unit’s sector. The platoon’s soldiers were falsely told before the day’s patrol that motorcycles should be considered “hostile and engaged on sight.” Several soldiers testified that Lorance told them that senior U.S. officials had ordered the change. At least two sergeants recalled the guidance had come from the Afghans and did not apply to U.S. forces. Due to the conflicting testimony, the jury of Army officers acquitted Lorance of changing the rules of engagement. Still, Lorance’s actions left soldiers confused on the critical, life-or-death question of when they were authorized to open fire.

The mission that day was a foot patrol into a nearby village to meet the elders.

Less than 30 minutes after they rolled out of the gate, three men on a motorcycle approached a cluster of Afghan National Army troops at the front of their formation. Lorance and his troops were standing about 150 to 200 yards away in an orchard, tucked behind a series of five-foot-high mud walls on which the Afghans grew grapes.

At the trial, Lorance’s soldiers recalled how he had ordered them to fire.

“Why aren’t you shooting?” he demanded.

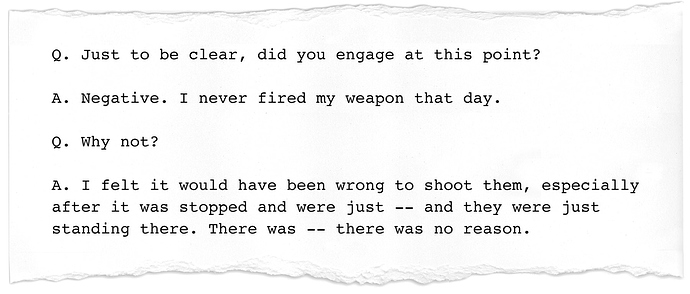

A U.S. soldier fired and missed. The motorcycle carrying the three men, none of whom appeared to be armed, came to a stop. Upon hearing the shots, McGuinness began running toward Lorance, who was closer to the front of the U.S. patrol, to see why they were shooting.

The puzzled Afghans were now standing next to the stopped motorcycle, “trying to figure out what had happened,” according to one soldier’s testimony. Gray, who was watching from a nearby armored vehicle, recognized the eldest of the three men as someone the Americans regularly met with in the village. He recalled the Afghans waving at them.

Todd Fitzgerald testifies during Clint Lorance’s 2013 court-martial at Fort Bragg, N.C.“Smoke ’em,” Lorance ordered over the radio.

At first Gray and the other soldiers in the armored vehicle weren’t sure whom Lorance wanted them to shoot. “There was a back and forth with the three of us in the vehicle,” Gray recalled in an interview.

Then Pvt. David Shilo, who was in the turret of the armored vehicle just inches from Gray, fired, striking one of the men, who fell into a drainage ditch. Because the platoon had been told that morning that motorcycles weren’t allowed in their sector, Shilo testified that he thought he was acting on a lawful order. Shilo declined to be interviewed.

The two surviving Afghan men bent to retrieve their dead colleague when Shilo cleared his weapon and shot again, killing a second Afghan. The third man ran away. Two U.S. soldiers testified that it was possible that an Afghan soldier also fired.

A few minutes later, a boy approached the dead men and the motorcycle, which was standing on the side of the road with its kickstand still down. Lorance ordered Shilo to fire a third time and disable the bike. This time he refused.

“I wasn’t going to shoot a 12-year-old boy,” Shilo testified.

David Shilo testifies during Clint Lorance’s 2013 trial at Fort Bragg, N.C.Relatives of the dead were now on the scene screaming and crying. Lorance’s immediate superior officer, Capt. Patrick Swanson, who was two miles away and couldn’t see what was happening, ordered him over the radio to search the bodies.

Lorance was convicted of lying to Swanson, telling him that villagers had carried off the corpses before his men could examine them. In fact, Lorance’s troops searched the bodies of the dead Afghans and found ID cards, scissors, some pens and three cucumbers, but no weapons, according to testimony.

The troops continued their patrol into the village while McGuinness and a small team of soldiers provided cover from a nearby roof. About 30 minutes after the first shooting, McGuinness spotted two Afghan men talking on radios.

“We have to do something to the Americans,” one of the men was saying, according to U.S. intercepts. McGuinness and his troops received permission from the company headquarters to fire and killed the two men. The platoon cut short the patrol and returned to the base.

At the outpost the soldiers were shaken. “This doesn’t feel right,” Gray said.

“It’s not f—ing right at all,” McGuinness replied.

A few minutes later Lorance burst into the platoon’s headquarters ebullient. “That was f—ing awesome,” he exclaimed, according to court testimony.

“Ayres looked sick,” one of the platoon’s soldiers testified. McGuinness was furious.

The lieutenant tried to reassure his sergeants. “I know how to report it up [so] nobody gets in trouble,” he said, according to testimony.

Lorance’s soldiers turned him in that evening, and at the July 2013 trial, 14 of his men testified under oath against him. Four of those soldiers received immunity in exchange for their testimony. Lorance did not appear on the stand, and not one of his former 1st Platoon soldiers spoke in his defense. The trial lasted three days. It took the jury of Army officers three hours to find him guilty of second-degree murder, making false statements and ordering his men to fire at Afghan civilians. The jury handed down a 20-year sentence.

In response to a Lorance clemency request, an Army general reviewed the conviction and reduced the sentence by one year.

‘Why do you care so much?’

The war crimes and their aftermath followed Lorance’s soldiers home to Fort Bragg and, in some cases, into their nightmares. On many nights Gray woke up to the image of a group of Afghan soldiers surrounding his cot and emptying their rifles into his sleeping body in retaliation for the murders.

“I dreamed it,” he said, “because I thought that’s what would happen.”

Dave Zettel wasn’t on the patrol when the killings were committed but was in the guard tower when Lorance ordered him and another soldier to fire harassing shots into the neighboring village. On his first full day back in the States, Zettel went out to a dinner with a large group from the platoon and their families.

By the end of the night, the soldiers, rattled from the tour, the stress of Lorance’s upcoming trial and the return home, were intoxicated and emotionally falling apart. Zettel held it together until he was alone in a taxi with his wife and brother. In the quiet of the cab, he felt a crushing guilt that he had made it home unscathed.

“I just lost my s—. I felt like a failure,” he said. “I felt abandoned and so f—ing angry.”

In Afghanistan, Army investigators, who were primarily pursuing Lorance, threatened Zettel with aggravated assault charges for the shootings in the tower. And they showed McGuinness a charge sheet accusing him of murder for killing the Afghans who were talking on the radios about targeting Americans.

The threats of prosecution hung over them for months. Eventually, the Army concluded that McGuinness’s actions were justified. Prosecutors never pursued charges against Zettel.

Instead the Army issued administrative letters of reprimand to Zettel and Matthew Rush, the soldier who fired the rounds at the civilians from the tower. Zettel had watched from the tower but did not shoot.

Ayres and McGuinness — the senior sergeants in the platoon — received disciplinary letters, which can hinder or delay promotions, for their failure to turn Lorance in sooner or stop the killings on the third day.

McGuinness legally changed his surname, which had been Herrmann, in an effort to shed the stigma of the crimes. “I wanted to get away from the entire situation and I thought I’ll change units and no one will know,” he said. But, because of the investigation and trial, McGuinness’s orders to report to an airborne unit in Italy were canceled. “I ended up staying. People didn’t forget,” he said. “It was awful.”

Shilo, who fired the fatal shots at the men on the motorcycle, was granted immunity and left the Army not long after the trial.

Even those who weren’t punished or even on the patrol that day felt tainted. To some of their fellow troops they were the “murder platoon,” a bunch of out-of-control soldiers who had wantonly killed Afghans. To others they were turncoats who had flipped on their commander. Gray was waiting for a parachute jump at Fort Bragg when he overheard a lieutenant colonel deride the platoon as nothing but a bunch of “traitors and cowards.” Gray was just a low-ranking specialist, so he kept his mouth shut.

The unit had seen some of the heaviest fighting of the long Afghanistan war, but received no awards for valor. There was no recognition for Twist, who had pulled Walley from a blast crater and applied a tourniquet to the remains of his arm and leg. No one acknowledged Joe Fjeldheim, the platoon medic, who had cut a hole in Hanes’s neck and inserted a breathing tube after a sniper’s bullet left him paralyzed and choking for air.

“Not a single write up. The only thing we received were Purple Hearts for the guys that got messed up,” Zettel said. “We were treated like we had an infectious disease. The Lorance issue evaporated any support from the Army when we got back, and it was absolutely crushing to those who needed help.”

A group from the unit gathered regularly at Zettel’s apartment off post to drink. Some Saturdays Fjeldheim would show up at 9:30 a.m. with booze and a plan to stay numb through the weekend. When the troops were too hung over to make it to mandatory morning formation and training, he would administer intravenous drips in the barracks.

“I was working at Macy’s, and I’d dread coming home because someone was doing something stupid or crying in the bathroom,” said Zettel’s wife, Kim. Often, it fell to her to offer a bit of empathy.

The soldiers blamed the killings when they were passed over for promotions or stripped of rank for drinking too much or missing formations. In early 2014, Gray was hospitalized for alcohol withdrawal and put on suicide watch. He had been drinking a half-gallon of whiskey each night to fall asleep. “It was my off switch,” he said. A few days into his hospital stay, when he was still dosed up on Valium, an officer visited him.

“Why are you like this?” the officer pressed. “They are just dead Afghans. Why do you care so much?”

The question infuriated Gray. Before the war crimes, he had believed he was helping Afghans and defending his country. “It’s like you’re this hardcore Christian and some entity drops from the ceiling and says it’s a sham,” he said. “That’s how it was for me. I thought of the Army as this altruistic thing. I thought it was perfect and honorable. It pains me to tell you how stupid and naive I was. The Lorance stuff just broke my faith. . . . And once you lose your values and your faith, the Army is just another job you hate.”

‘You need to stop running your mouth’

McGuinness tried to intervene on behalf of his soldiers. He talked to Gray’s new commanders, who McGuinness said wanted to run him out of the Army for being drunk.

“Did you ask him why he’s drinking too much?” McGuinness pressed them.

Zettel asked McGuinness to meet with his new platoon sergeant when the Army, without explanation, blocked him from attending Ranger School.

McGuinness also spoke up for Jarred Ruhl, who had been one of his best soldiers in combat. Ruhl came home from Afghanistan with orders for Hawaii and a promotion to sergeant. But he soon began skipping morning formation, was demoted twice to private first class and forced from the Army.

“I just don’t know how to deal with everything that happened,” Ruhl told him. He had been standing next to Lorance when the lieutenant gave the orders to kill the Afghan men.

McGuinness, who said he felt like a failure for not stopping the killings or shielding his men from the fallout, was also self-destructing. “I was mouthy and insubordinate,” he said. He felt distant from his two young children and said he was drunk “six days a week.”

When conservatives rushed to turn Lorance into a hero, McGuinness felt as though the last shreds of his integrity were under assault. Former Lt. Col. Allen West, who had been relieved of command in 2003 for staging a mock execution of an Iraqi prisoner and was later elected to Congress in the tea party wave, blasted Lorance’s conviction in a Washington Times op-ed as a product of the Army’s “appalling” rules of engagement.

The rules were drafted by generals who worried that high civilian casualty rates were driving Afghans to support the Taliban. But West insisted that the rules put U.S. troops at undue risk and reflected President Barack Obama’s “outrageous contempt for the military.” West didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Fox News’s Sean Hannity took up Lorance’s case, calling the conviction a “national disgrace.”

In 2014, McGuinness was out drinking with an Army friend, and when the friend went home, stayed at the bar until he had downed enough booze to “sedate a rhino.” A military police officer found him later that night, sitting in his truck on All American Parkway, the main drag through Fort Bragg, with a gun in his mouth.

A nurse in the psychiatric ward at Womack Army Medical Center asked him if he really wanted help. “If you tell me that to get better, I’ve got to eat a 100-pound bag of gummy bears, then I’m going to eat 100 pounds of gummy bears,” he recalled telling her. “I just can’t do this s— any more.”

It was the end of a 16-year Army career.

Soon the platoon began to suffer losses at home. First Kerner, who was wounded in a bomb blast with the unit’s first platoon leader, died in March 2015 of cancer at age 23. Doctors discovered the malignancy when they were treating his combat wounds. Five months later Hanes, who was paralyzed by the bullet he took to his neck, died of a blood clot at age 24.

“Saying I love you doesn’t even scratch the surface of how much you truly mean to me,” he wrote in a note to the platoon three months before he fell into a coma. His closest friends from the unit — Zettel, Dallas Haggard and Fjeldheim, the medic who saved his life — were at his bedside in York, Pa., during his final unconscious hours.

At the funeral there was heavy drinking, just like at Bragg, but now that many in the platoon were out of the Army and no longer had to worry about drug tests, there was also cocaine to numb the pain.

Wives traded tips about how to persuade their husbands to go to therapy and talked about hiding their guns when they grew too depressed.

Ruhl complained to McGuinness that life at home felt empty. “Are you in therapy?” asked McGuinness, who was seeing a therapist and getting ready to start college at age 33.

“I don’t know if I can do it,” Ruhl said.

“It doesn’t f—ing matter what you think you can do,” he pressed. “It can’t make things worse.”

A few months later Zettel, who had finished college and was commissioned as an officer, stopped in to see Ruhl at his home in Fort Wayne, Ind. Zettel was on his way to a leadership course for new Army officers in Missouri.

Ruhl’s stepbrother told him that Ruhl had pulled a gun on a woman in a traffic dispute just days earlier. “Take his gun,” Zettel advised Ruhl’s stepbrother. “Take it apart and hide the pieces so that he can’t get it.” It was impossible, the stepbrother said. Ruhl took his gun everywhere.

Ruhl confided to Zettel that there were days when he couldn’t stop thinking about killing himself.

“How are we going to fix this?” asked Zettel, who helped Ruhl sign up for counseling at a VA hospital.

Before he could start, Ruhl pulled his gun on an acquaintance at a party. His stepbrother tried to wrestle it away and the firearm discharged, severing Ruhl’s femoral artery. He died before paramedics arrived.

Zettel came back for the funeral, then returned to Missouri to finish his five-month leadership course. Four years had passed since the war crimes, but the murders and their aftermath still seemed inescapable. A captain teaching Zettel’s class on rules of engagement used Lorance as a case study, telling the new officers that Lorance had been trying to impose discipline on a platoon that had lost control after one of its soldiers was shot in the neck. The captain was referring to Hanes, who had given Zettel his first salute when he was commissioned as an officer.

Lorance’s soldiers, the captain continued, had violated the rules of engagement and now Lorance, who hadn’t fired a shot, was serving a 19-year prison sentence.

Zettel blew up. “I was there and you need to stop running your mouth,” he recalled shouting at the instructor.

The instructor suggested they step out of the classroom. Zettel grew angrier.

“If I ever see Lorance on the street,” he said. “I am going to rip his f—ing throat out.”

‘Y’all are being led the wrong way’

Six days after Trump was inaugurated as president, Hannity asked him in a White House interview about pardoning Lorance. “He got 30 years,” Hannity said incorrectly. “He was doing his job, protecting his team in Afghanistan.”

“We’re looking at a few of them,” said Trump of the case.

In the months after his conviction, Lorance had begun to receive support from United American Patriots (UAP), a nonprofit group that represents soldiers accused of war crimes. UAP helped Lorance find new lawyers who claimed in an appeals court filing that they had uncovered evidence showing that the younger victim was “biometrically linked” to a roadside bomb blast that occurred before his death. The sole survivor, the lawyers said, took part in attacks on U.S. forces after the Americans tried to kill him.

“The Afghan men were not civilian casualties . . . but were actually combatant bombmakers who intended to harm or kill American soldiers,” the lawyers wrote in their appeal.

In 2017, a military appeals court dismissed the biometric data as irrelevant because Lorance had “no indications that the victims posed any threat at the time of the shootings.” The judges found that the surviving victim’s decision to join the Taliban after the platoon tried to kill him probably would have helped prosecutors by demonstrating “the direct impact on U.S. forces when the local population believe they are being indiscriminately killed.”

But the biometric evidence and support from UAP helped Lorance’s mother and his legal team get on Trump’s favorite television shows — “Fox & Friends” and “Hannity” — where they offered a new account of the killings that differed dramatically from the sworn testimony. In their telling, the motorcycle wasn’t stopped on the side of the road with its kickstand down, as testimony and photos from the trial demonstrated, but was speeding toward Lorance and his men when he ordered them to fire.

“He’s got to make a split-second decision in a war zone,” Hannity said on his television show. “How did it get to the point where he got prosecuted for this?”

“I feel if he had not made that call,” Lorance’s mother replied, “my son today would be called a hero, killed in action.”

Hannity turned to Lorance’s lawyer, John Maher. “Was there anybody in the platoon that was with Clint that said that was the wrong decision?” he asked.

“That I don’t rightly know,” replied Maher, who had reviewed the platoon’s testimony.

“Then who made the determination that this was the wrong thing to do?” Hannity pressed.

“The chain of command,” Maher said.

“People that weren’t there,” Hannity concluded. Hannity and a Fox News spokeswoman did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

In a recent interview, Maher said his response to Hannity’s question had been “potentially inartful.” Lorance was in prison because the 1st Platoon soldiers turned him in and testified against him.

But Maher maintained that Lorance had made a split-second decision to protect his men from an enemy ambush. Some of the 1st Platoon soldiers said that the Afghan men had been standing on the side of the road for as long as two minutes before the U.S. gun truck opened fire on Lorance’s orders. Others, including Lorance, estimated they had been stopped for only a few seconds.

“That’s probably an eternity sitting here in the safety of this environment,” Maher said. “But I assure you that it’s not like that under volatile, uncertain, unforgiving conditions where life and death are right around the corner and a tardy decision results in death or dismemberment.”

The Afghan men were about 150 to 200 yards from the U.S. position when they were killed. To reach Lorance and his troops, they would have had to scale multiple shoulder-high mud walls.

Zach Thomas, who had been standing just yards from Lorance when he gave the order to fire, was driving to community college in 2017 when he heard Hannity talking about the Lorance case on the radio.

“My blood just started boiling,” he recalled.

Thomas had spent his last day in the Army testifying against his former platoon leader. He was just 18 when he left for Afghanistan, and like many in the unit, his return home had been difficult. He drank to blunt his PTSD and depression. Two of his sergeants were so worried about him that they let him move out of the barracks and spend his last two months living at their house. His plan after the Army was to forget about Afghanistan and start a new life in his hometown of Crosby, Tex.

Thomas pulled over on the side of the road and looked up the number for Hannity’s radio show in New York City on his cellphone.

“I’m a big fan, but y’all are being led the wrong way,” he told a producer for the show. “This isn’t some innocent guy.” The producer asked him if he knew about the biometric data Lorance’s lawyers had uncovered.

“I don’t know about any of that information, but I was there and these people were not enemy combatants,” he said. He could tell he wasn’t convincing the producer so he gave her McGuinness’s cellphone number and urged her to call him. She talked with McGuinness as well but never invited him on the show.

A handful of other soldiers from the platoon did their best to counter Lorance’s story. Todd Fitzgerald, who was also standing near Lorance when he ordered the killings, took to Reddit to defend the unit. He and several other soldiers spoke to the New York Times for a story that detailed the inaccuracies in Lorance’s defense. Fitzgerald, McGuinness and Gray were interviewed for a documentary about the case, “Leavenworth,” that aired on the Starz Network.

In April 2018, the platoon suffered its fourth death since returning home when Nick Carson, 26, crashed his car late at night.

Carson had been with McGuinness in Afghanistan on the day of the killings, and like his squad leader had been threatened with war crimes charges.

“I don’t know what’s fixing to happen, but our platoon leader is making us all out to be murderers,” he told his parents in a 2012 phone call from Afghanistan. “Just know, I am not a murderer.”

Carson’s mother and stepfather were at Fort Bragg a few months later when he returned from the war. “He got off that big plane, hugged us and cried and then he said, ‘I love y’all but I need to be by myself. I just need to go,’ ” recalled his stepfather.

Carson stayed in the Army after the combat tour, but he struggled with PTSD, depression and anger. He and Ruhl had been best friends and were supposed to go to Hawaii together when they returned from Afghanistan. After Ruhl’s death, Carson tried to explain on the platoon’s private Facebook page why he was skipping his friend’s funeral. “It’s not that I can’t physically be there,” he wrote. “I won’t let my last memory of Jarred be at his funeral. I am sorry for that. Most of you know how close Jarred and I were, so this has been extremely difficult to accept.”

On the night of the car accident that killed him, Carson had been drinking and wasn’t wearing a seat belt. His parents said he may have fallen asleep while driving. The platoon blamed the war crimes and the deployment.

In Afghanistan, the platoon had dubbed themselves the “Honey Badgers” after the fearless carnivore.

Back home, they began to refer to themselves as “the cursed platoon.”

‘Who is it this time?’

On October 23rd at 2:44 a.m., Twist’s wife, Emalyn, messaged Sgt. 1st Class Joe Morrissey, who had been Twist’s team leader with the platoon in Afghanistan.

“James committed suicide tonight,” she wrote from the hospital where the doctors were preparing to harvest his organs. “Could you let his other Army friends know. . . . This is a fucking living nightmare.” It was the platoon’s fifth death since returning home four years earlier.

Morrissey woke to the message at Fort Bragg and began sobbing. His soon-to-be ex-wife knew immediately that another member of the platoon was gone. His first call was to McGuinness, who was returning home from a late-night shift as a bouncer at a Fayetteville bar. The two immediately began calling the rest of the platoon, which was scattered across the country.

The deaths had imbued them with a grim fatalism. “Who is it this time?” a few answered when they saw the 5 a.m. calls from Morrissey’s phone.

“It’s James,” Morrissey said again and again.

At Fort Jackson, Zettel was administering a predawn fitness test to recruits when he got the call. He punched a fence and rushed back to his office so the new soldiers wouldn’t see him fall apart. Alone at his desk, Zettel thought about the steady stream of calls and texts Twist had sent him over the past five years, and he wondered if the messages were an indirect way of asking for help.

McGuinness caught Gray as he headed off to his job at a weapons arsenal in southwest Virginia. His wallpaper on his work computer was a photo of Twist and him in Afghanistan, their rifles slung across their chests. “Back when we were cool,” Twist had written when he texted it to Gray.

The hardest call was to Walley, the soldier Twist had dragged from the blast crater. “What’s wrong?” his fiancee asked him when he got the call. “It’s Twist,” Walley told her. She tried to hug him, but he pushed her away. “I need to take this in alone,” he said.

At the funeral, Walley spoke first for the platoon, rocking back and forth on his prosthetic leg. Walley was wounded a month before the murders, but they had affected him too. At times, he felt abandoned by those who had tried to distance themselves from the unit, the murders and the war. “I have to wake up every single day and look in the mirror. Every single day I am hopping in a wheelchair,” he often thought. “I don’t get to forget.”

In January 2016, he was drunk and despondent in his apartment outside Atlanta and accidentally fired his pistol through the ceiling and into the apartment above him. After the shooting, Walley cut back on his drinking and returned to college. He was just one semester from graduating.

He stared out at the packed and silent church.

“Twist would probably give me a little bit of crap right now for having not wrote a speech,” he began. “But I figured I’d just tell a story. It’s a little bit of a harsh story, but I think it needs to be told.”

Walley had spent dozens of hours reconstructing every second of the day he was injured. Eight years after the blast, he and his fellow soldiers would still argue over the smallest details: What kind of bomb had caused his wounds? Was it a pressure plate or remote-detonated? What exactly did Morrissey say as he and Carson lifted Walley into the helicopter? For Walley, the details were sacred. Remembering brought him comfort.

He took a breath and described the explosion and its aftermath. “My right leg was about 20 feet away. It was completely removed. My left leg, the tibia ripped through the [skin]; my foot was facing toward my butt,” he said. His right arm was mangled.

“Twist ended up coming through this cloudy haze,” Walley continued. “He was the most selfless man that I ever knew on this planet. He did not care if he died. He did not care if his limbs were to get ripped off. He didn’t care. He just cared that his guys were okay.”

A few minutes in a combat zone can define a life for good or for ill. “I believe that 10 minutes defined Twist,” Walley said.

Morrissey spoke next of Twist’s successes as a soldier, state trooper and father. “Those of us who knew Twist were extremely proud,” he said. “Unfortunately . . . underneath it all, the demons are still there, still tearing away at us day in and day out.”

‘The men and women in the mud and dirt’

The 1st Platoon soldiers were still filtering home from Twist’s funeral when Pete Hegseth, a “Fox & Friends” co-anchor who had advocated on Lorance’s behalf, tweeted that Lorance’s pardon was “imminent.”

The actual release came two weeks later on Nov. 15.

“It’s done. It’s a political move,” one of the 1st Platoon soldiers wrote on the group’s private Facebook page. “Time to move on.”

Ayres, who had skipped all five of the platoon’s funerals, agreed. “Not worth any of our time,” he wrote. “What matters is that everyone that matters knows he is a piece of s—. Let’s move on and enjoy life.”