In unguarded moments with senior aides, President Trump has maintained that Black Americans have mainly themselves to blame in their struggle for equality, hindered more by lack of initiative than societal impediments, according to current and former U.S. officials.

After phone calls with Jewish lawmakers, Trump has muttered that Jews “are only in it for themselves” and “stick together” in an ethnic allegiance that exceeds other loyalties, officials said.

Trump’s private musings about Hispanics match the vitriol he has displayed in public, and his antipathy to Africa is so ingrained that when first lady Melania Trump planned a 2018 trip to that continent he railed that he “could never understand why she would want to go there.”

When challenged on these views by subordinates, Trump has invariably responded with indignation. “He would say, ‘No one loves Black people more than me,’ ” a former senior White House official said. The protests rang hollow because if the president were truly guided by such sentiments he “wouldn’t need to say it,” the official said. “You let your actions speak.”

In Trump’s case, there is now a substantial record of his actions as president that have compounded the perceptions of racism created by his words.

Over 3½ years in office, he has presided over a sweeping U.S. government retreat from the front lines of civil rights, endangering decades of progress against voter suppression, housing discrimination and police misconduct.

This is the line from that article that stands out to me:

While the White House would never say so publicly, by pushing to confirm a choice before voters render their judgment on him, Mr. Trump is effectively conceding that he could lose and therefore it would be better to fill the seat immediately.

The writer clearly does not understand Trump, because he’s already openly said EXACTLY this to all effect.

Here’s the rundown of his dark qualities…as written by two psychologists.

“Get rid of the ballots” and “there won’t be a transfer,” said Donald Trump on Wednesday. This comment is a direct and dangerous expression of his anti-democratic intention. If unstopped, Trump may well destroy our 244-year-old democracy.

It is time to stop pulling punches. It is time to stop relying on political pundits to weigh in on Trump’s behavior, which they often soften and even normalize.

We are psychologists, and we are convinced Donald Trump is a psychopath. His malignant behavior over the past four years is growing and escalating right before our eyes. Trump’s psychopathy will change us forever if he is not stopped.

This is not hyperbole. This is not an expression of "a left-wing agenda.” This is a mental health opinion based on thousands of hours of documented behavior by this president.

He breaks norms, rules, and laws with impunity.

He lies, on average, 15 times a day.

He peddles fake conspiracy theories and irrational magical thinking.

He has been accused of sexually predatory behavior by at least 25 women.

He blames, scapegoats and gaslights as easily as he breathes.

He undermines the vital role of the free press because he abhors oversight and accountability.

His lies and anti-scientific advice and intentional downplaying of the coronavirus pandemic has led to countless American deaths.

He is callous and cold and unfeeling because he has no conscience.

He denigrates and humiliates anyone and everyone in his path.

He has no respect for military heroes or renowned experts.

He is racist and xenophobic.

He incites violence and culture wars.

He is obsessed with power and adoration.

He is a greedy opportunist.

He is corrupt to the core.

Now Trump is desperate to win re-election. He does not want to lose his hold on power for a number of reasons, most notably his insatiable thirst for attention. He is afraid of facing criminal charges once he leaves office. He is already essentially an unindicted co-conspirator in a campaign finance crime. He knows he is lawless and corrupt; that is why he lies about it so frequently and fervently.

Trump will do absolutely anything — no matter how untruthful or illegal or immoral — to win this election. He has already compromised the Postal Service.

Trump will declare victory as soon as he can, even if millions of ballots have not been counted. If need be, he will challenge the election results so that the Supreme Court will ultimately choose him for a second term. In fact, he has openly admitted that he wants to immediately replace Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg because of the upcoming election. Trump’s desire to sabotage our election process is the behavior of a dictator.

Trump is letting the Russians intervene on his behalf in this election. They are doing so. Before Trump, such an invitation would have been considered treasonous and criminal.

Trump is fearmongering about Joe Biden and all Democrats on a daily basis. His allegations against Biden are outrageous and even bizarre; Trump asserted that there are “people in dark shadows” who are controlling Biden.

Trump’s falsehoods about health insurance and pre-existing illnesses and Social Security benefits and Medicare are intended to sow doubt and confusion in the American public. He says one thing but does the exact opposite. He tells us that he will protect pre-existing illnesses, but behind the scenes he is taking court action to disallow them.

Trump is the most psychiatrically disordered president in history.

Donald Trump is dishonest and destructive and evil. He has become embolden and empowered by the complicity of his Republican sycophants. Sadly, he now believes he is destined to carry on his mission. He feels unstoppable. And he must be stopped before it is too late.

Blotcky is a clinical psychologist in Birmingham, Ala. Norrholm, also a psychologist, is on faculty at the Wayne State University School of Medicine in Detroit.

The Interregnum comprises 79 days, carefully bounded by law. Among them are “the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December,” this year December 14, when the electors meet in all 50 states and the District of Columbia to cast their ballots for president; “the 3d day of January,” when the newly elected Congress is seated; and “the sixth day of January,” when the House and Senate meet jointly for a formal count of the electoral vote. In most modern elections these have been pro forma milestones, irrelevant to the outcome. This year, they may not be.

…

The interregnum allots 35 days for the count and its attendant lawsuits to be resolved. On the 36th day, December 8, an important deadline arrives.At this stage, the actual tabulation of the vote becomes less salient to the outcome. That sounds as though it can’t be right, but it is: The combatants, especially Trump, will now shift their attention to the appointment of presidential electors.

December 8 is known as the “safe harbor” deadline for appointing the 538 men and women who make up the Electoral College. The electors do not meet until six days later, December 14, but each state must appoint them by the safe-harbor date to guarantee that Congress will accept their credentials. The controlling statute says that if “any controversy or contest” remains after that, then Congress will decide which electors, if any, may cast the state’s ballots for president.

Shortly after the pandemic broke out in the United States, in March, Elias, in a blog post titled “Four Pillars to Safeguard Vote by Mail,” outlined the Democrats’ approach:

Postage must be free or prepaid by the government

Ballots postmarked on or before Election Day must count.

Signature matching laws need to be reformed to protect voters.

Community organizations should be permitted to help collect and deliver voted, sealed ballots.

David Rivkin, who served in the White House counsel’s office and Justice Department under Presidents Reagan and George H.W. Bush, warned about what he characterized as the “Titanic scenario”:

- Disputed election results in many states with potentially inconsistent opinions on the same legal issues.

- A deadlocked Supreme Court if Trump doesn’t fill Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s seat before the election.

- It becomes up to the House of Representatives to declare the winner. But the question of who controls the delegations in the House may also be at play, given that every member of Congress is also up for reelection this year.

More scathing portrayals of the President showing him as manipulative, underhanded and mean when it came to his father’s (Fred Sr) decline into dementia and T’s wanton money grubbing behavior when it came to redoing his father’s will.

It comes to light mostly due to Mary Trump’s book, but as we get closer to the election, there will be scads of this kind of information, since T has hidden all of his taxes from anyone. Seems

like an appropriate money trail to search out what T is really like (which we unfortunately knew from the start)

It was a fragile moment for the senior Trump, who was 85 years old and had built a real estate empire worth hundreds of millions of dollars. He would soon be diagnosed with cognitive problems, such as being unable to recall things he was told 30 minutes earlier or remember his birth date, according to his medical records, which were included in a related court case.

Now, those records and other sources of information about the episode obtained by The Washington Post reveal the extent of Fred Trump Sr.’s cognitive impairment and how Donald’s effort to change his father’s will tore apart the Trump family, which continues to reverberate today.

The recent release of a tell-all book by the president’s niece Mary L. Trump and the disclosure of secret recordings of her conversations with her aunt reflect the ongoing resentment of some family members toward Donald Trump’s attempt to change his father’s will.

With the election weeks away, the documents and recordings provide more fodder for Mary Trump’s continuing efforts to see her uncle defeated by Democrat Joe Biden, whom she has said she would do “everything in my power” to elect.

Trump’s sister Maryanne Trump Barry was recorded by her niece in January 2019 expressing outrage over her brother’s efforts to change the will as their father’s mental capacity was declining. “Dad was in dementia,” Barry said.

Barry said that when she was asked by her father in 1990 to review the proposed changes, she consulted with her husband, John Barry, an attorney familiar with estate law who died in 2000. “I show it to John, and he says, ‘Holy s–t.’ It was basically taking the whole estate and giving it to Donald,” Barry said.

Barry helped convince her father to reject her brother’s effort. As a result, Donald Trump “didn’t talk to me for two years,” Barry said during one of several conversations her niece recorded. Mary Trump recently provided the tapes to The Post.

…

Mary Trump said in a statement to The Post that Donald Trump’s initial effort to change his father’s will when his mental state was in decline is still relevant today because it shows how he put his own interests above even those of his own family members.

“As demonstrated by his willingness to alter his father’s will illicitly and in secret, there are no limits to Donald’s unethical behavior,” she said. “Because doing so benefited Donald, however, he had no compunction about deceiving his father in order to defraud his own siblings. There is no code of conduct, no moral or ethical imperative that stands in the way of Donald’s craven willingness to achieve his ends no matter the means.”

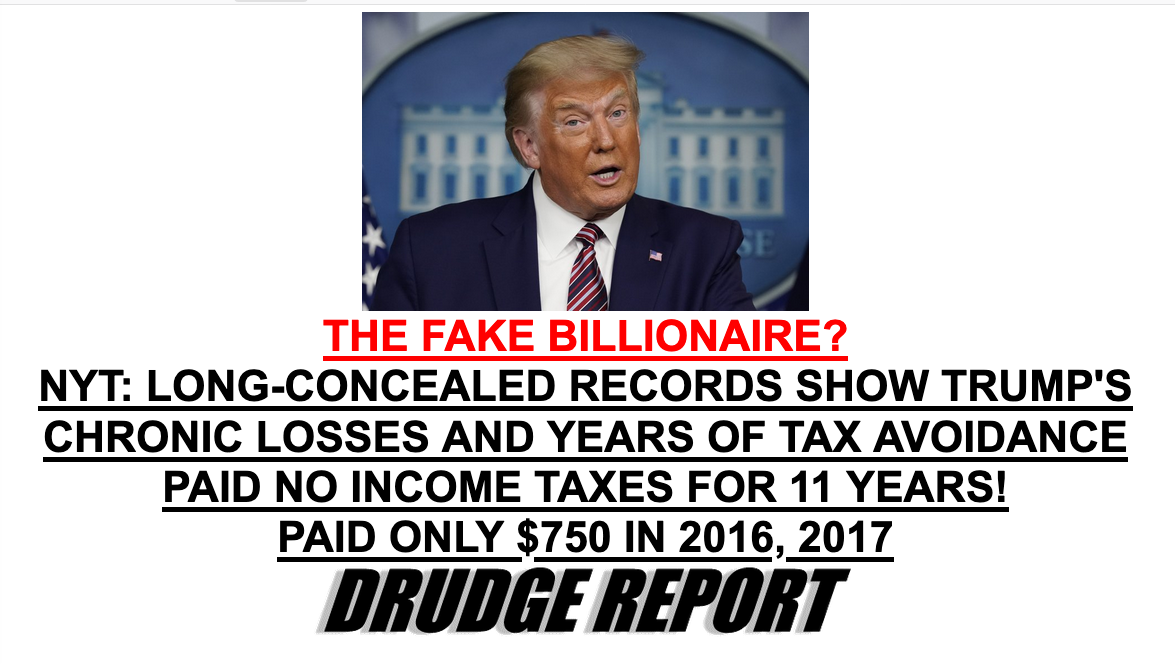

Where did these tax returns come from you wonder? But here they are… And how was he entitled to a $72.9 Million tax refund after declaring losses? Lots here to look through.

The Times obtained Donald Trump’s tax information extending over more than two decades, revealing struggling properties, vast write-offs, an audit battle and hundreds of millions in debt coming due.Donald J. Trump paid $750 in federal income taxes the year he won the presidency. In his first year in the White House, he paid another $750.

He had paid no income taxes at all in 10 of the previous 15 years — largely because he reported losing much more money than he made.

As the president wages a re-election campaign that polls say he is in danger of losing, his finances are under stress, beset by losses and hundreds of millions of dollars in debt coming due that he has personally guaranteed. Also hanging over him is a decade-long audit battle with the Internal Revenue Service over the legitimacy of a $72.9 million tax refund that he claimed, and received, after declaring huge losses. An adverse ruling could cost him more than $100 million.

The tax returns that Mr. Trump has long fought to keep private tell a story fundamentally different from the one he has sold to the American public. His reports to the I.R.S. portray a businessman who takes in hundreds of millions of dollars a year yet racks up chronic losses that he aggressively employs to avoid paying taxes. Now, with his financial challenges mounting, the records show that he depends more and more on making money from businesses that put him in potential and often direct conflict of interest with his job as president.

The New York Times has obtained tax-return data extending over more than two decades for Mr. Trump and the hundreds of companies that make up his business organization, including detailed information from his first two years in office. It does not include his personal returns for 2018 or 2019. This article offers an overview of The Times’s findings; additional articles will be published in the coming weeks.

The returns are some of the most sought-after, and speculated-about, records in recent memory. In Mr. Trump’s nearly four years in office — and across his endlessly hyped decades in the public eye — journalists, prosecutors, opposition politicians and conspiracists have, with limited success, sought to excavate the enigmas of his finances. By their very nature, the filings will leave many questions unanswered, many questioners unfulfilled. They comprise information that Mr. Trump has disclosed to the I.R.S., not the findings of an independent financial examination. They report that Mr. Trump owns hundreds of millions of dollars in valuable assets, but they do not reveal his true wealth. Nor do they reveal any previously unreported connections to Russia.

…

The tax data examined by The Times provides a road map of revelations, from write-offs for the cost of a criminal defense lawyer and a mansion used as a family retreat to a full accounting of the millions of dollars the president received from the 2013 Miss Universe pageant in Moscow.

Together with related financial documents and legal filings, the records offer the most detailed look yet inside the president’s business empire. They reveal the hollowness, but also the wizardry, behind the self-made-billionaire image — honed through his star turn on “The Apprentice” — that helped propel him to the White House and that still undergirds the loyalty of many in his base.

Ultimately, Mr. Trump has been more successful playing a business mogul than being one in real life.

Adding this 18 Takeaways

The New York Times has obtained tax-return data for President Trump and his companies that covers more than two decades. Mr. Trump has long refused to release this information, making him the first president in decades to hide basic details about his finances. His refusal has made his tax returns among the most sought-after documents in recent memory.

Among the key findings of The Times’s investigation:

- Mr. Trump paid no federal income taxes in 11 of 18 years that The Times examined. In 2017, after he became president, his tax bill was only $750.

- He has reduced his tax bill with questionable measures, including a $72.9 million tax refund that is the subject of an audit by the Internal Revenue Service.

- Many of his signature businesses, including his golf courses, report losing large amounts of money — losses that have helped him to lower his taxes.

- The financial pressure on him is increasing as hundreds of millions of dollars in loans he personally guaranteed are soon coming due.

- Even while declaring losses, he has managed to enjoy a lavish lifestyle by taking tax deductions on what most people would consider personal expenses, including residences, aircraft and $70,000 in hairstyling for television.

- Ivanka Trump, while working as an employee of the Trump Organization, appears to have received “consulting fees” that also helped reduce the family’s tax bill.

- As president, he has received more money from foreign sources and U.S. interest groups than previously known. The records do not reveal any previously unreported connections to Russia.

It is important to remember that the returns are not an unvarnished look at Mr. Trump’s business activity. They are instead his own portrayal of his companies, compiled for the I.R.S. But they do offer the most detailed picture yet available.

Below is a deeper look at the takeaways. The main article based on the investigation contains much more information, as does a timeline of the president’s finances. Dean Baquet, the executive editor, has written a note explaining why The Times is publishing these findings.

The president’s tax avoidance

Mr. Trump has paid no federal income taxes for much of the past two decades.

In addition to the 11 years in which he paid no taxes during the 18 years examined by The Times, he paid only $750 in each of the two most recent years — 2016 and 2017.

He has managed to avoid taxes while enjoying the lifestyle of a billionaire — which he claims to be — while his companies cover the costs of what many would consider personal expenses.

This tax avoidance sets him apart from most other affluent Americans.

Taxes on wealthy Americans have declined sharply over the past few decades, and many use loopholes to reduce their taxes below the statutory rates. But most affluent people still pay a lot of federal income tax.

In 2017, the average federal income rate for the highest-earning .001 percent of tax filers — that is, the most affluent 1/100,000th slice of the population — was 24.1 percent, according to the I.R.S.

Over the past two decades, Mr. Trump has paid about $400 million less in combined federal income taxes than a very wealthy person who paid the average for that group each year.

His tax avoidance also sets him apart from past presidents.

Mr. Trump may be the wealthiest U.S. president in history. Yet he has often paid less in taxes than other recent presidents. Barack Obama and George W. Bush each regularly paid more than $100,000 a year — and sometimes much more — in federal income taxes while in office.

Mr. Trump, by contrast, is running a federal government to which he has contributed almost no income tax revenue in many years.

A large refund has been crucial to his tax avoidance.

Mr. Trump did face large tax bills after the initial success of “The Apprentice” television show, but he erased most of these tax payments through a refund. Combined, Mr. Trump initially paid almost $95 million in federal income taxes over the 18 years. He later managed to recoup most of that money, with interest, by applying for and receiving a $72.9 million tax refund, starting in 2010.

The refund reduced his total federal income tax bill between 2000 and 2017 to an annual average of $1.4 million. By comparison, the average American in the top .001 percent of earners paid about $25 million in federal income taxes each year over the same span.

The $72.9 million refund has since become the subject of a long-running battle with the I.R.S.

When applying for the refund, he cited a giant financial loss that may be related to the failure of his Atlantic City casinos. Publicly, he also claimed that he had fully surrendered his stake in the casinos.

But the real story may be different from the one he told. Federal law holds that investors can claim a total loss on an investment, as Mr. Trump did, only if they receive nothing in return. Mr. Trump did appear to receive something in return: 5 percent of the new casino company that formed when he renounced his stake.

In 2011, the I.R.S. began an audit reviewing the legitimacy of the refund. Almost a decade later, the case remains unresolved, for unknown reasons, and could ultimately end up in federal court, where it could become a matter of public record.

Business expenses and personal benefits

Mr. Trump classifies much of the spending on his personal lifestyle as the cost of business.

His residences are part of the family business, as are the golf courses where he spends so much time. He has classified the cost of his aircraft, used to shuttle him among his homes, as a business expense as well. Haircuts — including more than $70,000 to style his hair during “The Apprentice” — have fallen into the same category. So did almost $100,000 paid to a favorite hair and makeup artist of Ivanka Trump.

All of this helps to reduce Mr. Trump’s tax bill further, because companies can write off business expenses.

Seven Springs, his estate in Westchester County, N.Y., typifies his aggressive definition of business expenses.

Mr. Trump bought the estate, which stretches over more than 200 acres in Bedford, N.Y., in 1996. His sons Eric and Donald Jr. spent summers living there when they were younger. “This is really our compound,” Eric told Forbes in 2014. “Today,” the Trump Organization website continues to report, “Seven Springs is used as a retreat for the Trump family.”

Nonetheless, the elder Mr. Trump has classified the estate as an investment property, distinct from a personal residence. As a result, he has been able to write off $2.2 million in property taxes since 2014 — even as his 2017 tax law has limited individuals to writing off only $10,000 in property taxes a year.

The ‘consulting fees’

Across nearly all of his projects, Mr. Trump’s companies set aside about 20 percent of income for unexplained ‘consulting fees.’

These fees reduce taxes, because companies are able to write them off as a business expense, lowering the amount of final profit subject to tax.

Mr. Trump collected $5 million on a hotel deal in Azerbaijan, for example, and reported $1.1 million in consulting fees. In Dubai, there was a $630,000 fee on $3 million in income. Since 2010, Mr. Trump has written off some $26 million in such fees.

His daughter appears to have received some of these consulting fees, despite having been a top Trump Organization executive.

The Times investigation discovered a striking match: Mr. Trump’s private records show that his company once paid $747,622 in fees to an unnamed consultant for hotel projects in Hawaii and Vancouver, British Columbia. Ivanka Trump’s public disclosure forms — which she filed when joining the White House staff in 2017 — show that she had received an identical amount through a consulting company she co-owned.

Money-losing businesses

Many of the highest-profile Trump businesses lose large amounts of money.

Since 2000, he has reported losing more than $315 million at the golf courses that he often describes as the heart of his empire. Much of this has been at Trump National Doral, a resort near Miami that he bought in 2012. And his Washington hotel, opened in 2016, has lost more than $55 million.

An exception: Trump Tower in New York, which reliably earns him more than $20 million in profits a year.

The most successful part of the Trump business has been his personal brand.

The Times calculates that between 2004 and 2018, Mr. Trump made a combined $427.4 million from selling his image — an image of unapologetic wealth through shrewd business management. The marketing of this image has been a huge success, even if the underlying management of many of the operating Trump companies has not been.

Other firms, especially in real estate, have paid for the right to use the Trump name. The brand made possible the “The Apprentice” — and the show then took the image to another level.

Of course, Mr. Trump’s brand also made possible his election as the first United States president with no prior government experience.

But his unprofitable companies still served a financial purpose: reducing his tax bill.

The Trump Organization — a collection of more than 500 entities, virtually all of them wholly owned by Mr. Trump — has used the losses to offset the rich profits from the licensing of the Trump brand and other profitable pieces of its business.

The reported losses from the operating businesses were so large that they often fully erased the licensing income, leaving the organization to claim that it earns no money and thus owes no taxes. This pattern is an old one for Mr. Trump. The collapse of major parts of his business in the early 1990s generated huge losses that he used to reduce his taxes for years afterward.

Large bills looming

With the cash from ‘The Apprentice,’ Mr. Trump went on his biggest buying spree since the 1980s.

“The Apprentice,” which debuted on NBC in 2004, was a huge hit. Mr. Trump received 50 percent of its profits, and he went on to buy more than 10 golf courses and multiple other properties. The losses at these properties reduced his tax bill.

But the strategy ran into trouble as the money from “The Apprentice” began to decline. By 2015, his financial condition was worsening.

His 2016 presidential campaign may have been partly an attempt to resuscitate his brand.

The financial records do not answer this question definitively. But the timing is consistent: Mr. Trump announced a campaign that seemed a long shot to win, but was almost certain to bring him newfound attention, at the same time that his businesses were in need of a new approach.

The presidency has helped his business.

Since he became a leading presidential candidate, he has received large amounts of money from lobbyists, politicians and foreign officials who pay to stay at his properties or join his clubs. The Times investigation puts precise numbers on this spending for the first time.

A surge of new members at the Mar-a-Lago club in Florida gave him an additional $5 million a year from the business since 2015. The roofing materials manufacturer GAF spent at least $1.5 million at Doral in 2018 as its industry was seeking changes in federal regulations. The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association paid at least $397,602 in 2017 to the Washington hotel, where it held at least one event during its World Summit in Defense of Persecuted Christians.

In his first two years in the White House, Mr. Trump received millions of dollars from projects in foreign countries, including $3 million from the Philippines, $2.3 million from India and $1 million from Turkey.

But the presidency has not resolved his core financial problem: Many of his businesses continue to lose money.

With “The Apprentice” revenue declining, Mr. Trump has absorbed the losses partly through one-time financial moves that may not be available to him again.

In 2012, he took out a $100 million mortgage on the commercial space in Trump Tower. He has also sold hundreds of millions worth of stock and bonds. But his financial records indicate that he may have as little as $873,000 left to sell.

He will soon face several major bills that could put further pressure on his finances.

He appears to have paid off none of the principal of the Trump Tower mortgage, and the full $100 million comes due in 2022. And if he loses his dispute with the I.R.S. over the 2010 refund, he could owe the government more than $100 million (including interest on the original amount).

He is personally on the hook for some of these bills.

In the 1990s, Mr. Trump nearly ruined himself by personally guaranteeing hundreds of millions of dollars in loans, and he has since said that he regretted doing so. But he has taken the same step again, his tax records show. He appears to be responsible for loans totaling $421 million, most of which is coming due within four years.

Should he win re-election, his lenders could be placed in the unprecedented position of weighing whether to foreclose on a sitting president. Whether he wins or loses, he will probably need to find new ways to use his brand — and his popularity among tens of millions of Americans — to make money.

Adding - letter from the editor

An Editor’s Note on the Trump Tax Investigation

The New York Times has examined decades of President Trump’s financial records, assembling the most comprehensive picture yet of his business dealings.

By Dean Baquet

- Sept. 27, 2020Updated 5:32 p.m. ET

Today we are publishing the results of an examination of decades of personal and corporate tax records for President Trump and his businesses in the United States and abroad. The records stretch from his days as a high-profile New York real estate investor through the beginning of his time in the White House.

A team of New York Times reporters has pored over this information to assemble the most comprehensive picture of the president’s finances and business dealings to date, and we will continue our reporting and publish additional articles about our findings in the weeks ahead. We are not making the records themselves public because we do not want to jeopardize our sources, who have taken enormous personal risks to help inform the public.

We are publishing this report because we believe citizens should understand as much as possible about their leaders and representatives — their priorities, their experiences and also their finances. Every president since the mid-1970s has made his tax information public. The tradition ensures that an official with the power to shake markets and change policy does not seek to benefit financially from his actions.

Mr. Trump, one of the wealthiest presidents in the nation’s history, has broken with that practice. As a candidate and as president, Mr. Trump has said he wanted to make his tax returns public, but he has never done so. In fact, he has fought relentlessly to hide them from public view and has falsely asserted that he could not release them because he was being audited by the Internal Revenue Service. More recently, Mr. Trump and the Justice Department have fought subpoenas from congressional and New York State investigators seeking his taxes and other financial records.

Our latest findings build on our previous reporting about the president’s finances. The records show a significant gap between what Mr. Trump has said to the public and what he has disclosed to federal tax authorities over many years. They also underscore why citizens would want to know about their president’s finances: Mr. Trump’s businesses appear to have benefited from his position, and his far-flung holdings have created potential conflicts between his own financial interests and the nation’s diplomatic interests.

The reporters who examined these records have been covering the president’s finances and taxes for almost four years. Their work on this and other projects was guided by Paul Fishleder, a senior investigative editor, and Matthew Purdy, a deputy managing editor who oversees investigations and special projects at The Times.

Some will raise questions about publishing the president’s personal tax information. But the Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled that the First Amendment allows the press to publish newsworthy information that was legally obtained by reporters even when those in power fight to keep it hidden. That powerful principle of the First Amendment applies here.

Re-posting this over here:

They have his taxes… and it’s huge. It shows a constant pattern of abuse, millions in losses, and that he only paid $750 his first two years as president and NOTHING for 10 of the last 15 years.

https://twitter.com/i/events/1310332632098463744

Long-Concealed Records Show Trump’s Chronic Losses and Years of Tax Avoidance

The Times obtained Donald Trump’s tax information extending over more than two decades, revealing struggling properties, vast write-offs, an audit battle and hundreds of millions in debt coming due.

Donald J. Trump paid $750 in federal income taxes the year he won the presidency. In his first year in the White House, he paid another $750.

He had paid no income taxes at all in 10 of the previous 15 years — largely because he reported losing much more money than he made.

As the president wages a re-election campaign that polls say he is in danger of losing, his finances are under stress, beset by losses and hundreds of millions of dollars in debt coming due that he has personally guaranteed. Also hanging over him is a decade-long audit battle with the Internal Revenue Service over the legitimacy of a $72.9 million tax refund that he claimed, and received, after declaring huge losses. An adverse ruling could cost him more than $100 million.

The tax returns that Mr. Trump has long fought to keep private tell a story fundamentally different from the one he has sold to the American public. His reports to the I.R.S. portray a businessman who takes in hundreds of millions of dollars a year yet racks up chronic losses that he aggressively employs to avoid paying taxes. Now, with his financial challenges mounting, the records show that he depends more and more on making money from businesses that put him in potential and often direct conflict of interest with his job as president.

The New York Times has obtained tax-return data extending over more than two decades for Mr. Trump and the hundreds of companies that make up his business organization, including detailed information from his first two years in office. It does not include his personal returns for 2018 or 2019. This article offers an overview of The Times’s findings; additional articles will be published in the coming weeks.

The returns are some of the most sought-after, and speculated-about, records in recent memory. In Mr. Trump’s nearly four years in office — and across his endlessly hyped decades in the public eye — journalists, prosecutors, opposition politicians and conspiracists have, with limited success, sought to excavate the enigmas of his finances. By their very nature, the filings will leave many questions unanswered, many questioners unfulfilled. They comprise information that Mr. Trump has disclosed to the I.R.S., not the findings of an independent financial examination. They report that Mr. Trump owns hundreds of millions of dollars in valuable assets, but they do not reveal his true wealth. Nor do they reveal any previously unreported connections to Russia.

In response to a letter summarizing The Times’s findings, Alan Garten, a lawyer for the Trump Organization, said that “most, if not all, of the facts appear to be inaccurate” and requested the documents on which they were based. After The Times declined to provide the records, in order to protect its sources, Mr. Garten took direct issue only with the amount of taxes Mr. Trump had paid.

“Over the past decade, President Trump has paid tens of millions of dollars in personal taxes to the federal government, including paying millions in personal taxes since announcing his candidacy in 2015,” Mr. Garten said in a statement.

With the term “personal taxes,” however, Mr. Garten appears to be conflating income taxes with other federal taxes Mr. Trump has paid — Social Security, Medicare and taxes for his household employees. Mr. Garten also asserted that some of what the president owed was “paid with tax credits,” a misleading characterization of credits, which reduce a business owner’s income-tax bill as a reward for various activities, like historic preservation.

The tax data examined by The Times provides a road map of revelations, from write-offs for the cost of a criminal defense lawyer and a mansion used as a family retreat to a full accounting of the millions of dollars the president received from the 2013 Miss Universe pageant in Moscow.

Together with related financial documents and legal filings, the records offer the most detailed look yet inside the president’s business empire. They reveal the hollowness, but also the wizardry, behind the self-made-billionaire image — honed through his star turn on “The Apprentice” — that helped propel him to the White House and that still undergirds the loyalty of many in his base.

Ultimately, Mr. Trump has been more successful playing a business mogul than being one in real life.

“The Apprentice,” along with the licensing and endorsement deals that flowed from his expanding celebrity, brought Mr. Trump a total of $427.4 million, The Times’s analysis of the records found. He invested much of that in a collection of businesses, mostly golf courses, that in the years since have steadily devoured cash — much as the money he secretly received from his father financed a spree of quixotic overspending that led to his collapse in the early 1990s.

Indeed, his financial condition when he announced his run for president in 2015 lends some credence to the notion that his long-shot campaign was at least in part a gambit to reanimate the marketability of his name.

As the legal and political battles over access to his tax returns have intensified, Mr. Trump has often wondered aloud why anyone would even want to see them. “There’s nothing to learn from them,” he told The Associated Press in 2016. There is far more useful information, he has said, in the annual financial disclosures required of him as president — which he has pointed to as evidence of his mastery of a flourishing, and immensely profitable, business universe.

In fact, those public filings offer a distorted picture of his financial state, since they simply report revenue, not profit. In 2018, for example, Mr. Trump announced in his disclosure that he had made at least $434.9 million. The tax records deliver a very different portrait of his bottom line: $47.4 million in losses.

Tax records do not have the specificity to evaluate the legitimacy of every business expense Mr. Trump claims to reduce his taxable income — for instance, without any explanation in his returns, the general and administrative expenses at his Bedminster golf club in New Jersey increased fivefold from 2016 to 2017. And he has previously bragged that his ability to get by without paying taxes “makes me smart,” as he said in 2016. But the returns, by his own account, undercut his claims of financial acumen, showing that he is simply pouring more money into many businesses than he is taking out.

The picture that perhaps emerges most starkly from the mountain of figures and tax schedules prepared by Mr. Trump’s accountants is of a businessman-president in a tightening financial vise.

Most of Mr. Trump’s core enterprises — from his constellation of golf courses to his conservative-magnet hotel in Washington — report losing millions, if not tens of millions, of dollars year after year.

His revenue from “The Apprentice” and from licensing deals is drying up, and several years ago he sold nearly all the stocks that now might have helped him plug holes in his struggling properties.

The tax audit looms.

And within the next four years, more than $300 million in loans — obligations for which he is personally responsible — will come due.

Against that backdrop, the records go much further toward revealing the actual and potential conflicts of interest created by Mr. Trump’s refusal to divest himself of his business interests while in the White House. His properties have become bazaars for collecting money directly from lobbyists, foreign officials and others seeking face time, access or favor; the records for the first time put precise dollar figures on those transactions.

At the Mar-a-Lago club in Palm Beach, Fla., a flood of new members starting in 2015 allowed him to pocket an additional $5 million a year from the business. At his Doral golf resort near Miami, the roofing materials manufacturer GAF spent at least $1.5 million in 2018 even as its industry was lobbying the Trump administration to roll back “egregious” federal regulations. In 2017, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association paid at least $397,602 to the Washington hotel, where the group held at least one event during its four-day World Summit in Defense of Persecuted Christians.

The Times was also able to take the fullest measure to date of the president’s income from overseas, where he holds ultimate sway over American diplomacy. When he took office, Mr. Trump said he would pursue no new foreign deals as president. Even so, in his first two years in the White House, his revenue from abroad totaled $73 million. And while much of that money was from his golf properties in Scotland and Ireland, some came from licensing deals in countries with authoritarian-leaning leaders or thorny geopolitics — for example, $3 million from the Philippines, $2.3 million from India and $1 million from Turkey.

He reported paying taxes, in turn, on a number of his overseas ventures. In 2017, the president’s $750 contribution to the operations of the U.S. government was dwarfed by the $15,598 he or his companies paid in Panama, the $145,400 in India and the $156,824 in the Philippines.

Mr. Trump’s U.S. payment, after factoring in his losses, was roughly equivalent, in dollars not adjusted for inflation, to another presidential tax bill revealed nearly a half-century before. In 1973, The Providence Journal reported that, after a charitable deduction for donating his presidential papers, Richard M. Nixon had paid $792.81 in 1970 on income of about $200,000.

The leak of Mr. Nixon’s small tax payment caused a precedent-setting uproar: Henceforth, presidents, and presidential candidates, would make their tax returns available for the American people to see.

“I would love to do that,” Mr. Trump said in 2014 when asked whether he would release his taxes if he ran for president. He’s been backpedaling ever since.

When he ran, he said he might make his taxes public if Hillary Clinton did the same with the deleted emails from her private server — an echo of his taunt, while stoking the birther fiction, that he might release the returns if President Barack Obama released his birth certificate. He once boasted that his tax returns were “very big” and “beautiful.” But making them public? “It’s very complicated.” He often claims that he cannot do so while under audit — an argument refuted by his own I.R.S. commissioner. When prosecutors and congressional investigators issued subpoenas for his returns, he wielded not just his private lawyers but also the power of his Justice Department to stalemate them all the way to the Supreme Court.

Mr. Trump’s elaborate dance and defiance have only stoked suspicion about what secrets might lie hidden in his taxes. Is there a financial clue to his deference to Russia and its president, Vladimir V. Putin? Did he write off as a business expense the hush-money payment to the pornographic film star Stormy Daniels in the days before the 2016 election? Did a covert source of money feed his frenzy of acquisition that began in the mid-2000s?

The Times examined and analyzed the data from thousands of individual and business tax returns for 2000 through 2017, along with additional tax information from other years. The trove included years of employee compensation information and records of cash payments between the president and his businesses, as well as information about ongoing federal audits of his taxes. This article also draws upon dozens of interviews and previously unreported material from other sources, both public and confidential.

All of the information The Times obtained was provided by sources with legal access to it. While most of the tax data has not previously been made public, The Times was able to verify portions of it by comparing it with publicly available information and confidential records previously obtained by The Times.

To delve into the records is to see up close the complex structure of the president’s business interests — and the depth of his entanglements. What is popularly known as the Trump Organization is in fact a collection of more than 500 entities, virtually all of them wholly owned by Mr. Trump, many carrying his name. For example, 105 of them are a variation of the name Trump Marks, which he uses for licensing deals.

Fragments of Mr. Trump’s tax returns have leaked out before.

Transcripts of his main federal tax form, the 1040, from 1985 to 1994, were obtained by The Times in 2019. They showed that, in many years, Mr. Trump lost more money than nearly any other individual American taxpayer. Three pages of his 1995 returns, mailed anonymously to The Times during the 2016 campaign, showed that Mr. Trump had declared losses of $915.7 million, giving him a tax deduction that could have allowed him to avoid federal income taxes for almost two decades. Five months later, the journalist David Cay Johnston obtained two pages of Mr. Trump’s returns from 2005; that year, his fortunes had rebounded to the point that he was paying taxes.

The vast new trove of information analyzed by The Times completes the recurring pattern of ascent and decline that has defined the president’s career. Even so, it has its limits.

Tax returns do not, for example, record net worth — in Mr. Trump’s case, a topic of much posturing and almost as much debate. The documents chart a great churn of money, but while returns report debts, they often do not identify lenders.

The data contains no new revelations about the $130,000 payment to Stephanie Clifford, the actress who performs as Stormy Daniels — a focus of the Manhattan district attorney’s subpoena for Mr. Trump’s tax returns and other financial information. Mr. Trump has acknowledged reimbursing his former lawyer, Michael D. Cohen, who made the payoff, but the materials obtained by The Times did not include any itemized payments to Mr. Cohen. The amount, however, could have been improperly included in legal fees written off as a business expense, which are not required to be itemized on tax returns.

No subject has provoked more intense speculation about Mr. Trump’s finances than his connection to Russia. While the tax records revealed no previously unknown financial connection — and, for the most part, lack the specificity required to do so — they did shed new light on the money behind the 2013 Miss Universe pageant in Moscow, a subject of enduring intrigue because of subsequent investigations into Russia’s interference in the 2016 election.

The records show that the pageant was the most profitable Miss Universe during Mr. Trump’s time as co-owner, and that it generated a personal payday of $2.3 million — made possible, at least in part, by the Agalarov family, who would later help set up the infamous 2016 meeting between Trump campaign officials seeking “dirt” on Mrs. Clinton and a Russian lawyer connected to the Kremlin.

In August, the Senate Intelligence Committee released a report that looked extensively into the circumstances of the Moscow pageant, and revealed that as recently as February, investigators subpoenaed the Russian singer Emin Agalarov, who was involved in planning it. Mr. Agalarov’s father, Aras, a billionaire who boasts of close ties to Mr. Putin, was Mr. Trump’s partner in the event.

The committee interviewed a top Miss Universe executive, Paula Shugart, who said the Agalarovs offered to underwrite the event; their family business, Crocus Group, paid a $6 million licensing fee and another $6 million in expenses. But while the pageant proved to be a financial loss for the Agalarovs — they recouped only $2 million — Ms. Shugart told investigators that it was “one of the most lucrative deals” the Miss Universe organization ever made, according to the report.

That is borne out by the tax records. They show that in 2013, the pageant reported $31.6 million in gross receipts — the highest since at least the 1990s — allowing Mr. Trump and his co-owner, NBC, to split profits of $4.7 million. By comparison, Mr. Trump and NBC shared losses of $2 million from the pageant the year before the Moscow event, and $3.8 million from the one the year after.

While Mr. Trump crisscrossed the country in 2015 describing himself as uniquely qualified to be president because he was “really rich” and had “built a great company,” his accountants back in New York were busy putting the finishing touches on his 2014 tax return.

After tabulating all the profits and losses from Mr. Trump’s various endeavors on Form 1040, the accountants came to Line 56, where they had to enter the total income tax the candidate was required to pay. They needed space for only a single figure.

Zero.

For Mr. Trump, that bottom line must have looked familiar. It was the fourth year in a row that he had not paid a penny of federal income taxes.

Mr. Trump’s avoidance of income taxes is one of the most striking discoveries in his tax returns, especially given the vast wash of income itemized elsewhere in those filings.

Mr. Trump’s net income from his fame — his 50 percent share of “The Apprentice,” together with the riches showered upon him by the scores of suitors paying to use his name — totaled $427.4 million through 2018. A further $176.5 million in profit came to him through his investment in two highly successful office buildings.

So how did he escape nearly all taxes on that fortune? Even the effective tax rate paid by the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans could have caused him to pay more than $100 million.

The answer rests in a third category of Mr. Trump’s endeavors: businesses that he owns and runs himself. The collective and persistent losses he reported from them largely absolved him from paying federal income taxes on the $600 million from “The Apprentice,” branding deals and investments.

That equation is a key element of the alchemy of Mr. Trump’s finances: using the proceeds of his celebrity to purchase and prop up risky businesses, then wielding their losses to avoid taxes.

Throughout his career, Mr. Trump’s business losses have often accumulated in sums larger than could be used to reduce taxes on other income in a single year. But the tax code offers a workaround: With some restrictions, business owners can carry forward leftover losses to reduce taxes in future years.

That provision has been the background music to Mr. Trump’s life. As The Times’s previous reporting on his 1995 return showed, the nearly $1 billion in losses from his early-1990s collapse generated a tax deduction that he could use for up to 18 years going forward.

The newer tax returns show that Mr. Trump burned through the last of the tax-reducing power of that $1 billion in 2005, just as a torrent of entertainment riches began coming his way following the debut of “The Apprentice” the year before.

For 2005 through 2007, cash from licensing deals and endorsements filled Mr. Trump’s bank accounts with $120 million in pure profit. With no prior-year losses left to reduce his taxable income, he paid substantial federal income taxes for the first time in his life: a total of $70.1 million.

As his celebrity income swelled, Mr. Trump went on a buying spree unlike any he had had since the 1980s, when eager banks and his father’s wealth allowed him to buy or build the casinos, airplanes, yacht and old hotel that would soon lay him low.

When “The Apprentice” premiered, Mr. Trump had opened only two golf courses and was renovating two more. By the end of 2015, he had 15 courses and was transforming the Old Post Office building in Washington into a Trump International Hotel. But rather than making him wealthier, the tax records reveal as never before, each new acquisition only fed the downward draft on his bottom line.

Consider the results at his largest golf resort, Trump National Doral, near Miami. Mr. Trump bought the resort for $150 million in 2012; through 2018, his losses have totaled $162.3 million. He has pumped $213 million of fresh cash into Doral, tax records show, and has a $125 million mortgage balance coming due in three years.

His three courses in Europe — two in Scotland and one in Ireland — have reported a combined $63.6 million in losses.

Over all, since 2000, Mr. Trump has reported losses of $315. 6 million at the golf courses that are his prized possessions.

For all of its Trumpworld allure, his Washington hotel, opened in 2016, has not fared much better. Its tax records show losses through 2018 of $55.5 million.

And Trump Corporation, a real estate services company, has reported losing $134 million since 2000. Mr. Trump personally bankrolled the losses year after year, marking his cash infusions as a loan with an ever-increasing balance, his tax records show. In 2016, he gave up on getting paid back and turned the loan into a cash contribution.

Mr. Trump has often posited that his losses are more accounting magic than actual money out the door.

Last year, after The Times published details of his tax returns from the 1980s and 1990s, he attributed the red ink to depreciation, which he said in a tweet would show “losses in almost all cases” and that “much was non monetary.”

“I love depreciation,” Mr. Trump said during a presidential debate in 2016.

Depreciation, though, is not a magic wand — it involves real money spent or borrowed to buy buildings or other assets that are expected to last years. Those costs must be spread out as expenses and deducted over the useful life of the asset. Even so, the rules do hold particular advantages for real estate developers like Mr. Trump, who are allowed to use their real estate losses to reduce their taxable income from other activities.

What the tax records for Mr. Trump’s businesses show, however, is that he has lost chunks of his fortune even before depreciation is figured in. The three European golf courses, the Washington hotel, Doral and Trump Corporation reported losing a total of $150.3 million from 2010 through 2018, without including depreciation as an expense.

To see what a successful business looks like, depreciation or not, look no further than one in Mr. Trump’s portfolio that he does not manage.

After plans for a Trump-branded mini-city on the Far West Side of Manhattan stalled in the 1990s, Mr. Trump’s stake was sold by his partner to Vornado Realty Trust. Mr. Trump objected to the sale in court, saying he had not been consulted, but he ended up with a 30 percent share of two valuable office buildings owned and operated by Vornado.

His share of the profits through the end of 2018 totaled $176.5 million, with depreciation factored in. He has never had to invest more money in the partnership, tax records show.

Among businesses he runs, Mr. Trump’s first success remains his best. The retail and commercial spaces at Trump Tower, completed in 1983, have reliably delivered more than $20 million a year in profits, a total of $336.3 million since 2000 that has done much to help keep him afloat.

Mr. Trump has an established track record of stiffing his lenders. But the tax returns reveal that he has failed to pay back far more money than previously known: a total of $287 million since 2010.

The I.R.S. considers forgiven debt to be income, but Mr. Trump was able to avoid taxes on much of that money by reducing his ability to declare future business losses. For the rest, he took advantage of a provision of the Great Recession bailout that allowed income from canceled debt to be completely deferred for five years, then spread out evenly over the next five. He declared the first $28.2 million in 2014.

Once again, his business losses mostly absolved his tax responsibilities. He paid no federal income taxes for 2014.

Mr. Trump was periodically required to pay a parallel income tax called the alternative minimum tax, created as a tripwire to prevent wealthy people from using huge deductions, including business losses, to entirely wipe out their tax liabilities.

Mr. Trump paid alternative minimum tax in seven years between 2000 and 2017 — a total of $24.3 million, excluding refunds he received after filing. For 2015, he paid $641,931, his first payment of any federal income tax since 2010.

As he settled into the Oval Office, his tax bills soon returned to form. His potential taxable income in 2016 and 2017 included $24.8 million in profits from sources related to his celebrity status and $56.4 million for the loans he did not repay. The dreaded alternative minimum tax would let his business losses erase only some of his liability.

Each time, he requested an extension to file his 1040; and each time, he made the required payment to the I.R.S. for income taxes he might owe — $1 million for 2016 and $4.2 million for 2017. But virtually all of that liability was washed away when he eventually filed, and most of the payments were rolled forward to cover potential taxes in future years.

To cancel out the tax bills, Mr. Trump made use of $9.7 million in business investment credits, at least some of which related to his renovation of the Old Post Office hotel, which qualified for a historic-preservation tax break. Although he had more than enough credits to owe no taxes at all, his accountants appear to have carved out an allowance for a small tax liability for both 2016 and 2017.

When they got to line 56, the one for income taxes due, the amount was the same each year: $750.

The $72.9 Million Maneuver

“The Apprentice” created what was probably the biggest income tax bite of Mr. Trump’s life. During the Great Recession bailout, he asked for the money back.

Testifying before Congress in February 2019, the president’s estranged personal lawyer, Mr. Cohen, recalled Mr. Trump’s showing him a huge check from the U.S. Treasury some years earlier and musing “that he could not believe how stupid the government was for giving someone like him that much money back.”

In fact, confidential records show that starting in 2010 he claimed, and received, an income tax refund totaling $72.9 million — all the federal income tax he had paid for 2005 through 2008, plus interest.

The legitimacy of that refund is at the center of the audit battle that he has long been waging, out of public view, with the I.R.S.

The records that The Times reviewed square with the way Mr. Trump has repeatedly cited, without explanation, an ongoing audit as grounds for refusing to release his tax returns. He alluded to it as recently as July on Fox News, when he told Sean Hannity, “They treat me horribly, the I.R.S., horribly.”

And while the records do not lay out all the details of the audit, they match his lawyers’ statement during the 2016 campaign that audits of his returns for 2009 and subsequent years remained open, and involved “transactions or activities that were also reported on returns for 2008 and earlier.”

Mr. Trump harvested that refund bonanza by declaring huge business losses — a total of $1.4 billion from his core businesses for 2008 and 2009 — that tax laws had prevented him from using in prior years.

But to turn that long arc of failure into a giant refund check, he relied on some deft accounting footwork and an unwitting gift from an unlikely source — Mr. Obama.

Business losses can work like a tax-avoidance coupon: A dollar lost on one business reduces a dollar of taxable income from elsewhere. The types and amounts of income that can be used in a given year vary, depending on an owner’s tax status. But some losses can be saved for later use, or even used to request a refund on taxes paid in a prior year.

Until 2009, those coupons could be used to wipe away taxes going back only two years. But that November, the window was more than doubled by a little-noticed provision in a bill Mr. Obama signed as part of the Great Recession recovery effort. Now business owners could request full refunds of taxes paid in the prior four years, and 50 percent of those from the year before that.

Mr. Trump had paid no income taxes in 2008. But the change meant that when he filed his taxes for 2009, he could seek a refund of not just the $13.3 million he had paid in 2007, but also the combined $56.9 million paid in 2005 and 2006, when “The Apprentice” created what was likely the biggest income tax bite of his life.

The records reviewed by The Times indicate that Mr. Trump filed for the first of several tranches of his refund several weeks later, in January 2010. That set off what tax professionals refer to as a “quickie refund,” a check processed in 90 days on a tentative basis, pending an audit by the I.R.S.

His total federal income tax refund would eventually grow to $70.1 million, plus $2,733,184 in interest. He also received $21.2 million in state and local refunds, which often piggyback on federal filings.

Whether Mr. Trump gets to keep the cash, though, remains far from a sure thing.

Refunds require the approval of I.R.S. auditors and an opinion of the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation, a bipartisan panel better known for reviewing the impact of tax legislation. Tax law requires the committee to weigh in on all refunds larger than $2 million to individuals.

Records show that the results of an audit of Mr. Trump’s refund were sent to the joint committee in the spring of 2011. An agreement was reached in late 2014, the documents indicate, but the audit resumed and grew to include Mr. Trump’s returns for 2010 through 2013. In the spring of 2016, with Mr. Trump closing in on the Republican nomination, the case was sent back to the committee. It has remained there, unresolved, with the statute of limitations repeatedly pushed forward.

Precisely why the case has stalled is not clear. But experts say it suggests that the gap between the sides remains wide. If negotiations were to deadlock, the case would move to federal court, where it could become a matter of public record.

The dispute may center on a single claim that jumps off the page of Mr. Trump’s 2009 tax return: a declaration of more than $700 million in business losses that he had not been allowed to use in prior years. Unleashing that giant tax-avoidance coupon enabled him to receive some or all of his refund.

The material obtained by The Times does not identify the business or businesses that generated those losses. But the losses were a kind that can be claimed only when partners give up their interest in a business. And in 2009, Mr. Trump parted ways with a giant money loser: his long-failing Atlantic City casinos.

After Mr. Trump’s bondholders rebuffed his offer to buy them out, and with a third round of bankruptcy only a week away, Mr. Trump announced in February 2009 that he was quitting the board of directors.

“If I’m not going to run it, I don’t want to be involved in it,” he told The Associated Press. “I’m one of the largest developers in the world. I have a lot of cash and plenty of places I can go.”

The same day, he notified the Securities and Exchange Commission that he had “determined that his partnership interests are worthless and lack potential to regain value” and was “hereby abandoning” his stake.

The language was crucial. Mr. Trump was using the precise wording of I.R.S. rules governing the most beneficial, and perhaps aggressive, method for business owners to avoid taxes when separating from a business.

A partner who walks away from a business with nothing — what tax laws refer to as abandonment — can suddenly declare all the losses on the business that could not be used in prior years. But there are a few catches, including this: Abandonment is essentially an all-or-nothing proposition. If the I.R.S. learns that the owner received anything of value, the allowable losses are reduced to just $3,000 a year.

And Mr. Trump does appear to have received something. When the casino bankruptcy concluded, he got 5 percent of the stock in the new company. The materials reviewed by The Times do not make clear whether Mr. Trump’s refund application reflected his public declaration of abandonment. If it did, that 5 percent could place his entire refund in question.

If the auditors ultimately disallow Mr. Trump’s $72.9 million federal refund, he will be forced to return that money with interest, and possibly penalties, a total that could exceed $100 million. He could also be ordered to return the state and local refunds based on the same claims.

In response to a question about the audit, Mr. Garten, the Trump Organization lawyer, said facts cited by The Times were incorrect, without citing specifics. He did, however, write that it was “illogical” to say Mr. Trump had not paid taxes for those three years just because the money was later refunded.

“While you claim that President Trump paid no taxes in 10 of the 15 previous years,” Mr. Garten said, “you also assert that President Trump claimed a massive refund for tens of millions for taxes he did pay. These two claims are entirely inconsistent and, in any event, not supported by the facts.”

House Democrats who have been in hot pursuit of Mr. Trump’s tax returns most likely have no idea that at least some of the records are sitting in a congressional office building. George Yin, a former chief of staff for the joint committee, said that any identifying information about taxpayers under review was tightly held among a handful of staff lawyers and was rarely shared with politicians assigned to the committee.

It is possible that the case has been paused because Mr. Trump is president, which would raise the personal stakes of re-election. If the recent Fox interview is any indication, Mr. Trump seems increasingly agitated about the matter.

“It’s a disgrace what’s happened,” he told Mr. Hannity. “We had a deal done. In fact, it was — I guess it was signed even. And once I ran, or once I won, or somewhere back a long time ago, everything was like, ‘Well, let’s start all over again.’ It’s a disgrace.”

The 20 Percent Solution

Helping to reduce Mr. Trump’s tax bills are unidentified consultants’ fees, some of which can be matched to payments received by Ivanka Trump.

Examining the Trump Organization’s tax records, a curious pattern emerges: Between 2010 and 2018, Mr. Trump wrote off some $26 million in unexplained “consulting fees” as a business expense across nearly all of his projects.

In most cases the fees were roughly one-fifth of his income: In Azerbaijan, Mr. Trump collected $5 million on a hotel deal and reported $1.1 million in consulting fees, while in Dubai it was $3 million with a $630,000 fee, and so on.

Mysterious big payments in business deals can raise red flags, particularly in places where bribes or kickbacks to middlemen are routine. But there is no evidence that Mr. Trump, who mostly licenses his name to other people’s projects and is not involved in securing government approvals, has engaged in such practices.

Rather, there appears to be a closer-to-home explanation for at least some of the fees: Mr. Trump reduced his taxable income by treating a family member as a consultant, and then deducting the fee as a cost of doing business.

The “consultants” are not identified in the tax records. But evidence of this arrangement was gleaned by comparing the confidential tax records to the financial disclosures Ivanka Trump filed when she joined the White House staff in 2017. Ms. Trump reported receiving payments from a consulting company she co-owned, totaling $747,622, that exactly matched consulting fees claimed as tax deductions by the Trump Organization for hotel projects in Vancouver and Hawaii.

Ms. Trump had been an executive officer of the Trump companies that received profits from and paid the consulting fees for both projects — meaning she appears to have been treated as a consultant on the same hotel deals that she helped manage as part of her job at her father’s business.

When asked about the arrangement, the Trump Organization lawyer, Mr. Garten, did not comment.

Employers can deduct consulting fees as a business expense and also avoid the withholding taxes that apply to wages. To claim the deduction, the consulting arrangement must be an “ordinary and necessary” part of running the business, with fees that are reasonable and market-based, according to the I.R.S. The recipient of the fees is still required to pay income tax.

The I.R.S. has pursued civil penalties against some business owners who devised schemes to avoid taxes by paying exorbitant fees to related parties who were not in fact independent contractors. A 2011 tax court case centered on the I.R.S.’s denial of almost $3 million in deductions for consulting fees the partners in an Illinois accounting firm paid themselves via corporations they created. The court concluded that the partners had structured the fees to “distribute profits, not to compensate for services.”

There is no indication that the I.R.S. has questioned Mr. Trump’s practice of deducting millions of dollars in consulting fees. If the payments to his daughter were compensation for work, it is not clear why Mr. Trump would do it in this form, other than to reduce his own tax liability. Another, more legally perilous possibility is that the fees were a way to transfer assets to his children without incurring a gift tax.

A Times investigation in 2018 found that Mr. Trump’s late father, Fred Trump, employed a number of legally dubious schemes decades ago to evade gift taxes on millions of dollars he transferred to his children. It is not possible to discern from this newer collection of tax records whether intra-family financial maneuverings were a motivating factor.

However, the fact that some of the consulting fees are identical to those reported by Mr. Trump’s daughter raises the question of whether this was a mechanism the president used to compensate his adult children involved with his business. Indeed, in some instances where large fees were claimed, people with direct knowledge of the projects were not aware of any outside consultants who would have been paid.

On the failed hotel deal in Azerbaijan, which was plagued by suspicions of corruption, a Trump Organization lawyer told The New Yorker the company was blameless because it was merely a licenser and had no substantive role, adding, “We did not pay any money to anyone.” Yet, the tax records for three Trump L.L.C.s involved in that project show deductions for consulting fees totaling $1.1 million that were paid to someone.

In Turkey, a person directly involved in developing two Trump towers in Istanbul expressed bafflement when asked about consultants on the project, telling The Times there was never any consultant or other third party in Turkey paid by the Trump Organization. But tax records show regular deductions for consulting fees over seven years totaling $2 million.

Ms. Trump disclosed in her public filing that the fees she received were paid through TTT Consulting L.L.C., which she said provided “consulting, licensing and management services for real estate projects.” Incorporated in Delaware in December 2005, the firm is one of several Trump-related entities with some variation of TTT or TTTT in the name that appear to refer to members of the Trump family.

Like her brothers Donald Jr. and Eric, Ms. Trump was a longtime employee of the Trump Organization and an executive officer for more than 200 Trump companies that licensed or managed hotel and resort properties. The tax records show that the three siblings had each drawn a salary from their father’s company — roughly $480,000 a year, jumping to about $2 million after Mr. Trump became president — though Ms. Trump no longer receives a salary. What’s more, Mr. Trump has said the children were intimately involved in negotiating and managing his projects. When asked in a 2011 lawsuit deposition whom he relied on to handle important details of his licensing deals, he named only Ivanka, Donald Jr. and Eric.

On Ms. Trump’s now-defunct website, which explains her role at the Trump Organization, she was not identified as a consultant. Rather, she has been described as a senior executive who “actively participates in all aspects of both Trump and Trump branded projects, including deal evaluation, predevelopment planning, financing, design, construction, sales and marketing, and ensuring that Trump’s world-renowned physical and operational standards are met.

“She is involved in all decisions — large and small.”

The Art of the Write-Off

Hair stylists, table linens, property taxes on a family estate — all have been deducted as business expenses.

Private jets, country clubs and mansions have all had a role in the selling of Donald Trump.

“I play to people’s fantasies,” he wrote in “Trump: The Art of the Deal.” “People want to believe that something is the biggest and the greatest and the most spectacular. I call it truthful hyperbole. It’s an innocent form of exaggeration — and a very effective form of promotion.”

If the singular Trump product is Trump in an exaggerated form — the man, the lifestyle, the acquisitiveness — then everything that feeds the image, including the cost of his businesses, can be written off on his taxes. Mr. Trump may be reporting business losses to the government, but he can still live a life of wealth and write it off.

Take, for example, Mar-a-Lago, now the president’s permanent residence as well as a private club and stage set on which Trump luxury plays out. As a business, it is also the source of millions of dollars in expenses deducted from taxable income, among them $109,433 for linens and silver and $197,829 for landscaping in 2017. Also deducted as a business expense was the $210,000 paid to a Florida photographer over the years for shooting numerous events at the club, including a 2016 New Year’s Eve party hosted by Mr. Trump.

Mr. Trump has written off as business expenses costs — including fuel and meals — associated with his aircraft, used to shuttle him among his various homes and properties. Likewise the cost of haircuts, including the more than $70,000 paid to style his hair during “The Apprentice.” Together, nine Trump entities have written off at least $95,464 paid to a favorite hair and makeup artist of Ivanka Trump.

In allowing business expenses to be deducted, the I.R.S. requires that they be “ordinary and necessary,” a loosely defined standard often interpreted generously by business owners.

Perhaps Mr. Trump’s most generous interpretation of the business expense write-off is his treatment of the Seven Springs estate in Westchester County, N.Y.

Seven Springs is a throwback to another era. The main house, built in 1919 by Eugene I. Meyer Jr., the onetime head of the Federal Reserve who bought The Washington Post in 1933, sits on more than 200 acres of lush, almost untouched land just an hour’s drive north of New York City.

“The mansion is 50,000 square feet, has three pools, carriage houses, and is surrounded by nature preserves,” according to The Trump Organization website.

Mr. Trump had big plans when he bought the property in 1996 — a golf course, a clubhouse and 15 private homes. But residents of surrounding towns thwarted his ambitions, arguing that development would draw too much traffic and risk polluting the drinking water.

Mr. Trump instead found a way to reap tax benefits from the estate. He took advantage of what is known as a conservation easement. In 2015, he signed a deal with a land conservancy, agreeing not to develop most of the property. In exchange, he claimed a $21.1 million charitable tax deduction.

The tax records reveal another way Seven Springs has generated substantial tax savings. In 2014, Mr. Trump classified the estate as an investment property, as distinct from a personal residence. Since then, he has written off $2.2 million in property taxes as a business expense — even as his 2017 tax law allowed individuals to write off only $10,000 in property taxes a year.

Courts have held that to treat residences as businesses for tax purposes, owners must show that they have “an actual and honest objective of making a profit,” typically by making substantial efforts to rent the property and eventually generating income.

Whether or not Seven Springs fits those criteria, the Trumps have described the property somewhat differently.

In 2014, Eric Trump told Forbes that “this is really our compound.” Growing up, he and his brother Donald Jr. spent many summers there, riding all-terrain vehicles and fishing on a nearby lake. At one point, the brothers took up residence in a carriage house on the property. “It was home base for us for a long, long time,” Eric told Forbes.

And the Trump Organization website still describes Seven Springs as a “retreat for the Trump family.”

Mr. Garten, the Trump Organization lawyer, did not respond to a question about the Seven Springs write-off.

The Seven Springs conservation-easement deduction is one of four that Mr. Trump has claimed over the years. While his use of these deductions is widely known, his tax records show that they represent the lion’s share of his charitable giving — about $119.3 million of roughly $130 million in personal and corporate charitable contributions reported to the I.R.S.

Two of those deductions — at Seven Springs and at the Trump National Golf Club in Los Angeles — are the focus of an investigation by the New York attorney general, who is examining whether the appraisals on the land, and therefore the tax deductions, were inflated.

Another common deductible expense for all businesses is legal fees. The I.R.S. requires that these fees be “directly related to operating your business,” and businesses cannot deduct “legal fees paid to defend charges that arise from participation in a political campaign.”

Yet the tax records show that the Trump Corporation wrote off as business expenses fees paid to a criminal defense lawyer, Alan S. Futerfas, who was hired to represent Donald Trump Jr. during the Russia inquiry. Investigators were examining Donald Jr.’s role in the 2016 Trump Tower meeting with Russians who had promised damaging information on Mrs. Clinton. When he testified before Congress in 2017, Mr. Futerfas was by his side.