The new guidance.

Sideshow Rudy gets Covid -

Is it true?? I’ve gotten so cynical these 4 years, I think he might have already had it (when he was practicing w/ T on his debates) but Rudy needs and easy “out” that would get him out of the multiple (by 10’s) lost ‘voter fraud’ lawsuits.

Just a thought. This administration will do and say anything…

Yes it is true…he has gone to the hospital

Rudy’s appearances results in this…

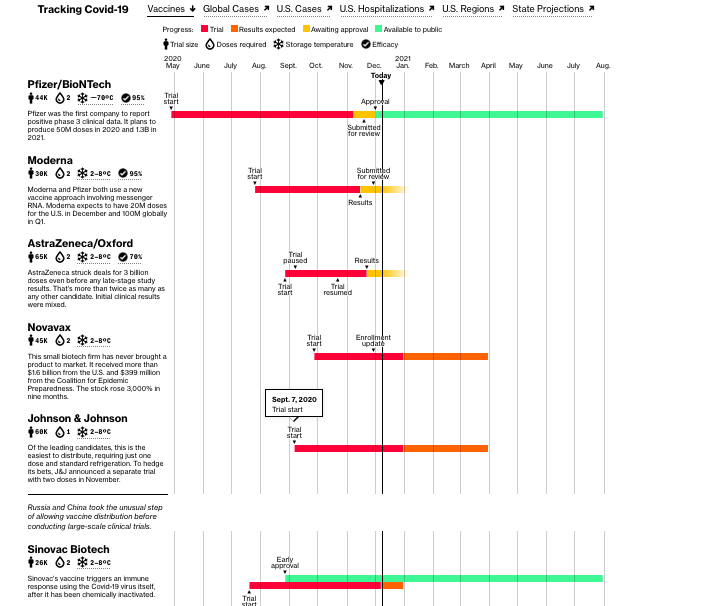

Where we are with the distribution of the vaccine…Not sure why the heading on this Bloomberg article is hard to load…but from Bloomberg.com

LInks here.

She was the whistleblower in Florida, telling the people that the Covid infection numbers were being underreported. She went home and continued to send out the infection rates, based on her data technology techniques. Today her house was raided and she was met with a gunpoint

checking her ‘data.’

Florida Department of Law Enforcement agents on Monday raided, at gunpoint, the home of the former Department of Health employee who had claimed she’d been told to censor COVID-19 data before being fired in May.

Since her ouster, Rebekah Jones has been a vocal critic of Gov. Ron DeSantis’ handling of the pandemic, as cases soared and he refused to issue a mask mandate, among other preventative measures that could have saved lives.

The state said authorities were investigating whether Jones is the one who hacked into the state’s emergency communications channel to send a message that urged people to “speak up before another 17,000 people are dead,” the Tampa Bay Times reported last month.

Operation Warp Speed is standing still.

It’s highly contagious…(so is stupidity) Trump ‘lawyer’ Jenna Ellis gets Covid

How many tons of karma dumped on T’s legal team now?

One Pfizer trial participant told CNBC that after the second shot, he woke up with chills, shaking so hard he cracked a tooth. “It hurt to even just lay in my bed sheet,” he said.

Many people are now wondering whether this will be just like getting the flu vaccine.

The short answer is: No, not really.If Pfizer’s shot is granted an emergency use authorization, or EUA, the immunizations — which are administered in two doses about three weeks apart — could start as soon as next week.

Others experienced headaches and fatigue.The FDA said that while side effects of the Pfizer vaccine are common, there are “no specific safety concerns identified that would preclude issuance of an EUA.”

Be prepared for the second shot

The Pfizer vaccine is one of four U.S.-backed candidates in phase three trials. Next up is one from U.S. biotech firm Moderna, which has also submitted its EUA application.

Both companies have said that taking their vaccines could result in side effects similar to mild Covid symptoms. Think muscle pain, chills and a headache.

When trial participant Yasir Batalvi first read Moderna’s 22-page consent form warning of side effects ranging from nothing at all to death, he felt pretty worried, he told CNBC.

“You have to keep in mind, I joined the trial when we didn’t know it was going to be a safe vaccine,” said Batalvi, a recent college graduate living in Boston.

The 24-year-old said that when he got the first injection in mid-October, it felt just like a flu shot. “I experienced stiffness and pain in my left arm where I had gotten the shot, but it was mild,” he explained. “By that evening, I didn’t want to move my arm above my shoulder, but it was localized, and it disappeared by the next day.”

The second dose was a different story.

“After the injection, I had the same side effects as the first: localized pain and stiffness, but it was a little bit worse. My arm got sore faster, and by the time I got home, I started feeling fatigued and like anyone would feel if they were coming down with the flu,” said Batalvi.

More significant symptoms presented that evening. “I developed a low-grade fever and had chills,” he said. “That evening was rough.”

After a restless night, he called the study doctors, who reassured him it was a normal reaction and no cause for concern. By that afternoon, Batalvi said, he felt like himself again.

Moderna stopped testing the highest dose of its vaccine during the trial because of the number of reports of severe adverse reactions.

As for any long-term effects, Batalvi isn’t giving it much thought. “I’m not too concerned,” he said. “We know from vaccination trials that any adverse events mostly show up in the first couple of months.”

House Oversight Committee Chair: Testimony Points To Political Interference At CDC

A new kerfuffle is unfolding in a House oversight committee with the Democratic chair accusing White House appointees of political meddling and attempting to influence the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention strategies on the coronavirus pandemic in a manner that paints the administration in a more favorable light.

In a Thursday letter to the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, Rep. James Clyburn expressed “serious concern about what may be deliberate efforts by the Trump Administration to conceal and destroy evidence that senior political appointees interfered with career officials’ response to the coronavirus crisis” at the CDC.

Clyburn, a Democrat from South Carolina, chairs the Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis. In addition to HHS Secretary Alex Azar, the letter was also addressed to CDC Director Robert Redfield.

Clyburn suggested Redfield may have instructed subordinates to delete an email from an HHS appointee instructing the CDC to alter or rescind reports believed to be damaging to President Trump. The congressman also accused Redfield of pushing back the publication of a report on a coronavirus outbreak among children in Georgia so that the White House could continue to push for school reopenings.

The allegations stem from the transcribed interview of Charlotte Kent, chief of the Scientific Publications Branch and editor-in-chief of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report at the CDC, who addressed Select Subcommittee staff on Monday. During her testimony, Kent said she was instructed to delete an Aug. 8 email sent by HHS senior advisor Paul Alexander, and that she understood the direction came from the CDC head Redfield.

As she recounted the incident, Alexander’s email demanded that the CDC insert new language in a previously published scientific report on coronavirus risks to children or “pull it down and stop all reports immediately,” according to Clyburn.

The letter says Alexander also vented about alleged bias within the CDC against Trump: “CDC tried to report as if once kids get together, there will be spread and this will impact school reopening. … Very misleading by CDC and shame on them. Their aim is clear. … This is designed to hurt this Presidnet [sic] for their reasons which I am not interested in.”

Alexander, who served as a scientific advisor to HHS spokesman Michael Caputo, is no longer with the department. He left in September and is now is an assistant professor of health research at McMaster University near Toronto. Caputo formerly served as a Trump campaign official. He has no medical or scientific background.

This is not the first time Alexander has been called out as improperly trying to influence the nation’s leading health officials. In September, Politico uncovered emails showing Alexander tried to prevent Anthony Fauci, the government’s top infectious disease expert, from speaking about the risks that coronavirus poses to children.

Earlier this week, Kent explained that when she later searched for the email it had already vanished. Federal employees must generally preserve documents under the Federal Records Act. When asked, she said she did not know who had deleted the correspondence.

On Thursday Clyburn said the Trump Administration’s “political meddling with the nation’s coronavirus response has put American lives at greater risk,” and called the efforts “dangerous.” He called for all documents to be preserved or recovered.

House Republicans on the Select Subcommittee, including ranking member Steve Scalise of Louisiana, called Clyburn’s allegations false, adding that all stonewalling claims have been debunked.

“The Select Subcommittee Democrats’ letter drastically mischaracterizes Dr. Kent’s interview,” Scalise wrote in a statement.

“The letter fails to acknowledge the predicate of the Democrats’ investigation is now fully debunked. Despite there being zero evidence of actual interference in CDC scientific reports, Select Subcommittee Democrats continue to search for illusory evidence in obstruction of the Trump Administration’s unprecedented whole-of-America response to the coronavirus pandemic.”

He added that during Monday’s testimony, Kent, a career CDC official, “unequivocally confirmed that there was no political interference and the scientific integrity of the MMWR was never compromised.”

“Case closed,” he declared.

Redfield also addressed the allegations on Thursday, issuing a statement that reads: “Regarding the email in question, I instructed CDC staff to ignore Dr. Alexander’s comments.”

“As I testified before Congress, I am fully committed to maintaining the independence of the MMWR, and I stand by that statement.”

Meanwhile, Clyburn is now seeking to interview Redfield about the incident.

He says that hours after Kent’s testimony, HHS “abruptly canceled” four additional transcribed interviews the select subcommittee had scheduled for the week. Clyburn called it part of a broader pattern of “obstruction” and warned that if the Department failed to produce all missing documents by Dec. 15, “the Select Subcommittee will have no choice but to issue subpoenas to compel production.”

U.S. Government May Find It Hard To Get More Doses Of Pfizer’s COVID-19 Vaccine

With Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine poised for Food and Drug Administration authorization for emergency use, there’s speculation about when the United States will buy another batch of doses — and whether the Trump administration already missed its chance.

Although a Pfizer board member says the government declined to buy more doses beyond the initial 100 million agreed upon in July, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar told PBS Newshour that this is inaccurate. The company never made a formal offer saying how many doses it would deliver and when — two things that are needed to sign an additional deal.

“They refused to commit to any other production or delivery by a time certain,” he said, explaining that the initial doses will be delivered by March, and there is an option for the government to buy another 500 million after that. “I’m certainly not going to sign a deal with Pfizer, giving them $10 billion to buy vaccine that they could deliver to us five, 10 years hence. That doesn’t make any sense.”

Azar said the government started new negotiations with Pfizer in early October, but “they still resisted giving us any date by which they would do it.” He said they’re making progress in their negotiations, but the government is willing to use “every power of the Defense Production Act” to get the additional necessary Pfizer vaccine doses.

Pfizer board member and former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb told CNBC Tuesday that the federal government declined “multiple times” to purchase more doses of Pfizer’s vaccine over the summer, and it may have missed out on getting more in the second quarter of 2021.

“Pfizer did offer an additional allotment coming out of that plan — basically the second quarter allotment — multiple times,” Gottlieb told CNBC.

Gottlieb noted that the government has agreements to buy hundreds of millions of doses of vaccines from six manufacturers as part of Operation Warp Speed, the Trump administration’s more than $10 billion push to make a coronavirus vaccine available in record time. He suspects the government is betting more than one vaccine would ultimately get the FDA’s authorization.

“That perhaps could be why they didn’t take up that additional 100 million option agreement, which really wouldn’t have required necessarily them to front money. It was just an agreement that they would purchase those vaccines,” Gottlieb said. “So Pfizer has gone ahead and entered into some agreements with other countries to sell them some of that vaccine in the second quarter of 2021.”

And that could mean there’s less available for the U.S. government to buy when it’s ready to do so.

The New York Times first reported Monday on the negotiations for more doses, saying that Pfizer offered the U.S. government between 100 million and 500 million additional doses and warned that its vaccine could be in short supply, given demand around the world. As a result, a second allotment might not be available to the U.S. until next June.

A senior administration official told reporters during a briefing Monday that the Times reporting wasn’t accurate: “We’re in the middle of a negotiation right now and we can’t talk publicly about it, but we feel absolutely confident we will get the vaccine doses for which we’ve contracted and will have a sufficient number of doses to vaccinate all Americans who desire one before the end of second quarter 2021.”

A spokesperson for HHS echoed that explanation in a series of tweets on Tuesday, saying, “At no time did OWS turn down an offer from Pfizer for any number of millions of doses having a firm delivery date and quantity, and it’s a shame that someone is misinforming the American public.”

Pfizer didn’t respond to NPR’s request for comment on this story.

In July, Pfizer signed a $1.95 billion agreement with Operation Warp Speed. As part of the deal, the government agreed to purchase 100 million doses of Pfizer’s vaccine, but the transaction would occur only if the vaccine Pfizer is developing in partnership with BioNTech, a German company, received the FDA’s OK.

It’s not unusual for a company under contract with the government to suggest a modification, such as more doses in the first allotment, said Franklin Turner, a partner at McCarter & English who specializes in government contracting. But there can be any number of reasons the government might decline.

“If I had a dime for every time the government took a step or a position that seems counterintuitive and quite frankly, mind-boggling, I’d be a very rich human being at this point in my life,” Franklin said.

Pfizer’s vaccine could be given the green light this week. A panel of outside experts is set to convene on Thursday and advise the FDA on whether to authorize the vaccine for emergency use in the pandemic.

It’s possible the government could have gotten better follow-on delivery contract terms to begin with, said James Love, director of Knowledge Ecology International. Though he noted that the intellectual property rights in the contract aren’t particularly favorable to the federal government either, as NPR has reported. “At some point, not placing orders when the whole world is placing orders, was a mistake,” Love said.

If the U.S. did miss out on more doses because it declined them, it would be “a spectacular failure,” said Rena Conti, a health economist at Boston University.

“Contracts are forward-looking, that means we could have (and did) sign contracts with other manufacturers that reserve future capacity when it became available,” she said. “We should have [been] including language in every contract reserving the rights to more quantity in advance at a given price.”

Although the Pfizer contract includes the option to buy an additional 500 million doses of its vaccine, that transaction would require a separate agreement, and the price would be subject to change, the contract says.

“Having more quantity reserved is smart economics given the uncertainty entailed in which vaccine comes to market in a given time period, and which vaccine will be most safe, [effective] and able to manufacture at scale,” Conti said. “There is no downside cost or risk to having these forward contracts and there is plenty to gain for the American public.”

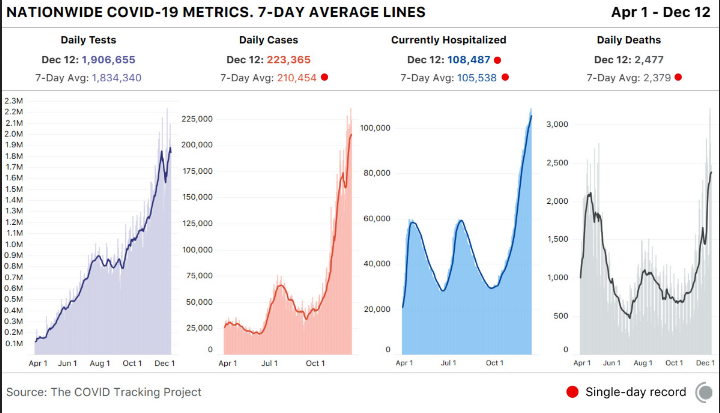

The Covid numbers are way too scary. 12/12/20

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EpE6qJYVgAAPo8b?format=jpg&name=4096x4096

White House staff members will be among the first to be vaccinated.

White House staff members who work in close quarters with President Trump have been told they are scheduled to receive injections of the coronavirus vaccine soon, at a time when the first doses of the vaccine are being distributed only to high-risk health care workers, according to two sources familiar with the distribution plans.

The goal of distributing the vaccine inside the West Wing is to prevent additional government officials from falling ill in the final weeks of the Trump administration. The hope is to eventually distribute the vaccine to everyone who works in the White House, but will begin with some of the most senior people who work around the president, one of the people said.

And then Trump immediately rescinded this. Bizarre.

Covid ‘D-Day’: ICU nurse in New York among first in country to receive vaccination

“D-Day was a pivotal turning point in World War II. It was the beginning of the end — and that’s where we are today,” Gen. Gustave Perna said.

Sadly…we hit 300,000 number of deaths from Covid. Vaccine can not get here sooner…but many months off for the country for herd immunity (more than 70%)

This Atlantic article covers a lot of ground about how the vaccines will get distributed, and who will be getting them.

With the FDA’s emergency authorization of the first COVID-19 vaccine imminent, the biggest and most complex vaccination campaign in the nation’s history is gearing into action. Planes are ferrying vaccines around the country, hospitals are readying ultracold freezers, and the very first people outside of clinical trials will soon get shots in their arms. The end of the pandemic is in sight.

But vaccines are not an off switch. It will take several months to vaccinate enough Americans to resume normal life, and this interim could prove long, confusing, and chaotic. The next six months will almost certainly bring delays in vaccine timelines, fights over vaccine priority, and questions about how immune the newly vaccinated are and how they should behave. We’ve spent 2020 adjusting to a pandemic normal, and now a strange, new period is upon us. Call it vaccine purgatory.

The biggest unknown is how long we will be left in purgatory. Operation Warp Speed officials have laid out an aggressive timeline to get nearly all Americans vaccinated by June, but this presumes several pieces going perfectly. The Pfizer vaccine, which was just recommended for FDA authorization, and the Moderna vaccine, which is expected to follow next week, cannot hit manufacturing delays, and additional vaccine candidates, from AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson, must earn speedy authorization from the FDA early next year. Pfizer earlier revised down the number of doses it will deliver in 2020 and separately has said it cannot supply any additional doses to the U.S., beyond the 100 million already ordered, before June. The timeline for authorizing AstraZeneca’s vaccine is up in the air after a messy clinical trial. And Johnson & Johnson’s has not yet been proved to work.

our experience of this purgatory may depend on where you live. While a CDC committee sets recommendations for how to prioritize initially scarce doses, each state ultimately decides how to allocate the vaccines it receives. A person who qualifies as an essential worker in Illinois might not in Indiana. One city could end up opening vaccinations to the general public before its neighbor. This system is meant to be local and flexible, but that will necessarily mean a patchwork of policies that could come off as unfair or inconsistent.

“It is such a complicated and large logistical challenge that a lot of things will go wrong. A lot of things will not go to plan,” says Eric Toner, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. “The important thing is not to get hung up on that.” Hard trade-offs are ahead, as many groups have some claim to priority but they by definition cannot all be prioritized. Toner says not to lose sight of the ultimate goal: “Let’s just keep vaccinating people.”

The decisions still being made about how to prioritize vaccines will dramatically color individuals’ experiences over the next months. But ultimately getting out of purgatory will require reaching herd immunity, which is something we can only achieve collectively. Vaccines can protect individuals, but vaccination as a public-health strategy protects a community. Every person who gets vaccinated is a small step toward herd immunity, toward bringing down the amount of circulating virus. Eventually, we can all go back to schools and dinner parties and concerts.

I. Health-care workers and nursing-home residents and staff

Vaccines will do very little to change life for the average American in 2020. The very first Americans to receive COVID-19 vaccines will be health-care workers and residents of long-term-care facilities. These priorities, set by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices last week, are meant to preserve the health-care system and to save lives. People in long-term-care facilities account for many of the hospitalizations and roughly 40 percent of U.S. COVID-19 deaths, according to data from the COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic , even though only a small fraction of the country’s population—less than 1 percent—lives in these facilities.

Because the first shipments of vaccines will not cover all 24 million people in these two groups, the CDC has recommended sub-prioritizations too. Hospital workers who are in contact with patients are first on the list—including janitorial and support staff. The CDC also asks hospitals to consider that people who have recovered from COVID-19 likely have some immunity, so they do not need to be vaccinated first, though they won’t be prevented from getting vaccinated when doses are available later. For long-term-care facilities, the CDC recommends putting skilled-nursing facilities, which have the sickest patients, before assisted-living facilities.

After vaccination begins, hospitals and nursing homes will not change overnight. Both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines require two doses, three and four weeks apart, respectively, and even then the vaccines take time to build immunity—the companies measured 95 percent protection from COVID-19 symptoms only after one or two weeks. That will be well into 2021 for even the first people vaccinated this year. (The first dose may offer some protection after 10 days, but that likely wouldn’t be as strong or as long-lasting as the full regimen.)

Scientists also do not yet have the data to confirm that the vaccines actually prevent people from spreading the coronavirus asymptomatically in addition to preventing COVID-19 symptoms. This is likely, but data on this won’t be available until early next year. For now, a vaccine can clearly offer some protection to the recipient—but that person can’t be fully confident about not spreading the disease to others. A nurse might feel safer at work but still worry about bringing the virus home to their family.

Moreover, “even with a vaccine that is 95 percent effective, you don’t know if you are in the 5 percent,” Marci Drees, the infection-prevention officer at ChristianaCare and a representative on the CDC advisory committee, points out. Health-care workers who come in contact with COVID-19 patients will continue to need full personal protection equipment. Drees says she doesn’t anticipate any changes in PPE or quarantine-after-exposure policies in the near term.

Slowly, though, small corners of the world could start to change. In nursing homes where every staff member and resident gets vaccinated—essentially reaching building-wide herd immunity—some restrictions could be loosened. Residents could increase their very limited socializing with one another. Jason Belden, the director of emergency preparedness for the California Association of Health Facilities, says the buildings might eventually open to some visitors, but symptom checks and masking will continue. With everyone inside vaccinated, the risk from unknowingly letting in a visitor who is infected is diminished, but not zero.

States, hospitals, and nursing homes are still dealing with a lot of unknowns right now though. For one, Operation Warp Speed keeps changing the number of doses that will be initially available to each state. Kris Ehresmann, the director of the Minnesota health department’s infectious-disease division, told me that the numbers have changed so many times just in the past week, “I had this slide that I showed to the governor on Thursday. Then when I gave an update Monday, I used the same slide and had to cross things out. And I gave an update [Wednesday], and I crossed even more things out.”

States also have no sense of how regularly shipments will come, so they are unable to plan beyond the first few weeks. Hospitals, for example, might be able to vaccinate only a quarter of their staff in the first wave. Without knowing more, they will then be unable to reassure their staff about when the rest will get the shots—will it be in one or four or eight weeks? This uncertainty is one of the biggest challenges for hospitals right now, says Azra Behlim, a senior director at the health-care-services firm Vizient. “There’s a little bit more panic when I don’t know when I’ll be getting anything else.”

The inclusion of nursing-home residents in the first priority group by the CDC advisory committee also came as a bit of a surprise to states, which did not expect it when they drew up vaccine plans earlier this year. The federal government has contracted with CVS and Walgreens to help vaccinate nursing-home residents, but this division of responsibility between the federal and state levels has also introduced confusion. Ehresmann says she’s been told to reserve some number of her state’s 183,000 initial doses for nursing homes, even though the nursing-home vaccination program won’t be ready to start for a few more weeks. In California, Belden says, facilities in the association are still waiting to find out which ones will get how many doses when. “All of our members are reaching out every day. Am I going to be first? Am I going to be second? What’s it going to look like? None of those questions have been answered,” he told me. “But I do suspect we’ll get answers very soon.”

Pfizer and Moderna expect to have 35 million to 40 million doses of their vaccines ready by the end of the year, which is almost enough to cover hospitals and nursing homes at two doses per person. By early 2021, states will be getting ready for the next priority group.

II. Essential workers and adults at risk for COVID-19

In some ways, the very first group is actually the easiest to vaccinate. Health-care workers and residents of long-term-care facilities are relatively well-defined groups, and they are already concentrated in hospitals and nursing homes. “The real test will be what comes after that,” says Saad Omer, a vaccinologist and the director of the Yale Institute for Global Health. It only gets harder from here.

The first hard choice is a stark one: Who should come next, essential workers, or adults over 65 or with comorbidities? The question boils down to which strategy to prioritize, Omer says: reducing transmission out in the community, by vaccinating essential workers interfacing with the public, or reducing deaths, by vaccinating the people most at risk of dying of COVID-19.

The CDC advisory committee has indicated that it will recommend essential workers next, though the National Academies and the World Health Organization have recommended the opposite. None of this guidance is binding. The decision is ultimately up to the states, though they have historically followed the CDC.

Essential workers are also a nebulous category, and again, states get to set their own definitions. “There are an awful lot of interest groups that are lobbying states and lobbying feds to get their members or their constituents vaccinated sooner,” Toner told me. Should bank tellers count as essential workers? Teachers? Exterminators? And how should states prioritize different groups of essential workers? One study found that 70 percent of American workers can be defined as essential workers and 42 percent as frontline workers who directly interact with the public.

The decision to prioritize essential workers also has to do with reaching working-class Black and Latino communities that have been disproportionately hit by the coronavirus. But these are the same communities that may be hardest to reach—because of distrust in the government and language barriers. As part of their vaccine planning, state health departments are planning to connect with churches, nonprofit groups, and other leaders in those communities. Without this effort, vaccines will go only to people who come asking for it. “The people who are capable of advocating for themselves in these situations are sometimes people who are less in need of the services than those who are not advocating for themselves,” says Kelly Moore, an associate director of the Immunization Action Coalition. These communities might take longer to reach, which means the overall vaccination might proceed a bit slower. There can be tension, Toner adds, between vaccinating as many people as quickly as possible and actually reaching priority groups.

States and the CDC are still working out who will qualify as adults at high risk for COVID-19. Again, there’s a trade-off: Requiring proof will make getting the vaccines out harder, but forgoing it might mean someone who doesn’t strictly qualify gets a vaccine. “I don’t think we should get mired in documentation,” Toner said. “I don’t feel like they should have to show their medical record to prove that they’re diabetic. Or if they say they’re 65, but they’re only really 64, I wouldn’t have them bring a birth certificate. I think to some extent, we would have to trust people.”

III. The general public

Five months into the future, the plans get even fuzzier.

When vaccines become available to the general public depends on a few unknowns. First, how many other vaccine candidates, like AstraZeneca’s and Johnson & Johnson’s, will actually also get authorized? These companies have already ramped up manufacturing, so doses can be ready to go as soon as the FDA gives the green light. Second, will they run into manufacturing delays? The mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna rely on a new technology that has never been used in an approved vaccine, let alone produced at the scale needed now. During manufacturing of the more routine H1N1 swine-flu vaccine during the 2009 pandemic, the U.S. ran out of “fill and finish” facilities that package bulk vaccines into vials. The government set up a program to prevent this bottleneck in the future, but other unforeseen snags may come up.

The last stage of purgatory will be getting vaccines to the general public. Some parts of the country may allow everyone to get the vaccine sooner than others. In 2009, says Moore, who was running Tennessee’s immunizations program at the time, demand for the swine-flu vaccine in priority groups varied across the state. Some vaccine providers had doses for priority groups sitting unused, while members of the general public were asking about shots. Moore let those providers begin giving the vaccine to anyone who asked. This dynamic is very likely to play out between cities and between states with the COVID-19 vaccine, where doses are currently being allocated by census population but demand may vary.

This decision is tough because it’s likely to be criticized either way. “Visualize the frustration … if Georgia and Tennessee and Alabama all have different groups being allowed to be vaccinated at different times. But if you don’t, if you try to make everyone in the whole country do these groups in lockstep, then you can imagine that that also is terribly unfair,” Moore says, if “there are lots of willing people who could be protected, and vaccine is being withheld.”

Vaccine hesitancy is, of course, also a more general concern across the country. But Americans’ willingness to take a COVID-19 vaccine has risen as data on the vaccines’ efficacy have come out, and experts expect it to keep rising if early vaccination goes well. Many people have said they are more comfortable waiting a few months to get the vaccine, which is in effect what will happen.

Eventually, our social lives can start getting back to normal. It won’t happen in a moment, but stepwise, in small ways and then larger ones. Omer says small gatherings like dinner parties and game nights might be safe if everyone in the group is vaccinated. School reopenings and mass gatherings will likely happen only when widespread vaccination—along with masks and social distancing through the winter and spring—pushes COVID-19 rates to low levels.

Public-health experts stress that vaccines work in tandem with other measures: The start of a vaccination campaign cannot be an excuse to abandon the measures that are working right now. Moore likens vaccines to another slice on a pile of Swiss cheese, where each slice is an intervention that is by itself imperfect (masks, social distancing, even vaccines) but they drastically reduce risk when stacked together. Rochelle Walensky, President-elect Joe Biden’s pick for CDC director, made this analogy on Twitter: “If I have a cup of water, I can put out a stove fire. But I can’t put out a forest fire, even if that water is 100% potent. That’s why everyone must wear a mask. As a nation, we’ll recover faster if you give the vaccine less work to do when it’s ready.”

There will likely be many frustrating and imperfect things about the vaccine rollout in the next few months. But the goal is to get the country—and, really, the world—back to normal, and that happens not when you as an individual are vaccinated but when enough people all over are vaccinated. It might take longer than we like, but we get there together.

Santa is on the naughty list in Georgia.